P. H. Bahr in the year 1912 quotes a Dr. B. Glanvill Corney, at that time Chief Medical Officer in the Fiji Islands.:

“There is, or was until eight or ten years ago, a bird in the interior and northern coast of Vitilevu called the ‘Sasa’; described as having speckled plumage and running along the ground among reeds, cane-brakes, and undergrowth. … The Sasa did not fly, and seems to have been a mound-builder. I once met with some dogs in a remote mountain village that the natives had specially trained to hunt the Sasa, which they described as Koli dankata sasa, i. e. Sasa-catching dogs; but I never succeeded in seeing a Sasa, nor did my friend Mr. Frank R. S. Baxendale, who, as Assistant Resident Commissioner in the hill districts, lived for more than a year in the Sasa country. His successor, Mr. Georgius Wright, however, had several living specimens in his possession for some time, and told me that he considered they were Megapodes of the same or of an allied species to those met with in the island of Ninafou [Niuafo’ou] (Boscawen Island) and in Samoa. Some natives linkened them to Guinea-fowl, but said they were not so large as the latter, and that they laid a single egg. Between the years 1876 and 1905 they were still comparatively common and well known in the locality mentioned (where there are only a very few Europeans).” [1]

***

What follows is an account by Rollo H. Beck, an American ornithologist, who quotes some notes that he received by a Mr. G. T. Barker on June 5, 1925, during a stay on the island of Viti Levu, Fiji.:

“Saca Megapode

On the Tova Estate (Viti Levu Bay) one day, as I was riding toward the Wainibaka River, I heard a zooming noise on the rocks at my right. I dismounted to ascertain, if possible, what it was, as the place which had no trees, ws such an unusual one for a pigeon. The note, too, was different, having a more vibrant tone.

Grawling twenty feet along a runway but keeping myself hidden I came upon an abandoned clearing covered with short grass. The bird was about tne yards away. It ws slightly smaller than an English game rooster, had an aggressive head with yellow beak, and a stumpy tail. The coloring which was the same on the head as on the body was a mixed yellow, approaching red, and dingy black.

The bird continued its calling for a few minutes, and was answered from the far end of the clearing. Suddenly it took alarm, and as it flew out of the clearing I saw that under the rudimentary wings there were no yellow feathers. The wings had no long feathers made a whirring sound when the birds flew. I also noticed that its legs were stout, of yellow color, and that the foot had three toes. On questioning the natives, I was told that about sixty years ago there was a great area of grass country in that part, owing probably to a denser population, and also to the fact that the people were more industrious. At that time they used to hunt the bird with dogs and would secure up to fifty in a day. Even up to the coming of the mongoose, hese birds were still hunted, but owing to the spreading of the reeds over the country the catch became small.

The birds nested, generally, under the shelter of the dead leaves of the tree fern, never out in the open, and the birds used to take turns sitting on the nest. The natives described the eggs as being white, quite round, generally one, but on rare occasions, two in a nest. They used to hunt for the eggs, and when all hands were out, as many as a hundred a day would be secured. The eggs were hatched under hens in the village, but the saca always went back to the grass and would not remain in the town.

About two years after I had seen the bird, a dependable native who had hunted the birds in his youth, told me that he had seen a pair about two miles away from The place where I had observed them. Twenty was the largest number that had been observed in one flock.

The natives said that the flesh of the saca was dark, and always lean. Its wings seem to have been of some use for the bird is called in that part “the bird that lands on eight hillocks before being cought.”

The annual rainfall in that region averages ninety inches.” [2]

In my humble opinion this whole description, except for the nesting behaviour, sounds a lot like the description of a species of megapode (Megapodius sp.).

“Yasaca

This bird I have never seen, but from all accounts it differs from the saca. First it was called “Nasataudrau”, literally, “in hundreds”, meaning that a flock would be of about one hundred. It was said of them hat they buried their eggs for the sun to hatch out.

Personally, I am doubtful if this bird ever existed in Fiji. I remember of asking a Sabeto Chief in the year 1890 if he had ever seen one – Sabeto, to the Segatoka River, being the region where the ordinary “saca” was most plentiful. This chief was then a man over sixty years old; now add on the thirty-five years since that time – ninety five years ago, and he had never seen yasaca. He had only heard the trdition in his youth.

