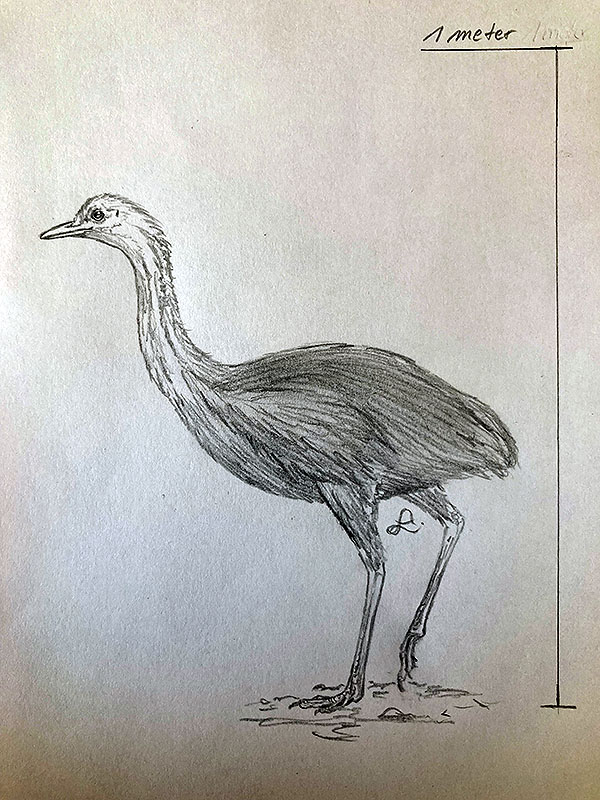

Riesenkauz (Strix sp.)

Diese rätselhafte Form ist nur anhand eines einzigen Fossils (USNM 214769) bekannt, einer Unterkiefersymphyse (Symphysis mandibulae) also quasi einem Unterschnabel, der sich einer Eulenart zuordnen lässt.

Das Fossil ähnelt am ehesten dem entsprechenden Knochen in Eulen der Gattung Strix, stammt aber von einer sehr viel größeren Art, viel größer als selbst die größte Art dieser Gattung, dem Bartkauz (Strix nebulosa Forster) und auch größer als jede andere lebende Eulenart; der Vogel mag zu Lebzeiten eine Gesamtlänge von etwas über 1 m erreicht haben! [1]

***

Die ersten Menschen, die im Oberen Pleistozän nach Nordamerika einwanderten, sind sehr wahrscheinlich Augenzeugen dieser riesigen Eulenart geworden. Und tatsächlich existieren Überlieferungen diverser Gruppen nordamerikanischen Unreinwohner, die von riesigen Eulen berichten, die sehr gefährlich gewesen sein- und sogar Jagd auf Kinder gemacht haben sollen.

*********************

Quelle:

[1] Storrs L. Olson: A very large enigmatic owl (Aves: Strigidae) from the Late Pleistocene at Ladds, Georgia. H. H. Genoways & M. R. Dawson: Contributions in Quaternary vertebrate paleontology: A volume in memorial to John E. Guilday. Carnegie Museum of Natural History Special Publication 8: 44-46. 1984

*********************

bearbeitet: 23.04.2025

Category Archives: Vögel

Grünracke

Grünracke (kein wissenschaftlicher Name)

Diese Form, die von irgendwo in Indien stammen soll, ist nur anhand der Beschreibung und der dazugehörigen Darstellung von François Le Vaillant aus dem Jahr 1806 bekannt; die Beschreibung lässt einige Fragen offen und erscheint nicht hundertprozentig mit der Abbildung übereinzustimmen.

“Voici encore une espèce nouvelle, qui paroît se rapprocher beaucoup du rollier vulgaire, mais dont il diffère cependant assez pour former une espèce distincte et séparée. Nous ne connoissons pas le pays natal de cet oiseau , du moins le canton de l’Inde d’où il a été importé en Europe par M. Poivre, ….

Ce rollier, que nous appelons verd, parceque le verd est en effet la couleur dominante de son plumage, a tous les caractères et toutes les formes du rollier vulgaire, dont nous donnons la description dans l’article suivant; mais il est un peu moins fort de taille que lui, comme on le verra en comparant les figures de grandeur naturelle que nous donnons de l’un et de l’autre: il a les plumes du front jusqu’aux yeux, ainsi que celles qui avoisinent la base du bec et la gorge, d’un blanc roussâtre: la tête, le cou, le haut du dos, toutes les plumes scapulaircs, les plumes alaires les plus proches du corps, et généralement toutes leurs couvertures supérieures sont d’un verd aiguë-marine: toutes les plumes du dessous du corps, depuis le blanc roussâtre de la gorge jusqu’au basventre, sont aussi verd aigue-marine, mais d’un ton plus clair, et qui, prenant une nuance blanche vers le bas-ventre , devient enfin d’un blanc légèrement teint du même verd sur les couvertures du dessous de la queue: les six premières grandes pennes alaires sont d’un beau bleu violâtre; les suivantes sont de plus légèrement bordées de verd à leurs pointes: les plumes du croupion et les couvertures du dessus de la queue sont d’un verd bleuâtre, ainsi que les deux plumes intermédiaires de celle-ci, bleues par-tout ailleurs tant en-dessus qu’en-dessous, où ce bleu est cependant un peu plus clair: le bec est noir, et les pieds sont roux.” [1]

Übersetzung:

“Hier ist eine weitere neue Art, die der Blauracke sehr nahe zu sein scheint, von der sie sich aber dennoch so weit unterscheidet, dass sie eine eigene und eigenständige Art bildet. Wir kennen das Heimatland dieses Vogels nicht, zumindest nicht den Kanton in Indien, von wo aus er von Herrn Poivre, … importiert wurde.

Diese Racke, die wir Grün nennen, weil Grün tatsächlich die vorherrschende Farbe ihres Gefieders ist, hat alle Charaktere und alle Formen der gewöhnlichen Racke [Blauracke (Coracias garrulus L.)], die wir im folgenden Artikel beschreiben; aber sie ist etwas kleiner als sie, wie wir sehen werden, wenn wir die natürlichen Größenangaben vergleichen, die wir von beiden geben: die Federn von der Stirn bis zu den Augen sowie die, die die Basis des Schnabels umgeben, sind rötlich weiß: der Kopf, der Hals, der obere Rücken, alle Schulterfedern, die dem Körper am nächsten liegenden Flügelfedern und im Allgemeinen alle ihre oberen Bedeckungen sind von kräftigem Aquamaringrün: alle Federn auf der Unterseite des Körpers, vom rötlichen Weiß der Kehle bis zum Unterbauch, sind ebenfalls aquamaringrün, jedoch von einem helleren Ton, und nehmen zum Unterbauch hin einen weißen Farbton an und werden schließlich weiß, leicht mit demselben Grün gefärbt auf den Decken der Schwanzunterseite: die ersten sechs großen Flügelfedern sind von einem wunderschönen Purpurblau; die folgenden sind an ihren Spitzen heller mit Grün umrandet: die Federn des Bürzels und die Federn an der Oberseite des Schwanzes sind von bläulichem Grün, die beiden Mittelfedern desselben sind überall blau, sonst beide oben als unten, wo dieses Blau allerdings etwas heller ist: Der Schnabel ist schwarz und die Füße sind rot. “

(not in copyright)

Es handelt sich hierbei ziemlich wahrscheinlich um eine der vielen künstlichen Chimären, aus den Einzelteilen verschiedener Vogelarten zusammengebauten Stopfpräparaten, wie sie im frühen 19.Jahrhundert in vielen Sammlungen zu finden waren – je absonderlicher diese ausfielen umso höher waren die Preise zu denen geneigte Sammler sie zu kaufen tatsächlich bereit waren.

*********************

Quelle:

[1] François Le Vaillant: Histoire naturelle des oiseaux de paradis et des rolliers: suivie de celle des toucans et des barbus. Vol. 1. Paris, chez Denné le jeune, Libraire, rue Vivienne, N°, 10. & chez Perlet, Libraire, rue de Tournon 1806

*********************

bearbeitet: 23.04.2024

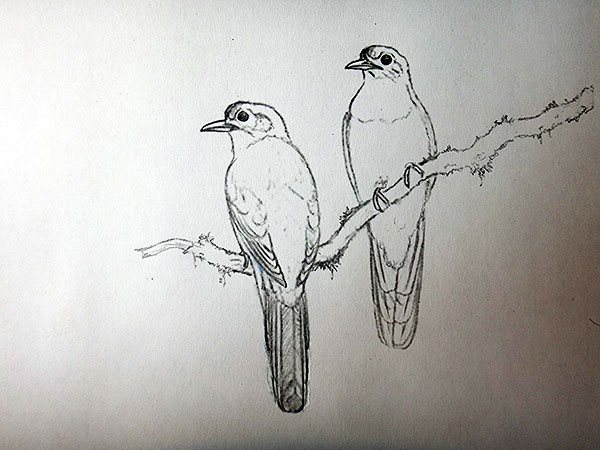

Dombeys Motmot

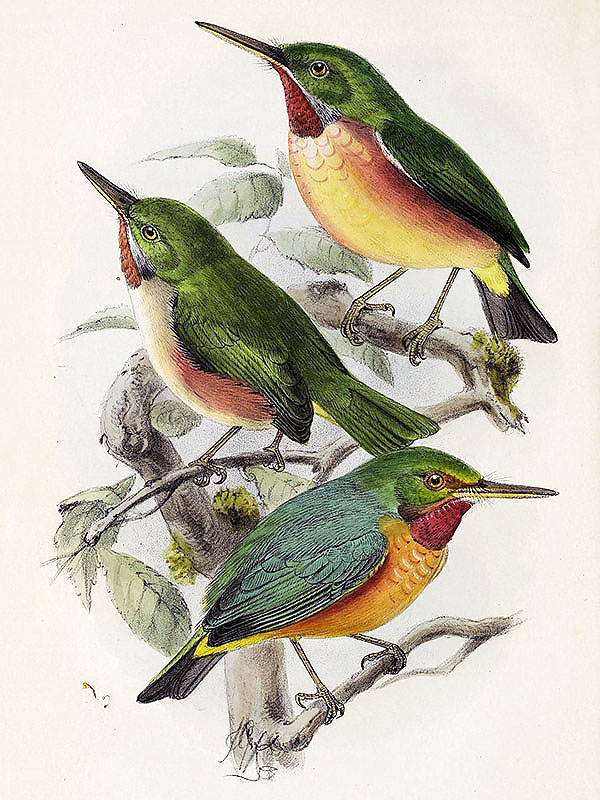

Dombeys Motmot (Baryphthengus dombeyi (Lesson))

Diese kaum bekannte Form ist nur anhand der Beschreibung (und Darstellung) von François Le Vaillant aus dem Jahr 1806 bekannt, die offenbar auf zwei Exemplaren beruht, die nicht mehr existieren; diese Beschreibung ist äußerst langatmig, daher werde ich sie hier nicht vollständig wiedergeben.

Der Vogel soll aus Peru stammen und dort in der Umgebung der heutigen Hauptstadt Lima vorgekommen sein.

“Nous n’étendrons pas davantage la description du momot dombé, parceque la figure exacte que nous en avons donnée mettra le lecteur qui le comparera à celui de l’espèce précédente, à même de saisir les rapports et les différences qui existent entre eux. Le houtou se trouve à la Guyane, et le momot dombé habite les forêts des environs de Lima, où le voyageur que j’ai nommé m’a assuré qu’il étoit très commun, et qu’il n’avoit remarqué aucune différence entre beaucoup d’individus qu’il avoit vus de l’espèce et les deux qu’il avoit rapportés, dont l’un fut déposé avec plusieurs autres beaux oiseaux du Pérou au cabinet du roi. Il est fâcheux que cet individu ait été entièrement détruit par les fumigations de soufre et les insectes: quant à l’autre nous ne savons ce qu’il est devenu.” [1]

Übersetzung:

“Wir werden die Beschreibung des Dombeys Motmots nicht weiter ausdehnen, da die genaue Abbildung, die wir wiedergegeben haben, den Leser, der sie mit denen der vorhergehenden Arten vergleicht, in die Lage versetzen wird, die Beziehungen und Unterschiede zwischen ihnen zu verstehen. Der Houtou [Braunscheitelmotmot (Momotus mexicanus Swainson)] kommt in Guyana vor, und Dombeys Motmot bewohnt die Wälder der Umgebung von Lima, wo der Reisende, den ich nannte, mir versicherte, dass er sehr häufig sei und dass er zwischen vielen Individuen, die er gesehen hatte, keinen Unterschied bemerkt habe und von den beiden, die er zurückgebracht hatte, einer zusammen mit mehreren anderen schönen Vögeln Perus im Kabinett des Königs deponiert wurde. Es ist bedauerlich, dass dieses Individuum durch die Begasung mit Schwefel und durch Insekten vollständig zerstört wurde; was den anderen betrifft, wissen wir nicht, was daraus geworden ist.“

(not in copyright)

*********************

Quellen:

[1] François Le Vaillant: Histoire naturelle des oiseaux de paradis et des rolliers: suivie de celle des toucans et des barbus. Vol. 1. Paris, chez Denné le jeune, Libraire, rue Vivienne, N°, 10. & chez Perlet, Libraire, rue de Tournon 1806

[2] Julian P. Hume: Extinct Birds. Bloomsbury Natural History; 2nd edition 2017

*********************

bearbeitet: 23.04.2024

Bensbachs Paradiesvogel

Bensbachs Paradiesvogel (Janthothorax bensbachi Büttikofer)

Diese Form wurde 1895 als neue Art beschrieben und ist bis heute nur anhand eines einzigen Exemplars bekannt, das in den Arfak-Bergen im Nordosten der Vogelkop-Halbinsel im Westen Neuguineas gefunden wurde.

