Archaeopterygidae

Archaeopteryx albersdoerferi Kundrat et. al.

Archaeopteryx lithographica Meyer

Archaeopteryx siemensii Dames

*********************

edited: 20.12.2019

Archaeopterygidae

Archaeopteryx albersdoerferi Kundrat et. al.

Archaeopteryx lithographica Meyer

Archaeopteryx siemensii Dames

*********************

edited: 20.12.2019

Opisthocomidae

Hoazinavis lacustris Mayr et al.

Hoazinoides magdalenae Miller

Namibiavis senutae Mourer-Chauviré

Protoazin parisiensis Mayr & De Pietri

*********************

edited: 09.12.2019

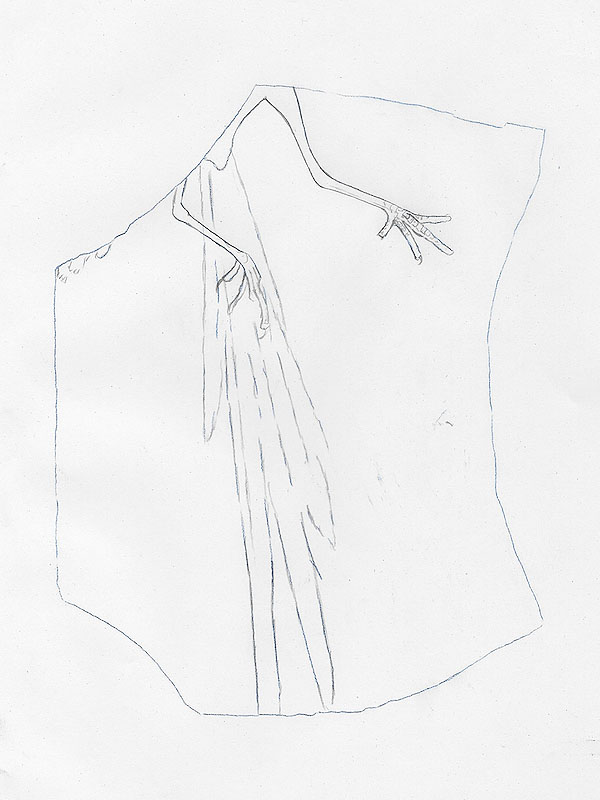

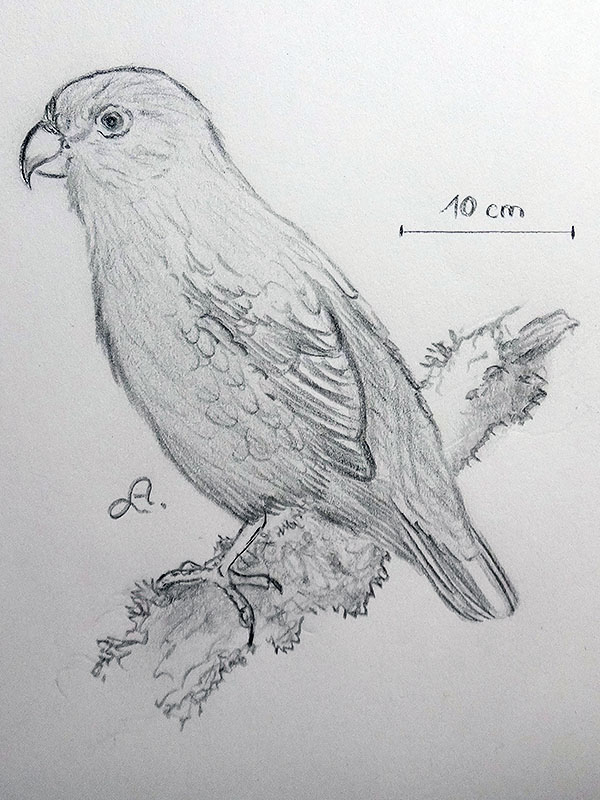

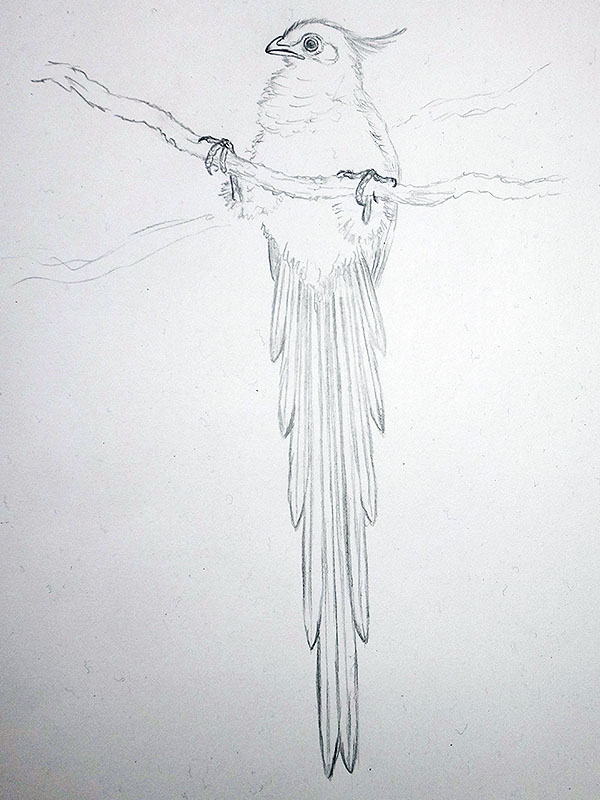

This is a small bird from the Eocene of Wyoming, USA, it was only about 10 cm long and is so far known from a complete skeleton with most of the feathers preserved as well.

The bird is not yet described but is apparently currently under study, it may turn out to be related to Morsoravis sedilis Bertelli, Lindow, Dyke & Chiappe, and to belong into a new family, probably named the Morsorornithidae or alike, which then again are perhaps somehow related to the mousebird/parrot/songbird ‘orbit’.

The reconstruction shows it while somewhat stretching its left wing, it was ‘fun’ to draw all this wing feathers, and I probably will do that NEVER EVER AGAIN!!! 😉

*********************

*********************

A little update here:

This bird is now apparently included into the genus Morsoravis. [2]

*********************

References:

[1] Lance Grande: The Lost World of Fossil Lake: Snapshots from Deep Time. University of Chicago Press 2013

[2] Daniel T. Ksepka; Lance Grande; Gerald Mayr: Oldest finch-beaked birds reveal parallel ecological radiations in the earliest evolution of passerines. Current Evolution 29(4): 657-663. 2019

*********************

edited: 07.12.2019

Protopterygidae

Protopteryx fengningensis Zhang & Zhou

*********************

edited: 07.12.2019

Family incertae sedis

Horezmavis eocretacea Nesov (?)

Gobipterygidae

Gobipteryx minuta Elzanowski

*********************

edited: 07.12.2019