I am inclined to believe that the natives of this region brought the tale whith them from the Solomon Islands, where megapodes still are found. See, “A Naturalist Amongst the Head Hunters” by Woodward. Mr. A. Barker has a copy of this book. There is a remarkable similarity of language between that part of the Solomons and Fiji, hence the tradition.” [2][4]

***

It is now well known that the Fiji Islands indeed were inhabited by at least two species of megapode, the Consumed Scrubfowl (Megapodius alimentum Steadman) and the Viti Levu Megapodius (Megapodius amissus Worthy). [3]

It is not really known when exactly these species disappeared; the abovementioned accounts, however, show that at least one of the species survived well into quite modern times.

*********************

References:

[1] P. H. Bahr: On a Journey to the Fiji Islands, with Notes on the present Status of their Avifauna, made during a Year’s Stay in the Group, 1910-1911. The Ibis 9(6): 282-313. 1912

[2] Whitney South Sea Expedition of the American Museum of Natural History. Extracts from the journal of Rollo H. Beck. Vol. 2, Dec. 1923 – Aug. 1925

[3] T. H. Worthy: The fossil megapodes (Aves: Megapodiidae) of Fiji with descriptions of a new genus and two new species. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 30(4): 337-364. 2000

[4] Danke Hr. Antonius, für den Hinweis, damit liegen Sie natürlich vollkommen richtig! 🙂

*********************

edited: 31.01.2022

Tag Archives: Fiji

A Fijian quail?

Was there formerly a quail species living on the Fijian Islands?

Well, here is an account by Rollo H. Beck, an American ornithologist, who quotes some notes that he received by a Mr. G. T. Barker on June 5, 1925, during a stay on the island of Viti Levu, Fiji.:

“Moa (Quail)

It is commonly said, by whites, that quail are the offspring of imported birds, but this cannot be so for I have tales that run back for hundreds of years mentioning this bird. A Mr. Coster who was one of the first white settlers on the Island of Koro said that quail were present in great numbers when he arrived there and this was many years back.” [1]

Indeed, there was a quail species living on the Fijian Islands, and it still does, because this account clearly refers to the Brown Quail (Synoicus ypsilophorus ssp. australis (Latham)) (see photo), an Australian species that was introduced to the Fijian Islands sometimes in the early 1900s.

The species is commonly called moa on the islands, it was introduced at least to the islands of Makogai, Vanua Levu, and Viti Levu; it is, however, now apparently restricted to the (artificial) grasslands of Vanua- and Viti Levu. [2]

*********************

(under creative commons license (3.0))

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0

*********************

References:

[1] Whitney South Sea Expedition of the American Museum of Natural History. Extracts from the journal of Rollo H. Beck. Vol. 2, Dec. 1923 – Aug. 1925

[2] Edward Narayan: Troublesome birds of Fiji Islands. Lulu, Inc. 2014

*********************

edited: 29.07.2020

A Fijian hummingbird?

Rollo H. Beck, an American ornithologist, quotes some notes that he recieved by a Mr. G. T. Barker on June 5, 1925, during a stay on the island of Viti Levu, Fiji: ‘Notes by Mr. G. T. Barker, Suva, Fiji. June 5, 1925’.

One of these notes is about an alleged Fijian hummingbird.:

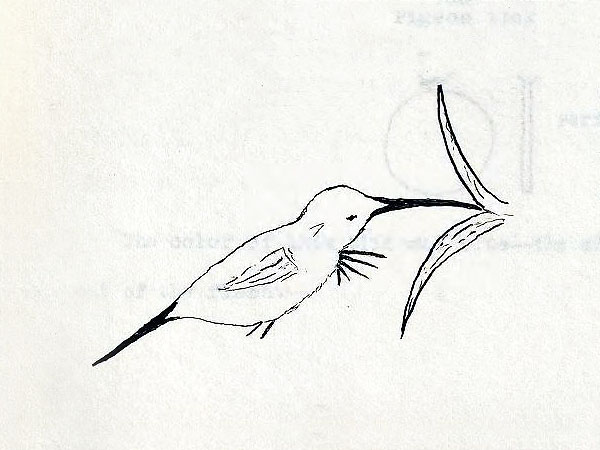

“Humming bird

One evening as I was sitting on the steps, I saw what I took to be a night moth settle on a hibiscus flower. …

The supposed moth kept its wings in rapid motion, while poised before the flower sucking the honey with its long slender bill.