Tatsächlich handelt es sich hierbei um einen Hybrid aus zwei sehr gut bekannten Paradiesvogelarten, nämlich dem Kleinen Paradiesvogel (Paradisaea minor Shaw) und dem Prachtparadiesvogel (Ptiloris magnificus(Viellot)).

(public domain)

*********************

Quellen:

[1] Errol Fuller: The Lost Birds of Paradise. Airlife 1996

[2] Clifford B. Frith; Bruce M. Beehler: The Birds of Paradise: Paradisaeidae. Oxford University Press 1998

*********************

bearbeitet: 23.04.2024

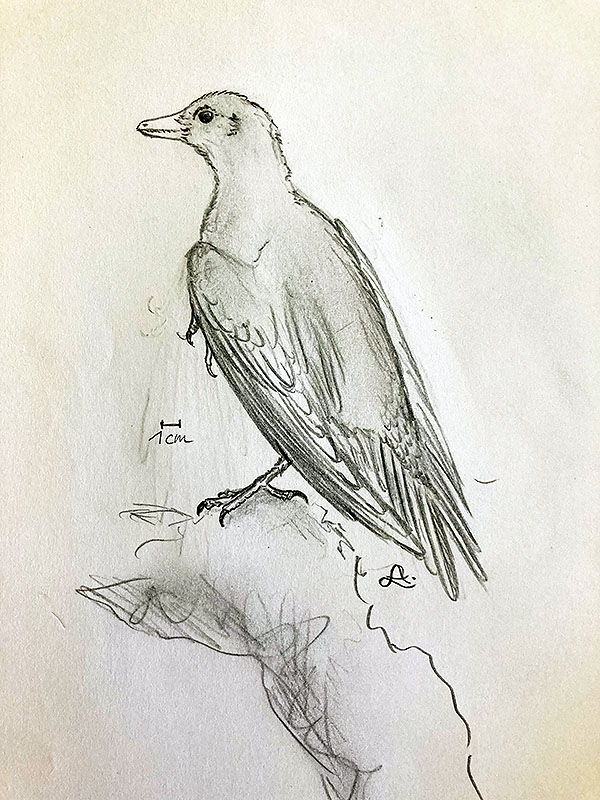

Drüsentaube

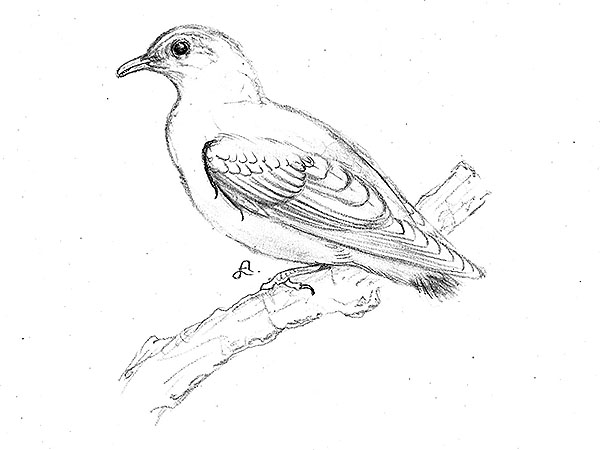

Drüsentaube (Columba carunculata Temminck)

Dies ist eine weitere von zahlreichen mysteriösen Vogelarten, die nur anhand von zeitgenössischen Beschreibungen und den dazugehörigen Darstellungen bekannt sind.

(public domain)

Die Originalbeschreibung stammt aus dem Jahr 1809 und ist mir nicht zugänglich, daher greife ich auf eine Beschreibung aus dem Jahr 1839 zurück, die sogar in deutscher Sprache verfasst wurde.:

“Von allen bis jetzt bekannten Tauben verbindet sich nach Temminck keine so enge wie diese mit den eigentlichen Hühnern, sowohl in der äußeren Erscheinung als in Gewohnheiten und Lebensweise, und auffallend dahin deutend ist gleich beim ersten Anblick das fleischige, drüsenartige Gehänge, wie wir solches and unserem Haushahn sehen. Die Drüsentaube ist wieder in Südafrika heimisch; sie wurde von Le Vaillant zuerst in der Gegend von Numaqua [Namibia] entdeckt, und folgenden näheren Bericht hat dieser thätige, gelehrte Naturforscher darüber in seinem schönen Werke: “Ueber die afrikanischen Vögel” ertheilt.

“Ihr Zusammengehören mit den Tauben … erkennt man zuerst an der Form des Schnabels, der genau mit diesen übereinstimmt, dann in den Eigenschaften und der Lage des Gefieders; sehr verschieden ist sie aber durch den rothen, nackten, fleischigen Auswuchs am Halse, dann durch die längeren Füße, einen runden plumpen Leib, durch das abhängige Tragen des Schwanzes, ungefähr wie beim Repphuhne, und endlich durch ihre mehr gerundeten Flügel, alles sonstige Kennzeichen der Hühnerarten, so daß sie am besten zwischen diesen und den Tauben zur Verbindung Beider steht. Sie baut ihr Nest in leichte Gruben auf der Erde aus dünnen Zweigen und dürren Halmen; das Weibchen legt sechs bis acht röthlich weiße Eier, die wechselnd von ihm und dem Männchen gebrütet werden. Die Jungen haben nach dem Auskriechen eine Bekleidung von röthlich grauem Flaume, laufen sogleich den Eltern nach, die sie fortdauernd durch einen sonderbaren Ruf zusammenhalten und mit ausgebreiteten Flügeln vor der kalten Nachtluft schützen. Ihre erste Nahrung besteht aus Ameiseneiern, kleinen Insecten und Würmern, welche von den Eltern ausgesucht und ihnen überlassen werden. Bei zunehmender Größe müssen sie selbst für sich sorgen, dann sind ihnen Getreide, Samenkörner, Beeren und Insecten willkommen. Sie bleiben, wie die Repphühner, in Flügen beisammen und trennen sich nur paarweise um die Brütezeit.”

In der Größe gleicht die Drüsentaube unserer gewöhnlichen Turteltaube, nur ist der Rumpf dicker und runder. Die Basis des Schnabels und der Vorderkopf werden von einer nackten, lebhaft rothen Haut überzogen, und am Halse hängt eine gleichfarbige Substanz, die sich zu beiden Seiten gegen die Ohren zieht. Kopf, Hals und Brust sind purpurgrau, Mantel, Achseln und Flügeldecken bleichgrau die Federn weiß gesäumt. Der Bauch, der hintere und Ober- und Untertheil der Schwanzfedern, so wie die Seiten unter den Flügeln, sind rein weiß. Der Schwanz kurz, abgerundet, die Federn tief rothbraun, mit Ausnahme der ersten Feder auf jeder Seite, deren äußere Fahne weiß ist. Der Schnabel zeigt sich an der Wurzel röthlich, gegen die Spitze schwarz. Die Füße sind purpurroth, mit sechseckigen Schuppen. Die Iris hat einen doppelten, inwendig gelben, auswendig rothen Kreis. Das Weibchen gleicht dem Männchen in der Lage des Gefieders, aber die Färbung desselben ist trüber und der Hals nicht, wie dort, behängt.” [1]

Interessant sind die Hinweise auf die Küken der ‘Art’, die hier als Nestflüchter beschrieben werden, welche gleich nach dem Schlüpfen herumlaufen und von den Erwachsenen mit Insektennahrung versorgt werden – tatsächlich sind sämtliche Taubenarten Nesthocker und werden obendrein vom Weibchen mit so genannter Kropfmilch gefüttert ….

(public domain)

Die Drüsentaube gilt heute als eine der vielen frei erfundenen Vogelarten, die vor allem im frühen- bis mittleren 19. Jahrhundert in der Literatur sowie in Sammlungen seltener (aus Einzelteilen diverser Vögel zusammengebastelter) Vogelpräparate auftauchen.:

“Columba Carunculata Temminck, 1809: 19, pl. 11 is not applicable, artefact.

The name was based on an artefact. Temminck (1809) referred to a single specimen in the collection of Levaillant.” [2]

Übersetzung:

“Columba Carunculata Temminck, 1809: 19, Taf. 11 ist nicht zuordenbar, Artefakt.

Der Name basierte auf einem Artefakt. Temminck (1809) verwies auf ein einziges Exemplar in der Sammlung von Levaillant.“

*********************

Quellen:

[1] Friedrich Treitschke: Naturgeschichte der Tauben, nach Prideaux Selby. Naturgeschichtliches Cabinet des Thierreiches VII. Pesth 1839

[2] Steven D. van der Mije; Pepijn Kamminga; René W. R. J. Dekker: Type specimens of non-passerines in Naturalis Biodiversity Center (Animalia, Aves). Zookeys 1155: 1-311. 2023

*********************

edited: 19.04.2024

Türkentaube

*********************

bearbeitet: 09.04.2024

Blue Tit

*********************

edited: 18.10.2023

Coal Tit

*********************

edited: 18.10.2023

European Jackdaw

*********************

edited: 18.10.2023

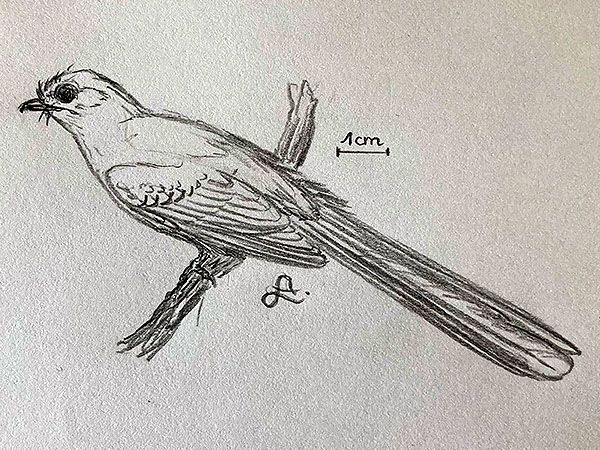

Birds unknown – the Spotted Wren-Babbler

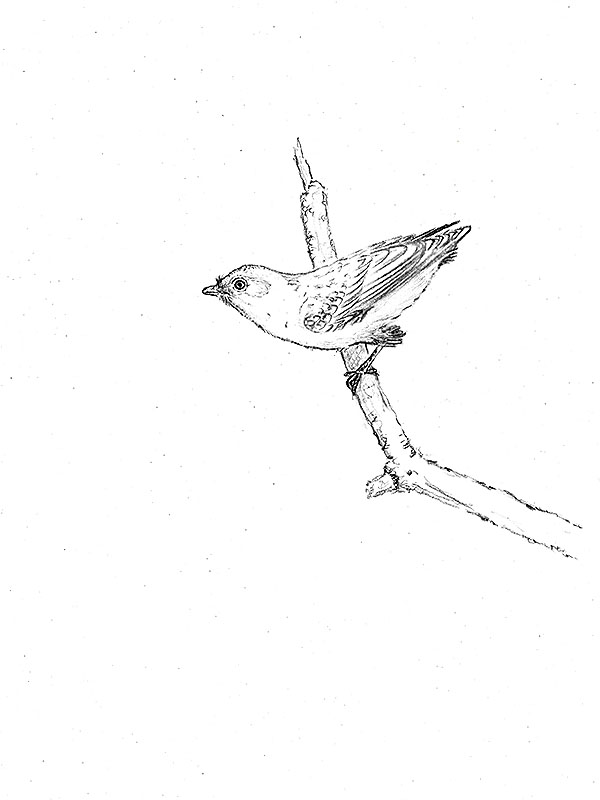

Spotted Wren-Babbler (Elachura formosa Walden)

***

The Spotted Wren-Babbler or Spotted Elachura (or just Elachura) is an approximately 10 cm long, inconspicuous bird that inhabits the understory of dense forests in South- and Southeast Asia.

The species was originally described as a wren, later assigned to the timalia family and finally placed in its own monotypic family because it does not appear to be related to any other bird species; however, it has similarly shaped foot soles as the waxwings (Bombycilidae) and goldcrests (Regulidae), which are also taxonomically quite isolated, but no further studies have been carried out on this yet. [1][2]

*********************

https://www.inaturalist.org/people/udayagashe

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

*********************

References:

[1] Per Alström; Daniel M. Hooper; Yang Liu; Urban Olsson; Dhananjai Mohan; Magnus Gelang; Hung Le Manh; Jian Zhao; Fumin Lei; Trevor D. Price: Discovery of a relict lineage and monotypic family of passerine birds. Biology Letters 10(3): 1-5. 2014

[2] Jon Fjeldså; Les Christidis; Per G. P. Ericson: The Largest Avian Radiation: The Evolution of Perching Birds, or the Order Passeriformes. Lynx Edicions 2020

*********************

edited: 09.10.2023

Birds unknown – the Grande Comore Blue Vanga

Grande Comore Blue Vanga (Cyanolanius comorensis ssp. bensoni Louette & Herremans)

***

This taxon, described in 1982, is thought to inhabit, or to have inhabited, the island of Grande Comore, Comoros in the Indian Ocean; it is, however, known from only a single somewhat doubtful specimen that was collected as late as 1981.