This new bird has recently been reported from Argentinia, and its name apparently is taken from the Aonikenk language, which is or was spoken by the Mapuche of southern Argentinia and its translation is given in the title.

***

The new genus and species is known so far from a single bone, an incomplete right coracoid, whose „combination of characters strongly suggests anseriform affinities“. [1]

That means that this species obvioulsy was an anseriform, some duck- or goose-like bird, more or less similar to other Late Cretaceous or Early Paleocene species.

Let’s see if there will be more remains to be discovered in the future.

*********************

References:

[1] Fernando. E. Novas; Federico. L. Agnolin; Sebastián Rozadilla; Alexis M. Aranciaga-Rolando; Federico Brisson-Egli; Matias J. Motta; Mauricio Cerroni; Martín D. Ezcurra; Agustín G. Martinelli; Julia S. d ́Angelo; Gerardo Alvarez-Herrera; Adriel R. Gentil; Sergio Bogan; Nicolás R. Chimento; Jordi A. García-Marasà; Gastón Lo Coco; Sergio E. Miquel; Fátima F. Brito; Ezequiel I. Vera; Valeria S. Perez Loinaze; Mariela S. Fernández & Leonardo Salgado: Paleontological discoveries in the Chorrillo Formation (upper Campanian-lower Maastrichtian, Upper Cretaceous), Santa Cruz Province, Patagonia, Argentina. Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales, n. s. 21(2): 217-293. 2019

*********************

edited: 07.12.2019

Avisauridae

Avisaurus archibaldi Brett-Surman & Paul

Bauxitornis mindszentyae Dyke & Ősi

Concornis lacustris Sanz & Buscalioni

Enantiophoenix electrophyla Cau & Arduini

Gettya gloriae (Varrichio and Chiappe)

Halimornis thompsoni Chiappe, Lamb & Ericson

Intiornis inexpectatus Novas et al.

Mirarce eatoni Atterholt et al.

Neuquenornis volans Chiappe & Calvo

Soroavisaurus australis Chiappe

*********************

edited: 06.12.2019

***

Note that this order may not be valid.

This tiny thing could be called the „Cretaceous Nicobar Pigeon“, it had somewhat elongated neck feathers, the typical short tail, or rather a not-a-tail-at-all tail so typical for many of those strange Cretaceous enantiornithine birds that we now already know.

The strange-feathered creature comes from China, where it lived some 130 Million years ago in the late Early Cretaceous.