I struck the “moth” with a fly switch which I had in my hand, and on picking it up, found that I had killed a small bird. I had seen only the pictures of humming birds but I concluded that this was one. Its slightly curved bill was black, as was the slender, pointed tail; the fine feathers on the breast were a bright red; the shoulders and patch under the tail were of darker tone.

Herewith is a sketch drawn to scale, which I made the next morning, after I found that the rats had eaten the bird from the wall where I pinned it.

1921“

(public domain)

“Feathers, fine as the fur of flying fox

Wings, very small

Body, red

Head and back, darker than breast

Bill and legs, black” [1]

Of course, hummingbirds are not found outside of the Americas, and this anecdote is

supposed to have taken place on the island of Viti Levu, Fiji.

But what kind of bird is involved in this story then?

I have to confess that I have no real idea, the most likely candidate is the orange-breasted Myzomela (Myzomela jugularis Peale), however, this species hasn’t a red body.

***

I personally think that this account is a very bad eyewithness records, made by someone not really interested in the natural world.

*********************

References:

[1] Whitney South Sea Expedition of the American Museum of Natural History. Extracts from the journal of Rollo H. Beck. Vol. 2, Dec. 1923 – Aug. 1925

*********************

edited: 14.03.2020

Was there once a Giant Kingfisher living on the Fiji Islands?

The Collared Kingfisher (Todiramphus chloris (Boddaert)) has a extremely wide distribution and occurs from parts of Arabia well into western Polynesia; it is the only kingfisher living on the Fiji Islands (with three endemic subspecies) – yet, may there once have been another kingfisher species?

Photo: Tom Tarrant

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0

Rollo H. Beck, an American ornithologist, quotes some notes that he received by a Mr. G. T. Barker on June 5, 1925, during a stay on the island of Viti Levu, Fiji: ‘Notes by Mr. G. T. Barker, Suva, Fiji. June 5, 1925’.:

“Giant Kingfisher

I saw this bird, or a single bird at least, on two occasions and it rose, both times, from nearly the same place. On the last occasion, I was on the lookout for it and it passed within twenty feet in front of me so that I had a good opportunity to see it clearly. I was riding down from the village of Navuniwi, Viti Levu Bay, toward the beach and it was from a patch of swampy ground on my left that the bird arose.

The kingfisher was fully eleven inches long, with the same colored plumage as the small kind only more dingy. The blue was not so bright, and the white feathers on the wings were discolored. The back was nearly black. Its flight was heavy-much slower than that of the small species, and as it flew in a straight line toward the mangrove swamp on my right, I noticed that it held its head in a line with the shoulders.

Natives told me that these giant kingfishers were plentiful in the early days, but as the bird nested in the low mangrove, it has practically disappeared since the advent of the mongoose which is a vertitable beach comber, haunting the swamps and beaches. About twenty-five years previously I had seen one of them back of Ovalau, but was told that it was only stray in that part.

On the second occasion of my seeing the giant flycatcher [indeed, he writes flycatcher here instead of kingfisher], I dismounted from my horse and went into the swampy patch, finding that the bird had been eating the native sila (Job’s tears) [Coix lacryma-jobi (L.) Lam.].

Ordinary Flycatcher [?]

It is generally supposed that this bird is an insect eater, and does not eat fish, but this is not invariably so. As I was coming out of the Wainidoi River, ten miles below Suva, I saw a belo [Pacific Reef Heron (Egretta sacra (Gmelin))] fishing in shallow water, and getting close up, noticed that it had a kingfisher in company. Three times I saw the kingfisher dive into the shallow water after shrimps, then fly onto a rock to eat them.” [1]

So, what’s this somewhat strange account about?

There is indeed a possibility that the large Fijian Islands once harbored more than one kingfisher species, however, this particular account here pretty sure refers to the Collared Kingfisher, with the small species mentioned being the European Kingfisher (Alcedo atthis (L.)).

The whole account is expressed a bit unhappily, and this Mr. G. T. Barker very likely wasn’t a naturalist at all, that becomes very clear when he later also descibes a hummingbird that he had killed on the Fijian Island, and which in fact has been a honeyeater (Myzomela jugularis Peale) (his description, however, does not fully match that species, but that is another story ….).