Here is an excerpt from the original description.:

“In bill length intermediate between C. m. madagascarinus and comorensis; total culmen 18.5 mm as against an average of 17.3 in both sexes of madagascarinus and 20.1 mm in both sexes of comorensis. Bill decidedly more robust than in madagascarinus, although not much longer. In plumage in all respects seemingly nearest to comorensis although there is no similar aged specimen of this race available.“

“Apart from the diagnosis of bensoni, the following is a fuller description of the holotype (not fully adult):- Upperparts lilac blue, crown somewhat darker, with a few bright blue (adult) feathers appearing on crown and mantle. Inner webs of inner secondaries blue, like outer webs (like comorensis, inner webs not black as in madagascarinus). Underparts white, a few buffish feathers on flanks. Black mask just starting to appear. Tail feathers with square tips, not pointed as in very young specimens of Cyanolanius, and with buffish fringes. Iris pale blue. Legs grey-blue. Bill with pale base to both mandibles, tips dark. One may conclude that bensoni agrees well with comorensis in plumage characteristics but has a definitely less robust bill, intermediate in size between the 2 other races. Some doubt may persist as to the bill size in the adult, but I have measurements from 4 immatures of madagascarinus (mounted) in RNL, certainly somewhat younger than the holotype of bensoni, averaging 17.1 (versus 17.3 in the adult, see above) showing that this possible difference is insignificant.”

***

This sole specimen may represent a stray from the nearby island of Mohéli, which is home to the nominate race of the Comoros Blue Vanga (Cyanolanius comorensis (Shelley)), or it may indeed constitute a member of a distinct endemic population. If there indeed ever was a population of Blue Vangas living on Grande Comore, it must now be extinct.

There is also another mystery – why are there no Blue Vangas to be found (at least today) on the islands of Anjouan and Mayotte which in fact lie between Mohéli and Madagascar?

*********************

Photo: RMCA, Tervuren

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

*********************

References:

[1] M. Louette; M. Herremans: The Blue Vanga Cyanolanius madagascarius on Grand Comoro. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club 102(4): 132-135.1982

*********************

edited: 04.10.2023

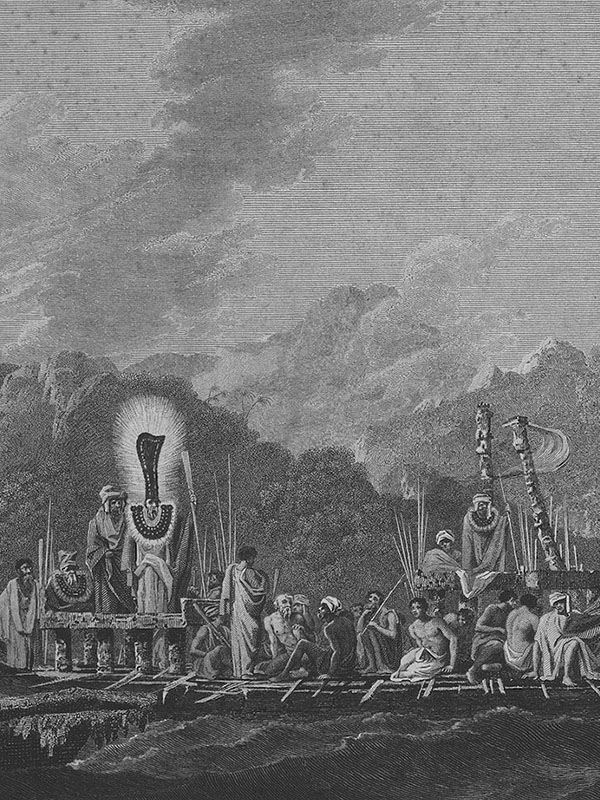

Mo’ora-‘ura and toroa – a red duck and a surf duck from Tahiti?

In ancient times, Tahitians believed that several of their Gods and other celestial beings would show themselves to the human eye in form of an animal, a so-called ata and Teuira Henry [see also here] lists some of them, among them also three kinds of ducks.:

“Red-feathered duck (mo‘ora-‘ura), ata of ‘Orovehi‘ura (‘Oro in his manifestation of Red-feather-covered).

Wild duck (mo‘ora-ōviri), ata of “sylvan elves.”

Surf duck (toroa), ata of Hau, god of peace.” [1][3]

The ‘Wild duck’, mentioned here, is the Pacific Black Duck (Anas superciliosa J. F. Gmelin) which is the only duck species known from French Polynesia at all, so what are the other two ‘ducks’?

“The most showy headdress worn officially by the king and princes and high chiefs was the taumi, a superb helmet made of clusters of crimson feathers of the moora ‘ura (red-feathered duck), set upon a light framework and covering the head like a bird, with a glossy terminal behind of outspreading red, black, and white feathers tastily mixed together.” [1][3]

A taumi, however, actually is a gorget decorated with feathers, a feathered helmet was called fau.:

“Henry gives a description of a headdress which has some characteristics of a fau, but which seems to be a mixture of remembered types, further confused by the use of the name taumi, which we know was a gorget:” [4]

The fau was also decorated with several of the elongated tail feathers of tropicbirds (as you can see in the depiction, in which they are from the White-tailed Tropicbird (Phaethon lepturus ssp. dorotheae Daudin)).

Depiction from: ‘William Hodges: The fleet of Otaheite assembled at Oparee, 1777’

(public domain)

*********************

A little update here:

A “surf duck” apparently is nothing but an albatross (Diomedea spp.), a bird that is well known to the Polynesians, even in the tropical parts of the region. [2]

*********************

References:

[1] Teuira Henry: Ancient Tahiti. Bishop Museum Bulletins 48: 1-651. 1928

[2] Kenneth P. Emory: Tuamotuan bird names. The Journal of the Polynesian Society 56(2): 188-196. 1947

[3] Douglas L. Oliver: Ancient Tahitian Society. The University Press of Hawai’i, Honolulu 1974

[4] Karen Stevenson; Steven Hooper: Tahitian fau – unveiling an enigma. Journal of the Polynesian Society 116(2): 181-212. 2007

*********************

edited: 31.07.2023

Did parakeets once inhabit the Tuamotu Islands?

Parakeets of the genus Cyanoramphus are known to once have existed in French Polynesia, namely on the Austral- and the Society Islands. Is it possible that one or more species of that genus once also have existed on the Tuamotu Archipelago?

Well, actually, it absolutely is, but there is yet no actual indication of it; or maybe there is one …:

In a count of Tuamotuan bird names from the 1940s the name petea is given as coming “from an informant in the western Tuamotus, who said it was like the petea of Tahiti.” [1] and that is probably the name of a parakeet. Maybe this informant just gave that name and told the author that it is given to a long-tailed bird that is also found on Tahiti, who knows?

Well, a short check informs us that petea or rather pete’a is indeed a Tahitian bird name but actually for the White-tailed Tropicbird (Phaethon lepturus ssp. dorotheae Mathews) which in fact is not a parakeet, unfortunately.

***

So, while the former occurrence of parakeets on at least some of the atolls and islands in the giant Tuamotuan Archipelago seems absolutely possible, we have yet no real proof of that … and probably never will.

But we can let our imagination run wild, why not?!

*********************

References:

[1] Kenneth P. Emory: Tuamotuan bird names. The Journal of the Polynesian Society 56(2): 188-196. 1947

*********************

edited: 07.07.2023

Acrocephalus sp. BMNH 1846.7.29.6

The British Museum of Natural History is apparently housing a reed-warbler specimen that is sister to the Leeward Islands Reed-Warbler (Acrocephalus musae (J. R. Forster)) , a now extinct species that occurred with two subspecies on the islands of Huahine and Ra’iatea in the leeward group of the Society Islands.

However, this single specimen appears not to be identical to either of the two known subspecies and was proposed to be classified as “A. musae subsp. (Leeward Islands), with uncertainty regarding the island and subspecies.” [1]; it might indeed represent another, third subspecies that had been collected from another island within the leeward group.

*********************

References:

[1] Alice Cibois; Jean-Claude Thibault; Eric Pasquet: Molecular and morphological analysis of Pacific reed warbler specimens of dubious origin, including Acrocephalus luscinius astrolabii. Bulletin of the British Ornithologist’s Club 131(1): 32-40. 2011

*********************

edited: 05.07.2023

Neuntöter

*********************

bearbeitet: 29.06.2023

Buchfink

*********************

bearbeitet: 29.06.2023

Mäusebussard

*********************

bearbeitet: 29.06.2023

Tafelenten

*********************

bearbeitet: 29.06.2023

Nilgans

*********************

bearbeitet: 29.06.2023

Höckerschwäne

*********************

bearbeitet: 29.06.2023

Hausspatzen

*********************

bearbeitet: 29.06.2023

Wiedehopf

*********************

bearbeitet: 29.06.2023

Kolkraben

*********************

bearbeitet: 29.06.2023

Kleiber

*********************

bearbeitet: 19.03.2023

Morsoravis sedilis Bertelli, Lindow, Dyke & Chiappe

*********************

bearbeitet: 08.03.2023

Sororavis solitarius Mayr & Kitchener

*********************

bearbeitet: 08.03.2023

Brevirostruavis macrohyoideus Li et al.

*********************

bearbeitet: 16.11.2022

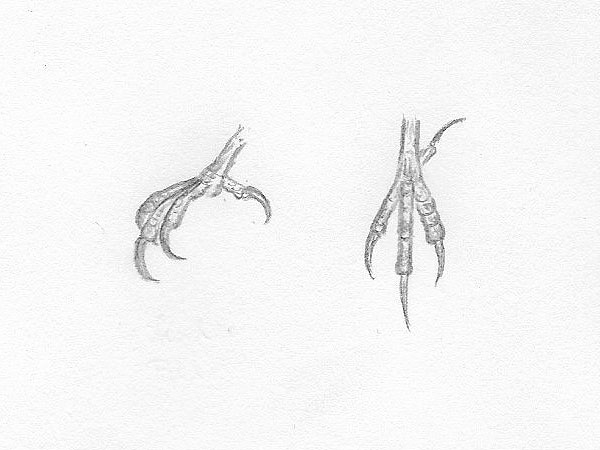

Seltsame Kreidezeit-Füße – Teil 2: DIP-V-15105a/b

DIP-V-15105a und DIP-V-15105b sind zwei Bernsteinfossilien, einmal ein fast vollständig erhaltener Fuß und zum anderen Teile eines Flügels, bzw. dessen Federn, beide gehören ziemlich wahrscheinlich zueinander.

DIP-V-15105a/b erreichte die Größe eines Kolibris, genauer gesagt eines winzigen Kolibris.

Der Fuß (es ist der rechte Fuß) ist interessanterweise bis fast zu den Zehen befiedert, wobei sich hier sogar zwei verschiedene Federformen finden, etwas längere, offenbar bräunlich gefärbte, dicht stehende Federn auf der Fußoberseite sowie vereinzelte, winzige borstenartige Federchen auf den eigentlichen Zehen selbst.

Dem Fußbau nach zu urteilen war dieser Vogel einem heutigen Baumläufer oder Kleiber vergleichbar, lebte also in den Wipfeln der Bäume und hielt sich bevorzugt an den größeren Ästen und den Stämmen auf wo er auf der Suche nach Insektenbeute schließlich mit dem Fuß in ausgetretenem Baumharz kleben blieb und so einen grausigen Tod fand.

*********************

Referenzen:

[1] Lida Xing; Ryan C. McKellar; Jingmai K. O’Connor; Ming Bai; Kuowei Tseng; Luis M. Chiappe: A fully feathered enantiornithine foot and wing fragment preserved in mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber. Scientific Reports 9(129): 1-9. 2019

leider habe ich gerade kein Gummibärchen zur Hand ….