The genus name refers to its crural feathers (bird trousers) which are actually found in many birds, but here they are shaped like nothing ever seen before, maybe like a thin sheet of ceratin with a chewed end, or brush-like end, not at all like a feather. The species name again refers to its multi-toothed beak.

*********************

The bird reached a size of about 10 to maybe 11 or 12 cm when fully grown. The body feathers appear to have been more hair- than feather-like, and they may have been dark, while those on its neck were somewhat elongated and apparently were even glossy [1] … why not.

***

Unfortunatly I could not find any plant species from the same place and time.

*********************

References:

[1] Min Wang; Jingmai K. O’Connor; Yanhong Pan; Zhonghe Zhou: A bizarre Early Cretaceous enantiornithine bird with unique crural feathers and an ornithuromorph plough-shaped pygostyle. Nature Communications 8: 1-12. 2017

*********************

edited: 19.11.2019

This tiny bird is thought to be the ancestor of the kingfishers or of the todies, or of both.

Quasisyndactylus longibrachis was very small, only about 10 cm long, its legs were quite long, very much like in today’s todies (Todidae) and its feet were syndactyl (that means two of the toes, toes 3 and 4, are fused together), like those of all known Coraciiformes showing that it was a member of that order.

The species is known from several specimens, some of which also still harbor their feathering, showing that this species had rather roundish wings and a rather long tail.

*********************

References:

[1] G. Mayr: „Coraciiforme“ und „piciforme“ Kleinvögel aus dem Mittel-Eozän der Grube Messel (Hessen, Deutschland). Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg, Band 205. 1998

*********************

*********************

*********************

edited: 05.11.2019; 06.11.2019

Here I want to write a bit about two enigmatic birds that allegedly both were collected in Africa at the beginning of the 19th century; these are Adanson’s Bee-eater and Latreille’s Bee-eater.

*********************

Adanson’s Bee-eater is an enigmatic bird known only from a single specimen which is commonly thought to have been an artificially specimen, assembled from several bird parts, a practice that was rather common in these olden days when collectors were keen to have in their collections the most rare exhibition pieces.

The following French texts are all from François Le Vaillant, they describe this ’species‘ and give us some additional information about its wehereabouts. [1]

„Ce guêpier à queue en flèche ayant été méconnu par Buffon qui l’a, donné comme une simple variété de climat de son guêpier marron et bleu, ou de l’Isle-de-France, espèce que nous avons décrite dans notre précédent n°, sous la dénomination de guêpier Latreille, nous avons dû encore lui donner un nom distinctif, et nous ne pouvions à cet égard mieux faire, je pense, que de choisir celui du célebre voyageur qui l’ayant rapporté du Sénégal, l’a le premier fait connoître en Europe. Il suffira, je pense, de comparer les figures exactes que nous avons publiées de ces deux oiseaux, pour être d’abord et du premier coup-d’œil convaincu de la méprise de Buffon à leur égard, et être persuadé enfin qu’ils forment deux espèces très distinctes, bien loin de n’être l’un qu’une variété de l’autre; on ne conçoit même pas, en voyant les figures qui représentent dans les planches enluminées de Buffon ces deux oiseaux, l’un sous le nom de guêpier de l’Isle-de-France, n° 252, et l’autre, n° 314, sous celui de guêpier à longue queue du Sénégal, comment il a été possible de commettre cette erreur, et encore moins qu’elle ait été perpétuée par tous les ornithologistes qui ont écrit sur les oiseaux depuis Buffon. On conçoit en effet d’autant moins cette méprise, que ces deux figures, d’ailleurs très mauvaises , different bien plus l’une de l’autre encore, que ne différent réellement ces deux oiseaux eux-mêmes entre eux, mais assez cependant pour être bien sûr qu’ils ne peuvent être confondus ensemble comme appartenant à une seule et même espèce.„

translation:

„This spiny-tailed bee-eater was ignored by Buffon who gave it as a simple climate variety of its brown and blue bee-eater, or Isle-de-France [bee-eater], a species that we described in our previous issue. Under the denomination of Latreille, we have had to give it a distinctive name, and we could not, in this respect, have done better, I suppose, than the guide of the traveler who brought it back from Senegal, the first to make it known in Europe. It will suffice, I think, to compare the exact figures which we have published of these two birds, to be first and for the first glance convinced of Buffon’s mistake with regard to them, and to be finally persuaded that they form two very distinct species, far from being one variety of the other; it is not even conceivable, seeing the figures which represent, in the bright plates of Buffon, these two birds, one under the name of the Isle-de-France bee-eater, No. 252, and the other, No. 314, under that of long-tailed bee-eater from Senegal, how it was possible to make this mistake, let alone that it has been perpetuated by all the ornithologists who have written about birds since Buffon. This misunderstanding is all the less so conceived, that these two figures, which are, moreover, very bad, differ much more from one another than the two birds themselves really differ from one another, but enough, however, to be sure that they can not be confused as belonging to one and the same species.„

So, in short, these two birds were originally thought to be specifically identical, what they of course are not.

