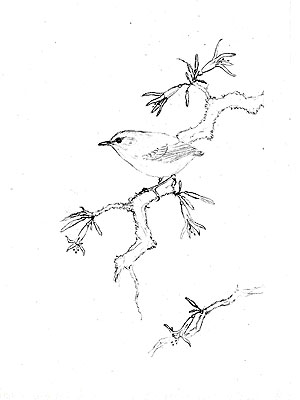

Der Grünschlüpfer ist mit ca. 8 cm Neuseelands kleinster Vogel und zugleich einer der urtümlichsten.

Derzeit werden dieser Art zwei Unterarten zugeordnet, die Nominatform, die auf der Südinsel lebt und die ssp. granti Mathews & Iredale (siehe Foto), die auf der Nordinsel vorkommt.

https://www.inaturalist.org/people/kevin_frank

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

*********************

Auf der Nordinsel weist die Art eine lückenhafte Verbreitung mit mehreren voneinander getrennten Populationen auf und lange Zeit wurde angenommen, dass dies durch Veränderungen der Umwelt durch menschliche Einflüsse hervorgerufen wurde – dem scheint aber nicht so zu sein. Eine Studie aus dem Jahr 2021 hat ergeben, dass es auf der Nordinsel mindestens drei genetisch voneinander unterscheidbare Populationen der Art gibt, von denen eine seit ca. 5 (südöstliche Küstenregion), eine weitere seit 2,5 bis 1,2 Millionen Jahren (Hauturu) genetisch isoliert sind. [1]

***

Es ist durchaus möglich, dass manche dieser genetisch isolierten Populationen den Status eigenständiger Unterarten zugeschrieben bekommen könnten, dafür sind aber weitere Untersuchungen notwendig, die auch die genetischen Daten der Nominatform von der Südinsel mit berücksichtigen.

*********************

Quelle:

[1] Sarah J. Withers; Stuart Parsons; Mark E. Hauber; Alistair Kendrick; Shane D. Lavery: Genetic divergence between isolated populations of the North Island New Zealand Rifleman (Acanthisitta chloris granti) implicates ancient biogeographic impacts rather than recent habitat fragmentation. Ecology and Evolution 2021; 00:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.7358

*********************

bearbeitet: 26.10.2022