*********************

bearbeitet: 15.11.2022

Farbtafel

*********************

bearbeitet: 03.11.2022

Hybridkrähe

*********************

bearbeitet: 02.10.2022

Feder

*********************

bearbeitet: 02.10.2022

Feder

*********************

bearbeitet: 24.09.2022

Feder

*********************

bearbeitet: 05.06.2022

Messelirrisor parvus Mayr

*********************

bearbeitet: 30.05.2022

Primozygodactylus major Mayr

*********************

bearbeitet: 27.05.2022

Eurofluvioviridavis robustipes Mayr

*********************

bearbeitet: 27.05.2022

Primozygodactylus eunjooae Mayr & Zelenkov

*********************

bearbeitet: 24.05.2022

“Zygodactylus” ochlurus Hieronymus, Waugh & Clarke

*********************

bearbeitet: 24.05.2022

Eremopezus eocaenus Andrews

*********************

edited: 23.05.2022

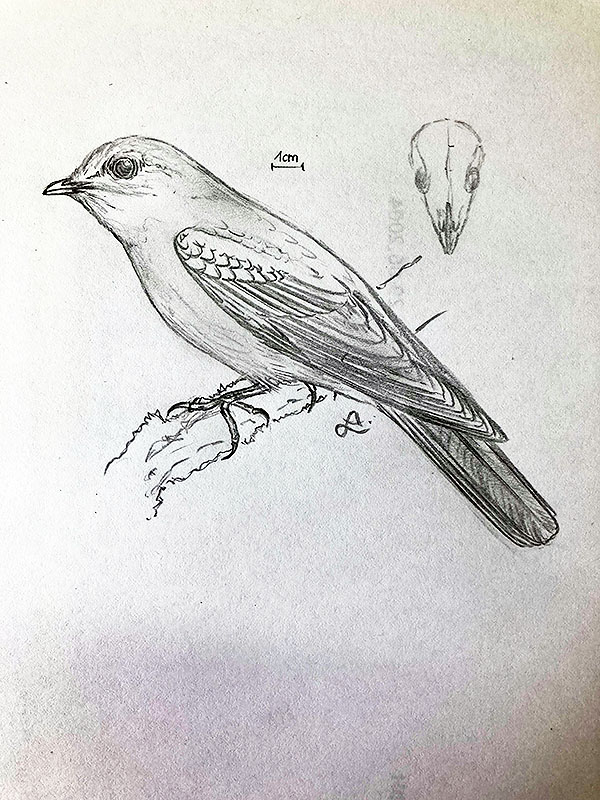

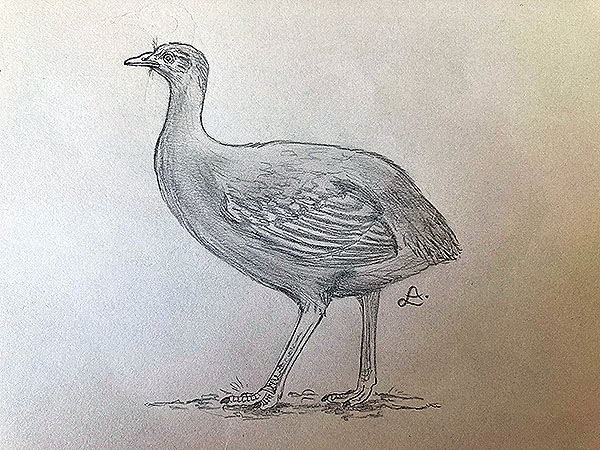

Remiornis heberti Lemoine

Beschrieben bereits 1881 aber bis heute nahezu unbekannt, ist diese Art, soweit mir bekannt, nur anhand von Bruchstücken des Schnabels sowie einiger Wirbel und eines Fußknochens bekannt.

Der Vogel war, laut einiger Autoren, zu Lebzeiten etwa so groß wie ein Emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae (Latham)) und mag ca. 55 kg gewogen haben [3]; ich persönlich komme beim Umrechnen aber nur auf eine Rückenhöhe von etwas über 70 cm.

Die Art ist bisher nur aus Frankreich bekannt und zwar aus Ablagerungen des Oberen Paläozän, also Schichten mit einem Alter von etwa 59 bis 56 Millionen Jahren, sie scheint außerdem mit keinem anderen Ratiten, lebend oder ausgestorben, näher verwandt gewesen zu sein.

*********************

*********************

Quellen:

[1] Victor Lemoine: Recherches sur les oiseaux fossiles des terrains tertiaires inférieurs des environs de Reims. Reims, Impr. F. Keller 1878-1881

[2] Eric Buffetaut; Delphine Angst: Stratigraphic distribution of large flightless birds in the Palaeogene of Europe and its palaeobiological and palaeogeographical implications. Earth-Science Reviews 138: 394-408. 2014

[3] Eric Buffetaut; Gaël de Ploëg: Giant birds from the uppermost Paleocene of Rivecourt (Oise, northern France). Boletim do Centro Português de Geo-História e Pré-História 2(1): 29-33. 2020

[4] Gerald Mayr: Paleogene Fossil Birds. 2nd ed. edition 2022

*********************

bearbeitet: 22.05.2022

Messelornis cristata Hesse

*********************

bearbeitet: 21.05.2022

Palaeotis weigelti Lambrecht

*********************

bearbeitet: 21.05.2022

Parargornis messelensis Mayr

*********************

bearbeitet: 17.05.2022

Landbirds of the Brazilian Atlantic islands

In the Atlantic Ocean are three groups of islands that are politically part of Brazil and about which little seems to be known: the Fernando de Noronha Archipelago and the Rocks of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, both located near the equator and Trindade & Martim Vaz near the southern 20th parallel.

Interestingly, as many as four land bird species are known from these archipelagos, of which at least three are truly native and endemic: the Noronha Olive Tyrant (Elaenia ridleyana Sharpe) (Tyrannidae), the extinct Noronha Rail (cf. Rallus sp.) (Rallidae), the Noronha Vireo (Vireo gracilirostris Sharpe) (Vireonidae) and the Noronha Eared Dove (Zenaida auriculata ssp. noronha Sharpe) (Columbidae), all native to the largest archipelago, Fernando de Noronha.

***

There are also two more or less hypothetical forms for the second largest archipelago, Trindade & Martim Vaz: a pigeon form mentioned only by one of the first visitors to Trindade island at the end of the 17th century:

“In 1698 Dr. Halley visited the island, and says he found nothing living but doves and land-crabs.” [1]

And, for the time being, purely hypothetical but very probable, a rail, also for this one island.

***

No serious excavation appears to have taken place on any of the islands, such excavation would almost certainly unearth other bird forms that are now extinct.

*********************

References:

[1] R. Davis: Real Soldiers of Fortune. Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York 1906

[2] Robert Cushman Murphy: The birdlife of Trinidad Islet. The Auk 32(3): 332-348. 1915

[3] S. L. Olson: Natural history of vertebrates on the Brazilian islands of the mid South Atlantic. National Geographic Society Research Reports 13: 481-492. 1981

[4] Ruy José Válka Alves; Nílber Gonçalves da Silva: Três Séculos de História Natural na Ilha da Trindade com Comentários Sobre Sua Conservação. Smashwords 2016

*********************

edited: 05.07.2023

Heckenbraunelle

*********************

bearbeitet: 10.04.2022

Federn …

*********************

bearbeitet: 10.04.2022

Zealandornis relictus Worthy et al.

Dieser Vogel lebte in Neuseeland vor 19 bis 16 Millionen Jahren, ist bisher aber nur anhand eines Knochenbruchstücks bekannt.

*********************

Quelle:

[1] Trevor H. Worthy; R. Paul Scofield; Steven W. Salisbury; Suzanne J. Hard; Vanesa L. De Pietri; Michael Archer: Two new neoavian taxa with contrasting palaeobiogeographical implications from the early Miocene St Bathans Fauna, New Zealand. Journal of Ornithology http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10336-022-01981-6. 2022

*********************

bearbeitet: 08.03.2022

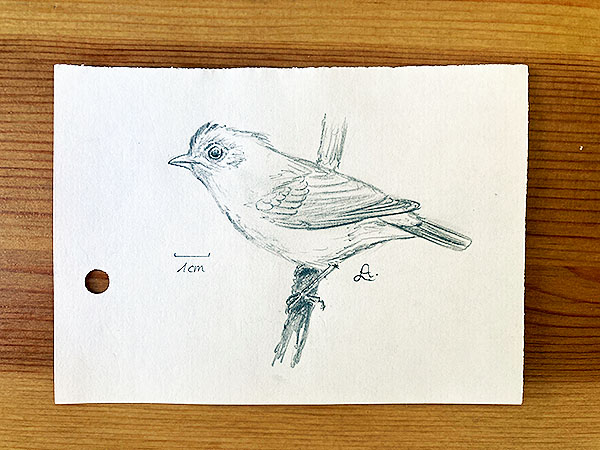

Zealandornithidae – eine neue fossile Familie neuseeländischer Vögel

Es ist eine einigermaßen bekannte Tatsache, dass Neuseeland auch heute noch einige Reliktpopulationen ansonsten längst ausgestorbener Lebensformen beherbergt, dies war aber bereits in der Vergangenheit so.

Die fossile Fauna der St Bathans-Fundstelle hat nun eine weitere solche Reliktlinie hervorgebracht, die Familie der “Zealandia-Vögel”, benannt anhand eines distalen Endstücks eines Humerus eines Vogels, der sich keiner bekannten Familie zuordnen lässt (Zealandornis relictus Worthy et al.). [1]

Dieser Vogel dürfte in etwa die Größe eines durchschnittlichen Finken erreicht haben und könnte mit den Mausvögeln verwandt gewesen sein, ohne dabei zu den Mausvögeln selbst zu gehören. Es ist möglich, dass seine Familie gondwanischen Ursprungs ist und in Neuseeland ihr letztes Refugium gefunden hatte, oder, wie etliche andere neuseeländische Vogelformen auch, ursprünglich aus Australien zugewandert ist. Wie so oft gilt auch hier, es sind weitere Funde notwendig um genauere Angaben zum Aussehen und zu den Verwandtschaftsverhältnissen dieser Art/Familie zu machen. [1]

Eine Rekonstruktion ist derzeit nicht wirklich möglich, bzw. wäre rein spekulativ.

*********************

Quelle:

[1] Trevor H. Worthy; R. Paul Scofield; Steven W. Salisbury; Suzanne J. Hard; Vanesa L. De Pietri; Michael Archer: Two new neoavian taxa with contrasting palaeobiogeographical implications from the early Miocene St Bathans Fauna, New Zealand. Journal of Ornithology http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10336-022-01981-6. 2022

*********************

bearbeitet: 08.03.2022

Fukuipteryx prima Imai et al.

Dieses Geschöpf lebte vor etwa 125 Millionen Jahren im heutigen Japan und war noch kein richtiger Vogel im eigentlichen Sinne.

*********************

bearbeitet: 23.03.2022

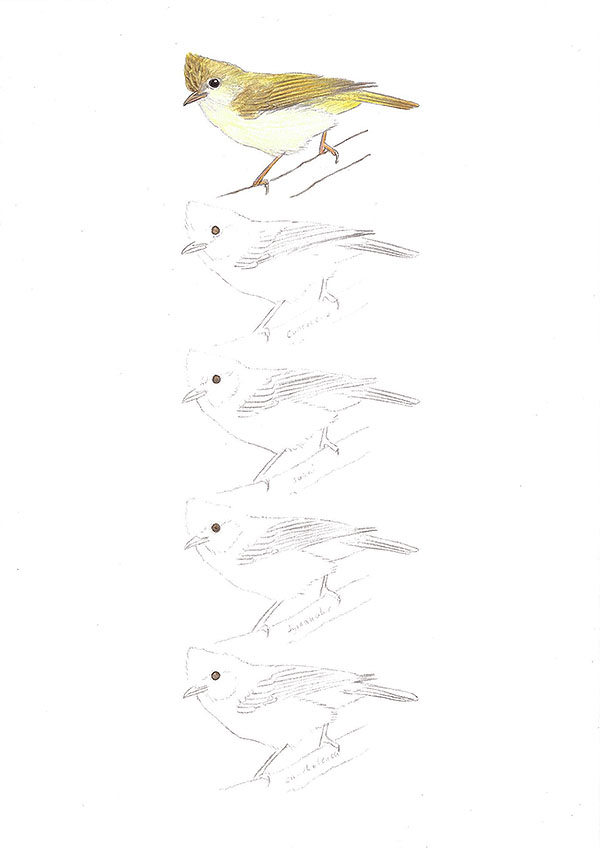

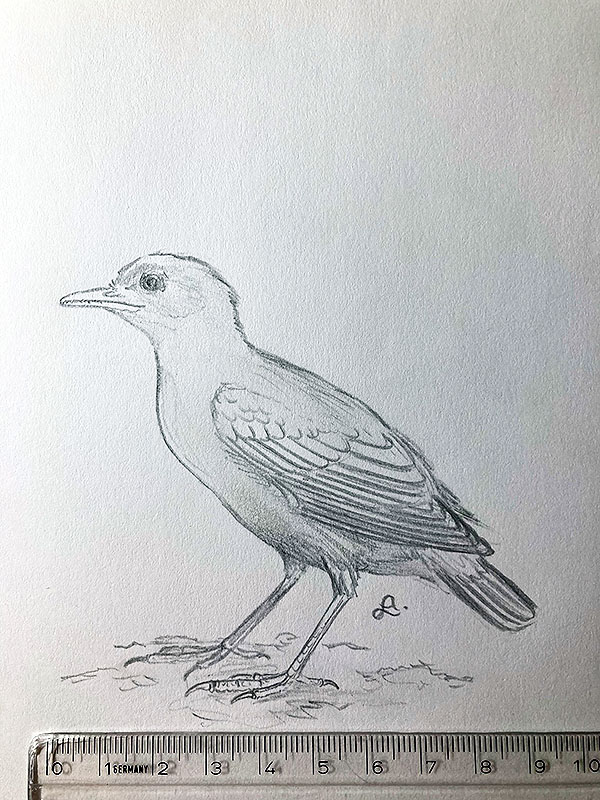

Passeriformer Vogel aus dem europäischen Miozän

Aus frühmiozänen (ca. 20 Millionen v.u.Z.) Ablagerungen in Europa, vor allem in Süddeutschland und Österreich sind zahlreiche passerine Vogelformen nachgewiesen, von denen nur wenig Material erhalten geblieben ist.

