Diese vermutlich neue Vogelart wurde bereits 2015 entdeckt (zu dieser Zeit aber nicht als neu erkannt), so dass die offizielle Entdeckung als neue Art tatsächlich erst im Jahr 2024 stattfand. [1]

Der El Dorado Ameisenpitta lebt im El Dorado Nature Reserve in der Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta im Norden Kolumbiens, eine Region in der sehr viele endemische Vogelformen beheimatet sind.

Ursprünglich wurden die Vögel als Schuppenbauch-Ameisenpittas (Grallaria squamigera Prévost & Des Murs) identifiziert; neuerdings geht man jedoch davon aus, dass sie eine eigenständige Art darstellen könnten, vor allem aufgrund ihrer Lautäußerungen, die offenbar deutlich anders klingen als die des Schuppenbauch-Ameisenpittas.

Noch ist nicht restlos geklärt, ob es sich tatsächlich um eine neue Art oder Unterart handelt, und endgültige Klarheit wird sicher erst durch DNA-Untersuchungen zu schaffen sein, es ist jedoch bereits klar, dass die Familie der Ameisenpittas tatsächlich weitaus artenreicher ist als zuvor gedacht. [2]

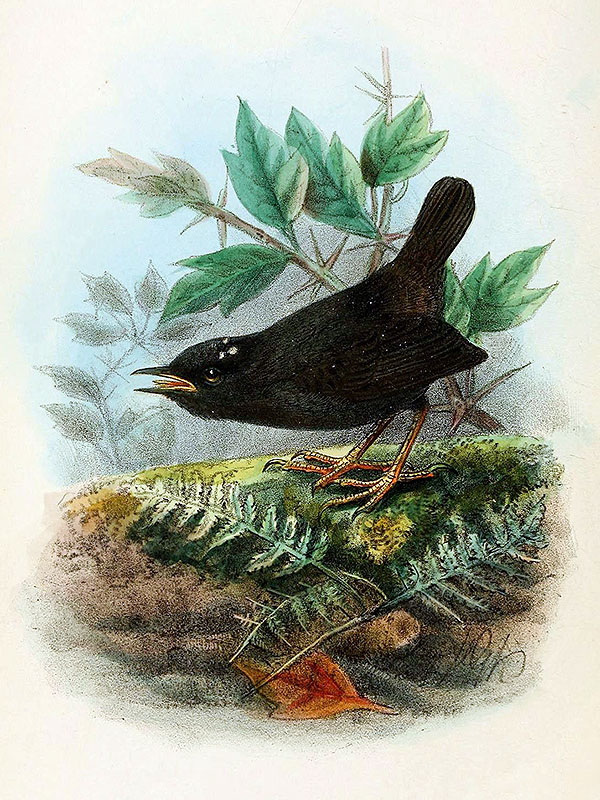

Photo: Fundacion ProAves

https://www.inaturalist.org/people/fundacion_proaves

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Photo: Norma Malinowski

https://www.inaturalist.org/people/bogwalker

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

*********************

Quellen:

[1] Sophie A. H. Osborn; Chad V. Olson: New record and known-range extension of Undulated Antpitta (Grallaria squamigera) in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta of Colombia. Boletín SAO 24(1&2): 9-12. 2015

[2] Morton L. Isler; R. Terry Chesser; Mark B. Robbins; Andrés M. Cuervo; Carlos Daniel Cadena; Peter A. Hosner: Taxonomic evaluation of the Grallaria rufula (Rufous Antpitta) somplex (Aves: Passeriformes: Grallariidae) distinguishes sixteen species. Zootaxa 4817(1): 1-74. 2020

*********************

bearbeitet: 18.04.2024