*********************

References:

[1] Whitney South Sea Expedition of the American Museum of Natural History. Extracts from the journal of Rollo H. Beck. Vol. 2, Dec. 1923 – Aug. 1925

*********************

edited: 13.03.2020

The genus Pareudiastes – some thoughts about the Puna’e and its mysterious congeners

The genus Pareudiastes consists of two species that both are known from historical times, meaning ‘having been seen’ by western scientists. We can probably add at least two undescribed extinct forms that are known exclusively from scanty subfossil remains, one from Fiji and one from the Solomon Islands.

The two species of which at least skins remain are very little known, the puna’e (Pareudiastes pacificus Kubary, Hartlaub & Finsch) from Samoa is in fact the best known of them.

Depiction from: G. Hartlaub; O. Finsch: On a collection of birds from Savai and Rarotonga Islands in the Pacific. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1871: 21-32

(public domain)

***

The puna’e, whose name roughly translates as “springs up“, is known to have inhabited the rainforests of Savai’i, Samoa; it is said by the natives to have lived in burrows, which were longer than a man’s arm and which ended in a sort of chamber in which the bird slept during the day.

The large eyes of the species indeed point to a somewhat nocturnal habit.

When the bird was disturbed it jumped up from its burrow with fluttering wings but being flightless it landed shortly after and run away quickly.

It is furthermore known that it was not a vegetarian species, since it died when it was fed with plant material but was “happy” when fed with insects.

***

There is at least one reliable account that indicates that this species also inhabited the neighboring island of ‘Upolu.:

“The Samoans always speak of the Pareudiastes as the ‘bird which burrows like a rat.’ Again and again when I have put the question to a native, ‘Do you know the Puna’ e?’ the reply has been, ‘No, I have never seen it; but that is the bird of which the old people speak that it used to be very plentiful long ago, and that it burrows like a rat and lives underground.’ It is very rarely that I have met with any one who has seen the bird; but I have met with two persons who have actually taken it in its burrow. The first is a man well known to me, and in whose veracity I have faith. He says that about four years ago [ca. 1870] he was one of a large party hunting feral pigs in the mountains of Upolu, when they came upon a burrow which one of the party pronounced to be the hole of a Puna’e. My informant says that he put his arm into the hole, and at its extremity (which he could barely reach) he found the bird. He drew it out, and, taking it home, tried to tame and feed it; but it would not eat, and soon died.” [1]

Yet, how is this possible? The islands of Savai’i and ‘Upolu are separated by the 13 km wide Apolima strait.

Photo: Teineisavaii; Image Science and Analysis Laboratory, NASA-Johnson Space Center. “The Gateway to Astronaut Photography of Earth.”

(public domain)

***

During the Pleistocene, the sea level was lower and Manono very likely was connected with ‘Upolu, but Apolima was not, and Savai’i and ‘Upolu also weren’t connected.

So, how did a flightless bird manage to get from one island to the other?

The answer might be that the Puna’e wasn’t flightless at the time when the sea level was lower, or that the birds from ‘Upolu represented a distinct (sub)species.

***

What do we know about the second historical known species, the Makira Woodhen (Pareudiastes silvestris (Mayr))?

This species is known from a single specimen that was taken in 1929 on the island of Makira, Solomon Islands in montane forest at an elevation of about 600 m, only its skin was preserved, the bones not, and it apparently was flightless or at least nearly so.

The natives called it kia and hunted it with dogs.

That’s all.

The species was apparently still ‘well-known’ by the natives in 1953, and they also said that it was not rare, nevertheless not a single one was ever seen since (by western scientists).

The Makira Woodhen, or Kia, however, is the sole member of this genus that may in fact still survive, and I personally hope that it might be rediscovered someday.

***

The two additional forms are, as I’ve said before, known only from some scanty subfossil remains found on the island of Buka in the northernmost part of the Solomon Islands as well as on Viti Levu, the largest of the Fijian Islands respectively.

***

The genus Pareudistaes should be merged with the genus Gallinula, by the way.

*********************

References:

[1] Letter from Rev. S. J. Whitmee. In: Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1874: 183-186

*********************

edited: 04.07.2023