Leider sind die meisten davon wohl bis jetzt nicht weiter untersucht worden und demnach ist auch nicht näher bekannt, welchen Unterordnungen sie womöglich zuzuordnen sind (aus dem Oligozän, das dem Miozän vorangeht, sind aus Europa nur suboscine Sperlingsvögel (Tyranni) bekannt, die es hier heute überhaupt nicht mehr gibt), deswegen wäre es sehr interessant mehr über all diese fossilen Formen zu erfahren.

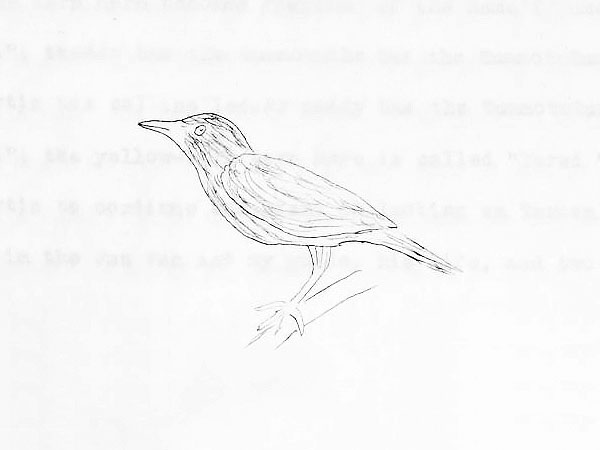

Der hier abgebildete Vogel ist nur als “Passerum gen. species A” benannt.

*********************

Quelle:

[1] Peter Ballmann: Die Vögel aus der altburdigalen Spaltenfüllung von Wintershof (West) bei Eichstätt in Bayern. Zitteliana 1: 5-60. 1969

*********************

bearbeitet: 23.03.2022

Messelastur gratulator Peters

*********************

bearbeitet: 06.03.2022

Serudaptus pohli Mayr

*********************

bearbeitet: 06.03.2022

Palaeotodus escampsiensis Mourer-Chauviré

Diese Art stammt aus dem oberen Eozän Europas und ist der älteste bislang bekannte Vertreter seiner Familie, die heute nur noch mit fünf Arten in der Karibik verbreitet ist.

Die eozäne Form erreichte eine Größe von nur etwa 10 cm und ähnelte somit wohl sehr den rezenten Todi-Arten. [1]

*********************

Quelle:

[1] Gerald Mayr; Norbert Micklich: New specimens of the avian taxa Eurotrochilus (Trochilidae) and Palaeotodus (Todidae) from the early Oligocene of Germany. Paläontologische Zeitschrift 84: 387-395. 2010

*********************

bearbeitet: 04.03.2022

Todus pulcherrimus Sharpe

Schöner Todi (Todus pulcherrimus Sharpe)

Von dieser ‘Art’, beschrieben im Jahr 1874, habe ich gestern überhaupt zum allerersten Mal gehört, sie ist offenbar nur anhand eines einzigen Exemplars bekannt, dessen Herkunft nicht gesichert zu sein scheint.:

“Hab. Jamaica [?]” [1]

Dieses eine Exemplar befindet sich offenbar im British Museum in London, Großbritannien und unterscheidet sich von allen bekannten Todi-Arten durch die eher bläulich als grün gefärbten Oberseite sowie die kräftig gefärbte Unterseite (siehe Darstellung).

***

Bei diesem mysteriösen Vogel soll es sich aber um einen aberrant gefärbten Breitschnabeltodi (Todus subulatus Gray) handeln, einer Art, die von der Insel Hispaniola stammt.

*********************

Darstellung aus: ‘R. Bowdler Sharpe: On the genus Todus. The Ibis 3(4): 344-355. 1874’

(public domain)

*********************

Quelle:

[1] R. Bowdler Sharpe: On the genus Todus. The Ibis 3(4): 344-355. 1874

*********************

bearbeitet: 18.02.2022

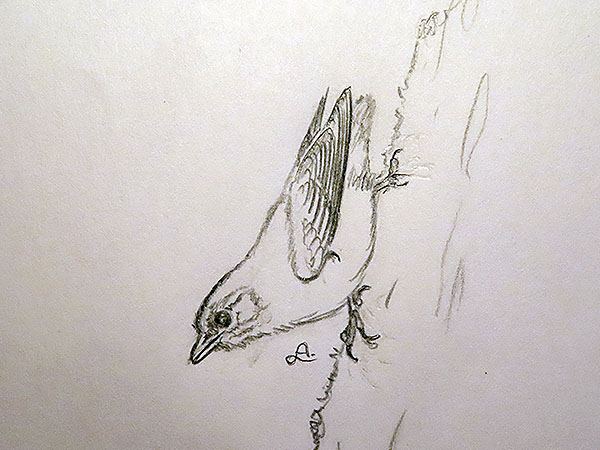

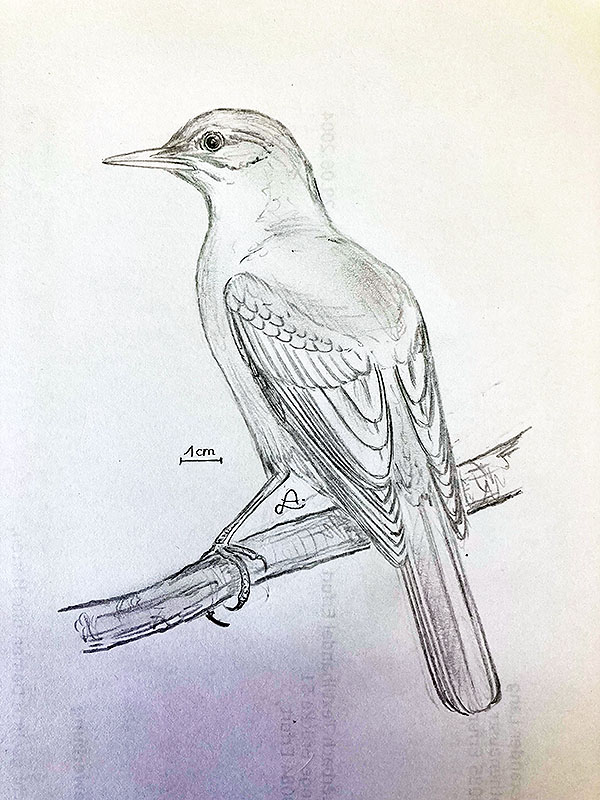

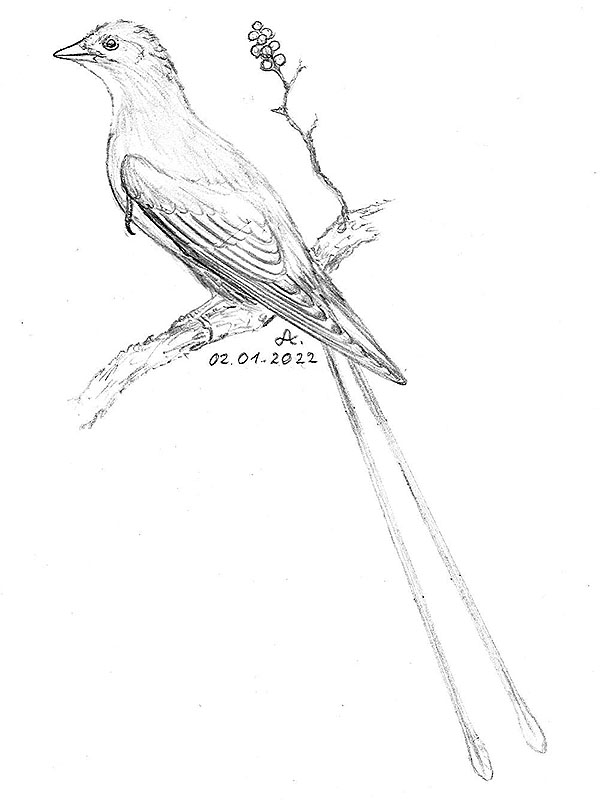

Horusitzky-Rotkehlchen (Erithacus horusitzkyi Kessler & Hír)

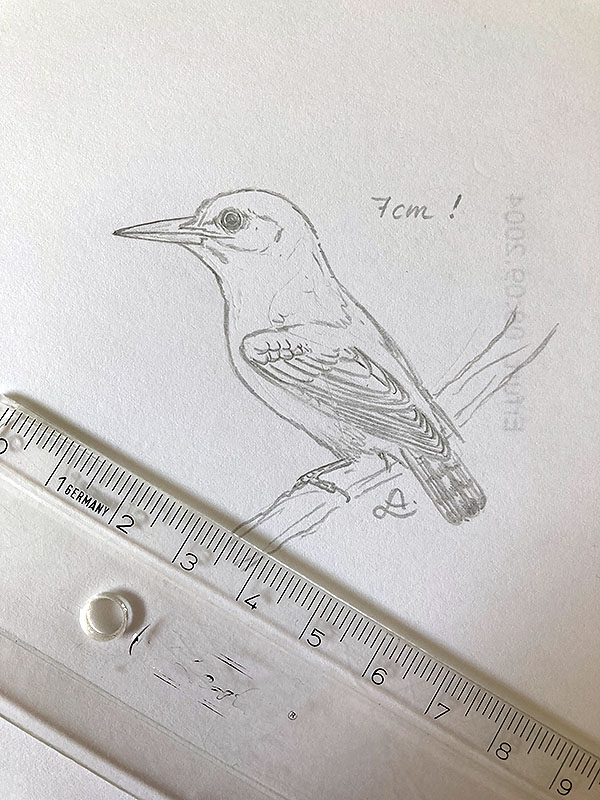

Momentan ist dies nur eine Skizze, ich denke ich werde noch etwas am Hintergrund arbeiten und eventuell die Haltung des Vogels noch etwas ändern.

*********************

bearbeitet: 01.02.2022

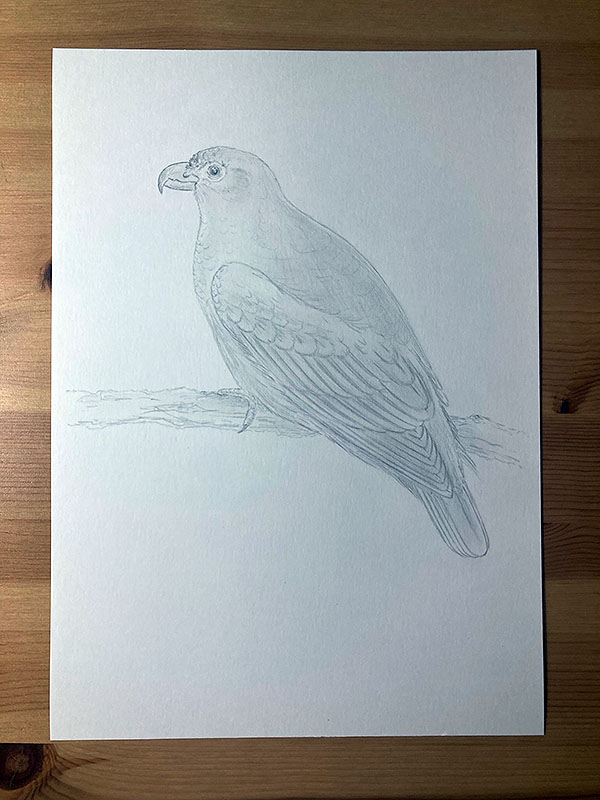

Eoconfuciusornis zhengi Zhang, Zhou & Benton

Diese Art wurde im Jahr 2008 beschrieben; sie stammt aus Schichten, die sich auf ein Alter von 131 Millionen Jahren datieren lassen, d.h. aus der Unterkreide. [1]

Das Typusexemplar weist im Bereich des Unterleibs kleine, runde Gebilde auf, die ursprünglich für Eier gehalten wurden, die aber mittlerweile als Samen eines Steineibengewächses (Podocarpaceae) identifiziert wurden, die der fossilen Form Carpolithus multiseminalis Sun et Zheng bzw. Strobilites taxusoides Sun & Zheng (siehe Darstellung) aus derselben Fundschicht ähneln, jedoch größer waren. [4]

Des Weiteren sind bei dieser Art Farbzellen erhalten, die es möglich machen, die Farben des Vogels zu Lebzeiten zu rekonstruieren: das Gefieder war hauptsächlich dunkelgrau mit irisierenden Federn im Kopf-Nacken-Bereich, die Kehle war offenbar rotbraun gefärbt, die Armschwingen mögen bräunlich gewesen sein, die Handschwingen sicher dunkler, eher schwärzlich. [3][5]

***

Der Vogel gehört zur Ordnung der Confuciusornithiformes, einer Gruppe von avialen Dinosauriern, die sehr gute Flieger gewesen sein dürften und bereits einen keratinösen Schnabel besaßen, die aber nur äußerst entfernt mit den heutigen Vögeln verwandt sind und auch nicht deren Vorfahren darstellen.

