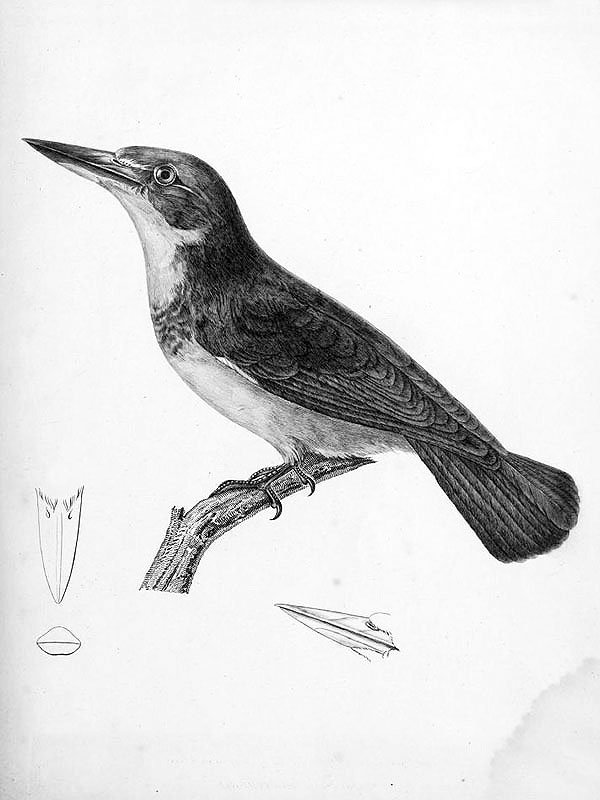

The Mangareva Kingfisher still is one of the most enigmatic birds I am aware of so far.

The species inhabited the Gambier Islands, and another species occurring 1000s of km to the northwest of it, the Niau Kingfisher (Todiramphus gertrudae Murphy), is still officially assigned to this bird as a subspecies.

I have desperately tried to find the original description of this species, and here it is.:

“Il existe, en effet, depuis longtemps dans les galeries du Muséum un Martin- pêcheur qui a été rapporté en 1841 de Mangarewa (archipel Gambier) par l’Astrolabe (Voyage au Pôle Sud) et qui répond exactement à la description et à la figure de l’Halcyon Reichenbachi. Cet oiseau a le sommet de la tête d’un roux qui va en s’éclaircissant et tire au blanc jaunâtre du côté, du front, mais qui est assez intense sur le vertex où se détachent quelques plumes vertes. Sur les oreilles il existe aussi, de chaque côté une tache verte, passant au noirâtre en arrière et tendant à rejoindre une bande noire qui fait le tour de l’occiput. Cette bande foncée limite en dessus un large collier blanc, un peu sali par quelques taches noires, qui se fond sur les côtés dans la teinte blanche qui couvre toutes les parties inférieures du corps, les flancs seuls offrant un peu de roux et encore sur des points cachés entièrement par les ailes. Celles-ci sont d’un vert légèrement bleuâtre, avec des lisérés roux très fins au bord des couvertures alaires. La queue est également d’un vert bleuâtre au milieu, d’un vert mélangé de grisâtre sous lespennes externes, qui sont d’ailleurs incomplètes. Enfin le bec est noir et la mandibule, inférieure blanche ou plutôt jaunâtre dans toute sa portion basilaire. Les pattes sont d’un m brun foncé. La longueur totale de l’oiseau est de 0,170; l’aile mesure 0,090, la queue 0,880, le bec 0,018; le tarse 0,014. Dès 1889, en faisant une revision des Alcédinidés du Muséum en vue de leur instal- lation dans les nouvelles galeries, j’avais désigné ce Martin-pêcheur de Mangarewa sous le nom d” Halcyon Gambieri; mais je n’en avais pas publié la description jusqu’à ce jour.” [1]

translation:

“For a long time, there has been a kingfisher in the galleries of the Museum who was brought back in 1841 from Mangarewa (Gambier Archipelago) by the Astrolabe (Journey to the South Pole) and who exactly corresponds to the description and the figure of Halcyon Reichenbachi. This bird has the top of the head red that brightens to yellowish white on the side of the forehead but is quite intense on the vertex where some green feathers stand out. On the ears there is also, on each side a green patch, passing blackish back and tending to join a black band that goes around the occiput. This dark band has a large white necklace on top, a little dirty with a few black spots, which is melting on the sides into the white hue that covers all the lower parts of the body, only the flanks offering a little russet and are, on some points, hidden entirely by the wings. These are a slightly bluish green, with very fine red rims at the edge of the wing coverts. The tail is also bluish green in the middle, of a green mixed with greyish under the outer feathers, which are also incomplete. Lastly, the beak is black, and the mandible underneath is white or rather yellowish throughout its base portion. The legs are of a dark brown. The total length of the bird is 0,170; the wing measures 0,090, the tail 0,880, the beak 0,018; Tarsus 0,014. As early as 1889, by making a revision of the Alcedinidae of the Museum with a view to their installation in the new galleries, I had designated this kingfisher of Mangarewa under the name of Halcyon Gambieri; but I had not published the description so far.“

***

What I am wondering about most is the fact that the Mangareva – and the Niau Kingfishers still are regarded to as a single species; on the other hand, both forms are rather similar to each other.

Which of the many other Polynesian islands might once have harbored their own kingfisher forms not known to us today?

*********************

*********************

[1] M. E. Oustalet: Les Mammifères et les oiseaux des iles Mariannes. Nouvelles archives du Muséum d’histoire naturelle 3(7): 141-228. 1895

[2] D. T. Holyoak; J. C. Thibault: Halcyon gambieri gambieri Oustalet, an extinct Kingfisher from Mangareva, South Pacific Ocean. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club 97(1): 21-23. 1977

*********************

edited: 08.08.2021