Zu Lebzeiten muss diese Art eine Länge von über 30 cm erreicht haben (inclusive der beiden verlängerten Schwanzfedern). [2]

*********************

*********************

Quellen:

[1] FuCheng Zhang; ZhongHe Zhou; Michael J. Benton: A primitive confuciusornithid bird from China and its implications for early avian flight. Science in China Series D: Earth Sciences 51: 625–639. 2008

[2] Matthew P. Martyniuk: A Field Guide to Mesozoic Birds and Other Winged Dinosaurs. Pan Aves 2012

[3] Yanhong Pan; Wenxia Zheng; Alison E. Moyer; Jingmai K. O’Connor; Min Wang; Xiaoting Zheng; Xiaoli Wang; Elena R. Schroeter; Zhonghe Zhou; Mary H. Schweitzer: Molecular evidence of keratin and melanosomes in feathers of the Early Cretaceous bird Eoconfuciusornis. Proceedings of the national Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113(49) 900-907. 2016

[4] Gerald Mayr; Thomas G. Kaye; Michael Pittman; Evan T. Saitta; Christian Pott: Reanalysis of putative ovarian follicles suggests that Early Cretaceous birds were feeding not breeding. Scientific Reports 10(19035): 1-10. 2020

[5] Pan Yanhong; Li Zhiheng; Wang Min; Zhao Tao; Xiaoli Wang; Xiaoting Zheng: Unambiguous evidence of brilliant iridescent feather color from hollow melanosomes in an Early Cretaceous bird. National Science Review. in press: nwab227. doi:10.1093/nsr/nwab227. 2021

*********************

bearbeitet: 02.01.2022

Kaririavis mater de Souza Carvalho et al.

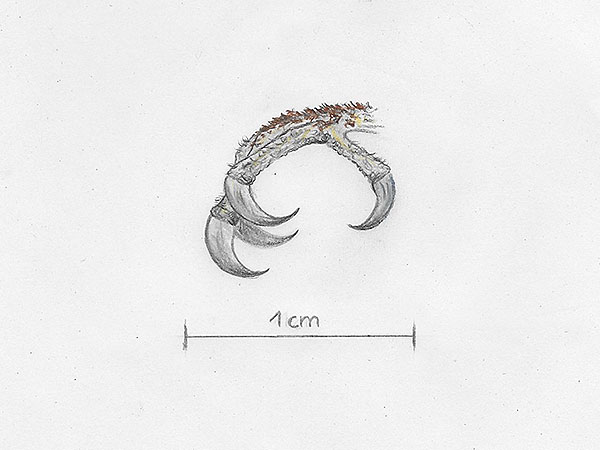

… just having been described from the Early Cretaceous Crato Formation in Brazil.:

This was a member of the Euornithes, which include all living birds, yet it does not belong to any of the living bird groups of course; it is the oldest member of that group known from South America (older ones were found in China).

The bird is known only from a single right foot that lacks some of its bones; the fossil also contains some feathers which indeed may belong to the bird. [1]

*********************

References:

[1] Ismar de Souza Carvalho; Federico L. Agnolin; Sebastián Rozadilla; Fernando E. Novas; José A. Ferreira Gomes Andrade; José Xavier-Neto: A new ornithuromorph bird from the Lower Cretaceous of South America. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology doi: 10.1080/02724634.2021.1988623. 2021

*********************

edited: 14.11.2021

What is/was Strix parvissima Ellman?

“Little Owl (Ruruwekau), Strix parvissima. A very scarce bird, not larger than a starling. The head is very large. I have never obtained a specimen, but have seen it among the forests. It is an exceedingly shy bird.” [1]

***

“In this division there is a most remarkable little owl, the smallest in the world. It is known to the natives as the ruru wekau; it has an unusually large head, flies by day, is exceedingly shy, and is about half the size of the common ruru. It inhabits dense forests.” [2]

***

“No. 6. – Strix parvissima, Ellman. (Zool., 1861)

Little Owl

Amongst the desiderata of our collections the Little Owl has for some time held a place; many doubt its existence, few have seen it, still fewer have preserved any note or observation concerning it. From the information that has been gleaned about this rare bird, it would appear that its habitat must be the bushes about the Rangitata River [Canterbury Region, South Island].

One correspondent saw it on the bank of a creek at no great distance from Mount Peel Forest, it was between the roots of a large tree; observation was drawn to it by the proceedings of several tuis, who were persecuting it to the best of their ability; it was whilst its attention was engaged by these noisy assailants that the bird was secured. It was about the size of a kingfisher, and its captor felt quite certain of its being an adult specimen; it was carried home to be shown as a curiosity, and was afterwards liberated. Unlike the more-pork, when captured it was exceedingly gentle.

Another specimen was procured by a gentleman in one of the bushes far above the Rangitata Gorge; on being observed on a branch of a tree, it was knocked down and caught during its fall; there was fur on its beak, as though it had not long before devoured a mouse; this bird was also set at liberty.

Two other instances of its occurrence have been communicated, but without further information. It may be mentioned that one of these was again on the Rangitata.

At Shepherd Bush Station, on the Rangitata, opposite Peel Forest, a specimen was observed in the house, greatly resembling A. Novae Zelandiae [ruru (Ninox novaeseelandiae)], except in size, which was about that of a kingfisher; it was most gentle in its habits, remaining quiet during the daytime and sallied forth in the evening, regaining its perch by entering through a broken window. This pretty little visitor thus frequented the house for about a fortnight; it should be added that the house stands close to a small bush composed chiefly of Leptospermum, Griselinia, etc., of which there are many aged specimens.

From these notices it may be safely inferred that the Little Owl is arboreal in its habits, and possibly not so strictly nocturnal as its better known congeners; whether it is to be considered identical with either of the species referred to by Dr. Finsch is, of course, at present unknown; it is certain it is not a tufted species, or such a remarkable form would have been noticed.” [3]

***

What can we make of this little owl that apparently once existed in New Zealand?

Are these accounts referring to an actual owl or rather to some other bird, maybe even to a last surviving population of the New Zealand Owlet-Nightjar (Aegotheles novaezealandiae (Scarlett))?

This nightjar species is known only from subfossil remains that date to 1200 AD and which usually are not found in association with Maori middens, it was also not necessarily a small bird and may have been quite the same size as the ruru and only slightly smaller than the larger whēkau (Ninox albifacies); furthermore it is thought to have been flightless or at least nearly so.

There is, however, a slight chance that these eyewitness accounts indeed refer to a last surviving population of this now extinct creature, we will probably never know for sure.

*********************

References:

[1] J. B. Ellman: Brief Notes on the Birds of New Zealand. The Zoologist 19: 7464-7473. 1861

[2] J. B. Ellman: Correspondence. The Press 3(136): 2. 1863

[3] T. H. Potts: On the birds of New Zealand (Part II.) Transactions and Proceedings of the New Zealand Institute 3: 59-109. 1870

*********************

Depiction: Paul Martinson

under creative commons license (4.0))

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

*********************

edited: 05.11.2021

Manumea

*********************

edited: 03.11.2021

The Manumea

There is probably no other bird on this planet that comes more closely to what could be called a cryptid than the Manumea, the Tooth-billed Pigeon (Didunculus strigirostris (Jardine)) of Samoa.

The species is known to inhabit, or at least to have inhabited, the rainforests of the islands of Nu’ulua, Savai’i and ‘Upolu, Western Samoa; in prehistorical times it was even more widespread. Nearly nothing is known about this species: the breeding behavior is still unknown, the same more or less applies to basically all of the bird’s habits.

As far as I know there are only about five or so photos of living individuals of the species, most of them, if not all, show the same bird that was kept in captivity for some time.

The latest sightings were of a juvenile bird in 2013, which also was photographed; than a bird was seen and heard calling in 2020, however, no photo had been taken this time. [1]

***

The Manumea is currently not kept in captivity and the wild population is estimated to be less than 100 – to about 300 birds, that’s not much and the species is in immediate danger of extinction.

Wouldn’t it be phantastic if even only a fraction of the amounts of money that are spend to prove the existence of such phantasy creatures like Bigfoot, Chupacabra or Mokele Mbembe would be used for something useful, for the search for the Manumea, for the rescue of this enigmatic yet indeed existing bird?!

*********************

References:

[1] Sapeer Mayron: Near-extinct manumea spotted in Savai’i. Samoa Observer 25/08/2020

*********************

(public domain)

*********************

edited: 03.11.2021

Are there Maori traditions about the extinct Moa(s)? part: 2

The Maori, the indigenous people of Aotearoa (New Zealand), have a very rich oral tradition that actually dates back to the time when their ancestors first arrived at the shores of the islands!

These traditions, however, have greatly been influenced by Europeans settlers, especially by missionaries, who tried to destroy the Maori by banning everything Maori: traditional clothing, traditional musical instruments, songs, religious beliefs, even the Maori language itself, everything was banned and violations were punished severely.

No one can say how much knowledge was destroyed during these times.

“…

Kotahi tonue tama

Te tiaki whenua,

Ko te kuranui,

Te manu a Rua-kapanga,

Itahuna e to tupuna, e Tamatea

Ki te ahi tawhito,

Ki te ahi tupua,

Ki te ahi na Mahuika.

Na Maui i whakaputa ki te ao

Ka mate i whare huki o Repo-roa,

Ka rere te momo, e tama e!“

This is the end part of a large Maori poem that can be dated back to the 14th century, around the time when the first Maori settlers arrived at the shores of Aotearoa (New Zealand).

The poem mentions the kuranui, the bird of Rua-kapanga, which is said to have been the first person to have spotted the bird; te kuranui might be translated as ‘the large red one’, ‘the large precious one’ or maybe as ‘the most precious one’.

Furthermore it also informs us about the fate of these kuranui(s): “… destroyed by your ancestor, Tamatea, with underground and supernatural fire, the fire of Mahuika (a fire goddess), brought to this world by Maui; they were driven into the swamps and perished …” [1]

*********************

References:

[1] Otto Krösche: Die Moa-Strausse, Neuseelands ausgestorbene Riesenvögel: Die neue Brehm-Bücherei 322. A. Ziemsen Verlag 1963

*********************

edited: 02.11.2021

Pā-Tangaroa – an extinct starling from the island of Mangaia?

Nowadays there is only one single species of starling in central Polynesia, the Rarotonga starling (Aplonis cinereacsens Hartlaub & Finsch), which occurs exclusively on the island of Rarotonga, the largest of the Cook Islands; another form, the Plain Starling (Aplonis mavornata Buller), itself a mystery for over a century, came from another of the Cook Islands, namely Ma’uke.

So, it’s pretty certain that other forms were once found on other islands in this archipelago, right?

I just found a clue in this direction when I was writing down the names from a list of birds compiled in the early 20th century by someone named F. W. Christian; this list is part of a kind of dictionary of the Mangaian dialect, the dialect spoken on the island of Mangaia, the southernmost and second largest of the Cook Islands.

Here a list of the bird names.:

“Pā-Tangaroa. – A speckled bird; somewhat larger than the Kere-a-rako. Frequents coconut palm blossoms.

Tangaa-‘eo. – The native Wood-pecker; blue above, yellow and white below.

Kere-a-rako. – A small yellow and green song-bird much resembling a canary.

Titi. – A bird living in the rocks and crags. Much relished for food. Cf. Maori Titi, the Mutton-bird. Sanskrit and Hindustani, Titti: Tittiri, the Partridge.

Mokora’a. – The Wild Duck, or rather, a small species of teal, found in abundance round Lake Tiriara.

Kauā. – A sea-bird.

Rakoa. – A sea-bird.

Torea. – A sea-bird.

Kotuku. – The Blue Heron.

Kakaia. – A beautiful small white tern or sea-gull.

Kotaa. – The Frigate or Boatswain Bird. Cf. Samoa, A ta fu,; id. Fijian, Kandavu; id. Uleai (W. Carolines) Kataf; id. Sonserol (S. W. Caralises) Gatyava; id. Cf. Sanskrit Gandharva, a celestial messenger: angel.

Tavake. – The Tropic Bird (Phaethon). Called in the Marquesas Tavae-ma-te-ve’o, from its two long red tail-feathers. Used in Polynesian head-ornaments. Cf. Ponape Chaok: Chik; id. Cf. Sanskrit Stabaka, Stavaka a peacock’s feather: tuft: plume.

Kara’ura’u. – A sea-bird.

Kururi: Kuriri. – The Sand-Piper.

Karavi’a. – The Long-tailed Cuckoo.

Kura-mō. – A small Parrakeet (on Atiu).” [1]

The respective scientific names of the birds.:

Pā-Tangaroa. – ?

Tangaa-‘eo. – Todiramphus ruficollaris

Kere-a-rako. – Acrocephalus k. kerearako

Titi. – Pterodroma nigripennis

Mokora’a. – Anas superciliosa

Kauā. – Numenius tahitiensis

Rakoa. – Puffinus lherminieri

Torea. – Pluvialis fulva

Kotuku. – Egretta sacra

Kakaia. – Gygis alba

Kotaa. – Fregata spp.

Tavake. – Phaethon rubricauda

Kara’ura’u. – Procelsterna cerulea

Kururi: Kuriri. – Tringa incana

Karavi’a. – Eudynamis taitensis

Kura-mō. – Vini kuhlii

***

All of these names can be assigned to actually existing bird species, with one exception – the first name.

So which species is hiding behind the name Pā-Tangaroa?

This is actually a rather unusual name for a Polynesian bird, and the reference to Tangaroa, one of the most important Polynesian gods, is very interesting. Perhaps a bird with such a name was also considered God-like or sacred, or at least as being tapu.

The description of this bird: speckled and slightly larger than the Kerearako (i.e. larger than 16 cm), often found on coconut flowers, fits a star of the genus Aplonis quite well, in fact it suits this genus more than any other genus in question.

So there was almost certainly once a star of the genus Aplonis that lived on the island of Mangaia, and its subfossil bones may sooner or later be discovered; the question is, did the species survive long enough that locals could at least remember that it was called Pā-Tangaroa? Given that research into the fauna and flora of the Cook Islands didn’t begin until the early 20th century … it is entirely possible!

***

I should also mention that this listing, which dates back to 1920, already mentions the Cook Island reed warbler (Acrocephalus kerearako Holyoak), which was not officially discovered until 1973 (and described a year later). [2]

*********************

References:

[1] F. W. Christian: List of Mangaia birds. The Journal of the Polynesian Society 29(114): 87. 1920

[2] D. T. Holyoak: Undescribed land birds from the Cook Islands, Pacific Ocean. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club 94(4): 145-150. 1974

*********************

*********************

edited: 01.11.2021

Are there Maori traditions about the extinct Moa(s)?

This is a very interesting question that was asked by many scientists – what does Maori lore tell us about the now extinct megafauna of New Zealand? The results of all previous investigations are rather sobering, all so-called traditional accounts seem to date to the time following the arrival of the Europeans in New Zealand.

I want to mention only one of them here.

The first account dates from the middle of the 19th century.:

“The natives speak of another member of this family, which they name the kiwi papa whenua, a still larger species, which they describe as having been full seven feet high; it likewise had a very long bill, with which it made large holes in the ground, in search after worms. This bird is now extinct, but there are persons living who have seen it. Rauparaha told me he had eaten it in his youth, which might be about seventy years ago [ca. 1785], and when that Chief died, his corpse was said to have been ornamented with some of its feathers.” [1]

***

This second account refers to the first one and was made just ten years later.:

“Kiwi Papa Whenua. Seven feet [ca. 2 m] high. One of the last birds to disappear. There are still men who have hunted it.” [2]

***

The Kiwi papa whenua accounts may indeed refer to one of the smaller or middle-sized moa species, one that was about 2 m tall and that may have survived longer than most of the other moa species, but probably not into the early- or middle 18th century; it might thus be referring to the so-called Upland Moa (Megalapteryx didinus (Owen)), a species that officially died out around 1500 AD.. However, when reading the first account, it is very clear that this description has been mixed with that of a typical kiwi, thus it is quite clear that these accounts are no eyewitness reports.

The term Kiwi papa whenua might be translated as ‘Ground kiwi’ or maybe ‘Kiwi of the land’ which is not very meaningful. It is furthermore rather unlikely that the Maori would have connected the diurnal, rather large, long-necked moa species with the completely distinct kiwi(s), thus it is very unlikely that the term ‘kiwi’ would have been used for any of these species.

Nevertheless, such old accounts remain very interesting, and I will go on posting more of them in the future.

*********************

References:

[1] Richard Taylor: Te Ika a Maui: or, New Zealand and its inhabitants, illustrating the origin, manners, customs, mythology, religion, rites, songs, proverbs, fables, and language of the natives: together with the geology, natural history, productions, and climate of the country; its state as regards Christianity; sketches of the principal chiefs, and their present position; with a map and numerous illustrations. London: Wertheim and Macintosh, 24, Paternoster-Row. 1855

[2] J. B. Ellman: Brief Notes on the Birds of New Zealand. The Zoologist 19: 7464-7473. 1861

*********************

edited: 01.11.2021

Kleiber

*********************

bearbeitet: 31.10.2021

Common Moorhen

… photographed in the city park of Gotha / Thuringia.

*********************

edited: 31.10.2021

Mt. Mutis Parrotfinch

This is a ‘new’ species that was discovered on Mt. Mutis in western Timor, Indonesia; it has not yet been described.

*********************

edited: 20.10.2021

Avian Musings – blog post from January 23, 2019

In his great blog (that I actually – and that’s no lie – look into at least once a week), Paul Cianfaglione writes about many bird-related things, including fine book reviews, very interesting insights into bird anatomy and everything else.

But his latest post is just unbeatable: he did make an extremely close inspection of a bird fossil from Messel that he owns.:

“Messel Bird Fossil offers unique feather preservation, and more” from January 23, 2019

***

I personally have never seen close-ups of a bird fossil that are so razor-sharp and detailed!

And his bird shows features not known in any living bird – at least not all of them together in one bird.:

The beak is very big and hooked like the beak of a bird of prey or a owl, and it appears to have had sensory pits, the body feathers appear somewhat hair-like, the wing coverts are fluffy, also probably somewhat like the feather edges of recent owls, and the primaries have extremely strange appendages not known in that way from any other bird, living or extinct, but somewhat reminding on the wings of a waxwing.

What kind of a bird was that?

Well, I could try to do a reconstruction, should I?

Gosh, this is so exciting! 🙂

***

The Avian Musings blog does not longer exist, unfortunately.

*********************

edited: 03.09.2021

LKM-Pal 7.451 a+b

This is one of two passerine bird species recently found in middle Miocene deposits in Austria, this one is known from a partial skull and several other quite shredded bones while the second one is known only from a sternum.

*********************

References:

[1] Johannes Happ; Armin Elsler; Jürgen Kriwet; Cathrin Pfaff; Zbigniew M. Bochenski: Two passeriform birds (Aves: Passeriformes) from the Middle Miocene of Austria. PalZ (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12542-021-00579-2

Komako – The Mangareva Reed Warbler

The Mangareva Reed Warbler (Acrocephalus astrolabii Holyoak & Thibault), only described in 1978, is one of the many mysterious birds whose cases were solved only quite recently.

The species was restricted to the Gambier Islands, where it was at least found on the biggest of the islands, Mangareva.

The species disappeared sometimes during the early or middle 19th century, but the natives still recalled the former presence of it and were also still using its name.:

“She [the daughter of the Chief of the island of Taravai] has not seen the “Komaku” herself, but her father, the Chief, has. He gave us the name and says he saw them about thirty or forty years ago.” [1]

***

The species apparently died out sometimes around the middle 19th century; it is, however, possible that it survived into the middle of the 20th century …:

“Signalons aussi qu’une fauvette fut observée sur l’îlot Tepapuri en 1971 (Thibault, 1973b). Ce dernier oiseau, blanchâtre dessus et brun dessous, devait être un erratique de la forme habitant, les atolls au nord des Gambier, A. caffer ravus.“ [2]

translation:

“Note also that a warbler was observed on Tepapuri islet in 1971 (Thibault, 1973b). This last bird, whitish above and brown below [I’m quite sure that it should be exactly reversed], must have been an erratic of the form inhabiting the atolls north of the Gambier, A. caffer ravus.”

I somewhat doubt that assumption, and this account may indeed be the very last sighting of a Mangareva Reed Warbler that took place on one of the northernmost motu of the Gambier Island’s fringing reef.

*********************

References:

[1] Whitney South Sea Expedition of the American Museum of Natural History: Voyage of the ‘France’ from Timoe Atoll to the Mangareva Islands; Voyage to Marutea. April 25 – May 14, 1922. Extracts from the Journal of Ernest H. Quayle; Assistant Field Naturalist. Book XXV through Book XXVIII. April 1 – June 24, 1922

[2] D. T. Holyoak; J.-C. Thibault: Contribution à l’étude des oiseaux de Polynésie orientale. Mémoires du Muséum national d’histoire naturelle 127(1): 1-209. 1984

[3] Alice Cibois; Jean-Claude Thibault; Eric Pasquet: Molecular and morphological analysis of Pacific reed warbler specimens of dubious origin, including Acrocephalus luscinius astrolabii. Bulletin on the British Ornitologists’ Club 131(1): 32-40. 2011

*********************

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

*********************

edited: 08.08.2021

Mangareva Kingfisher

The Mangareva Kingfisher still is one of the most enigmatic birds I am aware of so far.

The species inhabited the Gambier Islands, and another species occurring 1000s of km to the northwest of it, the Niau Kingfisher (Todiramphus gertrudae Murphy), is still officially assigned to this bird as a subspecies.

I have desperately tried to find the original description of this species, and here it is.:

“Il existe, en effet, depuis longtemps dans les galeries du Muséum un Martin- pêcheur qui a été rapporté en 1841 de Mangarewa (archipel Gambier) par l’Astrolabe (Voyage au Pôle Sud) et qui répond exactement à la description et à la figure de l’Halcyon Reichenbachi. Cet oiseau a le sommet de la tête d’un roux qui va en s’éclaircissant et tire au blanc jaunâtre du côté, du front, mais qui est assez intense sur le vertex où se détachent quelques plumes vertes. Sur les oreilles il existe aussi, de chaque côté une tache verte, passant au noirâtre en arrière et tendant à rejoindre une bande noire qui fait le tour de l’occiput. Cette bande foncée limite en dessus un large collier blanc, un peu sali par quelques taches noires, qui se fond sur les côtés dans la teinte blanche qui couvre toutes les parties inférieures du corps, les flancs seuls offrant un peu de roux et encore sur des points cachés entièrement par les ailes. Celles-ci sont d’un vert légèrement bleuâtre, avec des lisérés roux très fins au bord des couvertures alaires. La queue est également d’un vert bleuâtre au milieu, d’un vert mélangé de grisâtre sous lespennes externes, qui sont d’ailleurs incomplètes. Enfin le bec est noir et la mandibule, inférieure blanche ou plutôt jaunâtre dans toute sa portion basilaire. Les pattes sont d’un m brun foncé. La longueur totale de l’oiseau est de 0,170; l’aile mesure 0,090, la queue 0,880, le bec 0,018; le tarse 0,014. Dès 1889, en faisant une revision des Alcédinidés du Muséum en vue de leur instal- lation dans les nouvelles galeries, j’avais désigné ce Martin-pêcheur de Mangarewa sous le nom d” Halcyon Gambieri; mais je n’en avais pas publié la description jusqu’à ce jour.” [1]

translation:

“For a long time, there has been a kingfisher in the galleries of the Museum who was brought back in 1841 from Mangarewa (Gambier Archipelago) by the Astrolabe (Journey to the South Pole) and who exactly corresponds to the description and the figure of Halcyon Reichenbachi. This bird has the top of the head red that brightens to yellowish white on the side of the forehead but is quite intense on the vertex where some green feathers stand out. On the ears there is also, on each side a green patch, passing blackish back and tending to join a black band that goes around the occiput. This dark band has a large white necklace on top, a little dirty with a few black spots, which is melting on the sides into the white hue that covers all the lower parts of the body, only the flanks offering a little russet and are, on some points, hidden entirely by the wings. These are a slightly bluish green, with very fine red rims at the edge of the wing coverts. The tail is also bluish green in the middle, of a green mixed with greyish under the outer feathers, which are also incomplete. Lastly, the beak is black, and the mandible underneath is white or rather yellowish throughout its base portion. The legs are of a dark brown. The total length of the bird is 0,170; the wing measures 0,090, the tail 0,880, the beak 0,018; Tarsus 0,014. As early as 1889, by making a revision of the Alcedinidae of the Museum with a view to their installation in the new galleries, I had designated this kingfisher of Mangarewa under the name of Halcyon Gambieri; but I had not published the description so far.“

***

What I am wondering about most is the fact that the Mangareva – and the Niau Kingfishers still are regarded to as a single species; on the other hand, both forms are rather similar to each other.

Which of the many other Polynesian islands might once have harbored their own kingfisher forms not known to us today?

*********************

*********************

[1] M. E. Oustalet: Les Mammifères et les oiseaux des iles Mariannes. Nouvelles archives du Muséum d’histoire naturelle 3(7): 141-228. 1895

[2] D. T. Holyoak; J. C. Thibault: Halcyon gambieri gambieri Oustalet, an extinct Kingfisher from Mangareva, South Pacific Ocean. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club 97(1): 21-23. 1977

*********************

edited: 08.08.2021

Anthus ruficollis (Rothschild & Hartert)

*********************

edited: 18.07.2021

Mäusebussard

Schwarzspecht

Seltsame Kreidezeit-Füße – Teil 4: YLSNHM01001

YLSNHM01001 ist ein winziges Bernsteinfossil (ca. 2,5 x 1,8 cm), das Teile eines Vogelfußes bzw. Reste der Haut die diesen Fuß einst umgab, inklusive einer der Fußkrallen sowie Teile der Schwanzfedern umfasst.

Trotz der schlechten Erhaltung steht fest, dass es sich hierbei um einen enantiornithiden Vogel handelt sowie ebenfalls um eine bislang unbekannte Art.

Der Fuß (inklusive der Krallen) hat eine Länge von ca. 1,5 cm. Der vierte Zeh des Fußes ist in seinem Umfang etwa doppelt so groß wie die übrigen Zehen, so weit diese zu erkennen sind. Er erscheint auffällig geschwollen, und eventuell litt dieser Vogel an einer Infektion dieses Zehs. Es ist aber auch möglich, dass es sich hierbei um Verwesungsspuren handelt, worauf auch zahlreiche warzenartig aussehende Blasen hindeuten, die sich entlang der erhaltenen Hautpartien erkennen lassen.

Der Gesamtbau des Fußes lässt darauf schließen, dass YLSNHM01001 ein kleiner insektenfangender Miniaturraubvogel gewesen sein dürfte. [1]

*********************

Referenzen:

[1] Lida Xing; Ryan C. McKellar; Jingmai K. O’Connor; Kecheng Niu: A mid-Cretaceous enantiornithine foot and tail feather preserved in amber. Scientific Reports 9 (1): 1–8. 2019

[2] A. D. Clark; J. K. O’Connor: Exploring the ecomorphology of two Cretaceous enantiornithines with unique pedal morphology. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 9: 654156. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.654156. 2021

an den Füßen und den Schwanzfedern muss ich noch mal arbeiten …

*********************

bearbeitet: 19.06.2021

Sie sind wieder da! :-)

*********************

bearbeitet: 02.05.2021

Singdrossel

*********************

bearbeitet: 28.04.2021

Rotkehlchen

*********************

bearbeitet: 28.04.2021

Fitis

*********************

bearbeitet: 28.04.2021

Gimpel

*********************

bearbeitet: 28.04.2021

Kleiber

**********************

bearbeitet: 27.04.2021

Feldsperling

Feldsperlinge gehören zu meinen absoluten Lieblingsvögeln, wenn man genau hinschaut kann man in ihrem kastanienbraunen Käppchen einen ganz zarten Hauch von Violett erkennen.

*********************

bearbeitet: 25.04.2021

Mäusebussard

Neben dem Mäusebussard sieht man hier oft Rotmilane (Milvus milvus) und immer häufiger Weihen, vermutlich Rohrweihen (Circus aeruginosus), die man an ihrem einzigartigen Flugstil erkennen kann (wenn man ihn einmal gesehen und sich eingeprägt hat). 🙂

*********************

bearbeitet: 25.04.2021

Höckerschwan

*********************

bearbeitet: 25.04.2021

Graugans

*********************

bearbeitet: 25.04.2021

Jacamatia luberonensis Duhamel et al.

*********************

bearbeitet: 17.04.2021

Crosnoornis nargizia Bochenski, Tomek, Bujoczek & Salwa

*********************

bearbeitet: 16.04.2021

Shengjingornis yangi Li, Wang, Zhang & Hou

Dieses nette kleine Vögelchen, welches in etwa eine Länge von nicht ganz 20 cm erreicht haben dürfte, stammt aus Schichten, die sich auf ein Alter von 122 Millionen Jahren datieren lassen.

Die Art ist bislang wohl nur anhand eines einzigen Skelettes bekannt, das dafür aber vollständig ist; das Gefieder ist allerdings nicht erhalten.

Der Schnabel, wenn man das Schnäuzchen denn so nennen möchte, war leicht abwärts gebogen und trug ganz vorn noch ein paar winzige Zähnchen. [1]

*********************

*********************

Quelle:

[1] Li Li; Jinqi Wang; Xi Zhang; Shilin Hou: A new enantiornithine bird from the lower Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation in Jinzhou Area, western Liaoning Province, China. Acta Geologica Sinica 86(5): 1039-1044. 2012

*********************

bearbeitet: 13.04.2021

IVPP V13939

Hinter dieser Buchstaben- und Nummernfolge verbirgt sich ein interessantes Vogelfossil aus der Unteren Kreide Chinas.

Das Fossil besteht aus dem hinteren Teil des Vogels, der Kopf und Teile des Vorderskelettes fehlen, Federn sind ebenfalls erhalten, und hier fallen vor allem einige relativ lange Federn an den Unterschenkeln auf, die etwa die halbe Länge des Beinknochens aufweisen.

Die Art wurde bislang offenbar nicht beschrieben oder benannt, ist aber in Matthew P. Martyniuks “A Field Guide to Mesozoic Birds and other Winged Dinosaurs” abgebildet, wobei ich die hier dargestellten Beinfedern am entsprechenden Fossil vermisse. Die Federn am Fossil ähneln eben nicht den Körper- oder Flugfedern wie im Buch dargestellt, sondern weisen einen sehr viel einfacheren Aufbau auf. Alles in allem erinnern diese Beinfedern sehr an die heutiger Vögel wie z.B. einigen Greifvogelarten, sie dürften daher keinen besonderen Einfluss auf die Flugeigenschaften des Vogels gehabt haben.

*********************

*********************

Quellen:

[1] Fucheng Zhang; Zhonghe Zhou: Leg feathers in an Early Cretaceous bird. Nature 431: 925. 2004

[2] Matthew P. Martyniuk: A Field Guide to Mesozoic Birds and other Winged Dinosaurs. Pan Aves 2012

*********************

bearbeitet: 12.04.2021

Graculavus augustus Hope

Dieser immer noch recht rätselhafte Vogel, auch bekannt als “Ornithurine C”, wird in einer Studie aus dem Jahr 2011 erwähnt, die sich mit dem Aussterben mehrerer Vogel-Kladen am Ende der Kreidezeit befasst. [1]

Die Art scheint anhand von mindestens vier Coracoiden bzw. Überresten davon bekannt zu sein, die als “SDSM 64281A”, “SDSM 64281B”, “UCMP 175251” und “MOR 2918” bezeichnet werden und die überwiegend aus Schichten der späten Kreidezeit stammen, aber eben auch aus Schichten, die dem untersten Paläozän zugeordnet werden können.:

“One of these species, Ornithurine C, is known from the Paleocene and therefore represents the only Maastrichtian bird known to cross the K–Pg boundary.” [1]

Übersetzung:

“Eine dieser Arten, Ornithurine C, ist aus dem Paläozän bekannt und stellt daher den einzigen Maastricht-Vogel dar, von dem bekannt ist, dass er die K/T-Grenze überschreitet.”

***

Laut den Autoren könnte diese Art mit einer Art identisch sein, die als Graculavus augustus Hope bezeichnet wurde, ein Vogel, der anscheinend zu den Charadriiformes gehört, sich aber sehr von allen heute lebenden charadriiformen Vögeln unterschied, zu Lebzeiten muss er an eine Art Riesen-Brachvogel oder -Triel erinnert haben. [2]

Die Art ist tatsächlich die einzige bisher bekannte Vogelart, der es gelungen ist das Massensterben am Ende der Kreidezeit zu überleben!

*********************

*********************

Quellen:

[1] Nicholas R. Longrich; Tim Tokaryk; Daniel J. Field: Mass extinction of birds at the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) boundary. PNAS 108 (37) 15253-15257. 2011

[2] Nicholas R. Longrich; Tim Tokaryk; Daniel J. Field: Mass extinction of birds at the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) boundary. PNAS 108 (37) 15253-15257. 2011. Supplementary Information

*********************

bearbeitet: 12.04.2021

Zilpzalp

*********************

bearbeitet: 11.04.2021

Stieglitz

*********************

bearbeitet: 11.04.2021

Turmfalke

*********************

bearbeitet: 11.04.2021

Foshanornis songi Zhao, Mayr, Wang & Wang

Phirriculus pinicola Mlíkovský & Göhlich

Würde man eine Zeitreise ins miozäne Europa unternehmen, etwa vor 23 bis 16 Millionen Jahren, würde man sich alsbald wundern ob man wirklich noch in Europa ist oder doch in Afrika; zahlreiche der heute nur noch in Afrika vorkommenden Vogelfamilien waren damals auch weit nördlich der Sahara zu finden, die Baumhopfe sind eine dieser Vogelfamilien.

Der Kiefernrenner (so die Übersetzung seines wissenschaftlichen Namens) erreichte eine Länge von etwa 20 cm, ansonsten ähnelte die Art wohl weitgehend den heutigen Baumhopfen. [1]

*********************

*********************

Quelle:

[1] Jiří Mlíkovský; Ursula B. Göhlich: A new wood-hoopoe (Aves: Phoeniculidae) from the early Miocene of Germany and France. Acta Soc. Zool. Bohem 64: 419-424. 2000

*********************

bearbeitet: 03.04.2021

Protornis glarniensis von Meyer

Motmots, wegen ihrer gezähnten Schnabelkanten auch Sägeracken genannt, sind heute mit einigen Arten in Süd- und vor allem Zentralamerika verbreitet, alle Arten sind ausgesprochen farbenfroh.

Diese bislang älteste bekannte Art war offenbar kleiner als die kleinste der heute lebenden Motomot-Arten (sie erreicht in meiner Rekonstruktion eine Größe von nur etwa 13 cm, abhängig von der Länge der Schwanzfedern).

*********************

*********************

bearbeitet: 02.04.2021

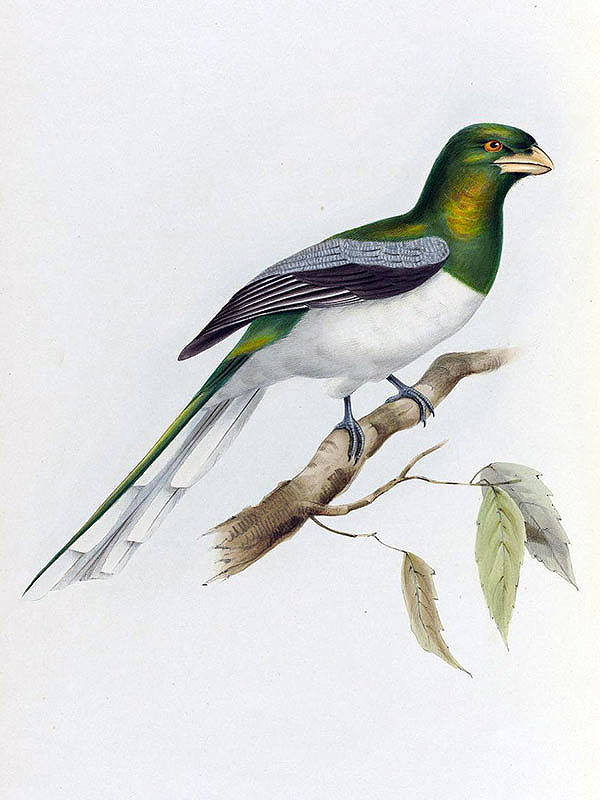

Riesentrogon

Riesentrogon (Trogon gigas Vieill.)

Ursprünglich ist diese Form wohl anhand von drei oder vier Exemplaren bekannt, über deren Verbleib offenbar nichts bekannt ist.

“Ganze Oberseite, Kehle und Halsseiten glänzend goldgrün, Brust und Bauch weiss; Schwanz oben goldgrün unten graulich-weiss, Flügelmitte fein schwärzlich grün und weiss quergestreift, Schwingen braunschwarz, Schnabel gelb, Füsse braun.” [2]

Der Vogel soll eine Größe von 18 Inches erreicht haben, das entspricht etwas über 45 cm, wirklich sehr groß für einen Trogon; er soll aus Asien stammen, wobei die genaue Herkunft nicht bekannt ist (entweder Java oder Molukken).

***

Der folgende Text stammt von keinem Geringeren als François Le Vaillant (1753-1824).:

“I have only seen three specimens of this fine species; one in the collection of M. Carbintus at the Hague, a second at Rotterdam in the possession of M. Gevers, and another in the large and splendid collection of my friend M. Temminck at Amsterdam. This individual, from which our figure was taken, was sent along with many other birds from Java. I have seen a fourth specimen in the Paris Museum; but as it was in an imperfect state, it has not as yet been placed in the gallery.” [1]

Übersetzung:

“Ich habe nur drei Exemplare dieser schönen Art gesehen; eine in der Sammlung von M. Carbintus in Den Haag, eine zweite in Rotterdam im Besitz von M. Gevers und eine weitere in der großen und prächtigen Sammlung meines Freundes M. Temminck in Amsterdam. Dieses Individuum, anhand dessen unsere Abbildung angefertigt wurde, wurde zusammen mit vielen anderen Vögeln aus Java geschickt. Ich habe ein viertes Exemplar im Pariser Museum gesehen; aber da es unvollkommen war, wurde es noch nicht in die Galerie aufgenommen.“

***

Es könnte sich natürlich um eine tatsächlich existierende Art handeln, die mittlerweile ausgestorben ist; es ist aber durchaus wahrscheinlicher, dass es sich auch hierbei um eine der künstlich zusammengebauten ‘Arten’ handelt, die in den ornithologischen Abhandlungen des F. Le Vaillant aus dem ausgehenden 18. Jahrhundert offenbar gehäuft auftauchen ….

*********************

(public domain)

*********************

Quellen:

[1] John Gould: A monograph of the Trogonidae, or family of trogons. London: the author 1835-1838

[2] Jean Louis Cabanis; Ferdinand Heine: Museum Heineanum: Verzeichniss der ornithologischen Sammlung des Oberamtmann Ferdinand Heine, auf Gut St. Burchard vor Halberstadt. Halbertstadt: in Commission bei R. Frantz 1850-1863

*********************

bearbeitet: 01.04.2021

Bachstelze

Diese Fotos zu ‘schießen’ war gar nicht so einfach, das Vögelchen war sehr geschäftig und für jedes gelungene Bild gibt es mindestens drei misslungene. 🙂

*********************

bearbeitet: 31.03.2021

Buchfink

Die Buchfinken singen gerade überall im Wald, allerdings singen nur die Männchen.

*********************

bearbeitet: 31.03.2021

Blaumeise

Meisen sind ziemlich schwer zu fotografieren, sie lassen einen nicht wirklich nah an sicher heran und halten auch kaum länger als eine Sekunde still.

*********************

bearbeitet: 31.03.2021

Rotkehlchen

*********************

bearbeitet: 31.03.2021