***

„Le guêpier Adanson est d’un tiers au moins plus fort que le guêpier Latreille, ainsi qu’on peut le voir d’ailleurs, en comparant les portraits de grandeur naturelle que nous en avons donné: il a le front ceint d’un large bandeau bleu qui, se prolongeant au-dessus des yeux, couvre les joues, les côtés et tout le devant du cou, la poitrine, et enfin tout le dessous du corps, en y comprenant les couvertures siqjéricures et inférieures de la queue, et le croupion; mais ce bleu s’affoiblit toujours davantage à mesure qu’il approche du bas-ventre; le dessus de la tête, à partir du bleu du front, ainsi que le derrière du cou, le manteau, les scapulaires, toutes les couvertures des ailes, et même les pennes de ces dernières, ainsi que toutes celles de la queue, sont couleur marron; seulement la partie excédante des deux pennes prolongées de la queue, ainsi que le bout des premières pennes des ailes, sont noirâtres; et les dernières plumes des ailes, proche le dos, sont en partie du même bleu que celui du dessous du corps; le bec est noir; les pieds sont bruns rougeàtres. Nous ignorons la couleur des yeux, n’ayant vu que la dépouille de cet oiseau, que je n’ai rencontré dans aucune des parties de l’Afrique dans laquelle j’ai pénétré; je n’ai même vu de cette espèce que le seul individu qu’en avoit rapporté Adanson du Sénégal, où il l’avoit recueilli durant ses voyages.„

translation:

„The Adanson bee-eater is at least a third stronger than the Latreille bee-eater, as can be seen elsewhere, by comparing the life-size portraits we have given: it has at its forehead a blue band which, extending above the eyes, covers the cheeks, the sides and all the front of the neck, the chest, and finally the whole underbody, including the undertail coverts of the tail, and the rump; but this blue becomes more and more feeble as it approaches the lower abdomen; the top of the head, from the blue of the forehead, as well as the back of the neck, the mantle, the scapulars, all the coverts of the wings, and even the feathers of these, as well as those of the tail, are colored brown; only the exceeding part of the two elongated feathers of the tail, as well as the end of the first primaries of the wings, are blackish; and the last feathers of the wings, near the back, are partly of the same blue as that of the underbody; the bill is black; the feet are reddish brown. We are ignorant of the color of the eyes, having seen only the remains of this bird, which I have not met in any part of Africa into which I have penetrated; I have not even seen of this species the only individual who had been brought back from Adanson of Senegal, where he had collected it during his travels.„

The author clearly states here that he did only see remains of this bird, but also that he did not see it at all, that is somewhat irritating to me.

But what was Adanson’s Bee-eater actually?

Well, the bird’s upper side looks almost exactly like that of the Southern Carmine Bee-eater (Merops nubicoides Des Mus & Pucheran) or the Northern Carmine Bee-eater (Merops nubicus Gmelin), the underside and forepart of the hea, however, come from another bird that, since the original specimen is now lost, will forever be unidentifiable.

*********************

Latreille’s Bee-eater, of which I won’t give any text because it isn’t really necessary, is said in its description to come from the Isle-de-France, known today as Mauritius but being far more widespread all over Africa. This ’species‘ might actually have been a Rufous-crowned Bee-eater (Merops americanus Statius Müller) or a Blue-throated Bee-eater (Merops viridis L.), both exclusively from Asia by the way. Again, the colors won’t fit completely, so again some parts of other birds might have been added to the depicted specimen. That was apparently a quite common practice in former times, the more rare and unique a specimen was the higher was its price ….

My personal conclusion is that both these ’species‘ never have existed.

*********************

References:

[1] François Le Vaillant: Histoire naturelle des promerops, et des guêpiers: faisant suite à celle des oiseaux de paradis par la même. A Paris, chez denné le jeune, Libraire, Rue Vivienne, N° 10. 1807

*********************

edited: 05.11.2019

Dieser tahitianische Papagei ist einer meiner Lieblingsvögel, leider existiert er aber nicht mehr da er durch eingeschleppte Säugetiere (Hunde, Katzen, Ratten) ausgerottet wurde.

Hier möchte ich zwei Darstellungen zeigen, die ich noch nicht kannte; beide stammen aus dem Jahr 1792 und wurden von Mitgliedern der Besatzung der HMS Providence angefertigt, die mit der Mission nach Tahiti gekommen war, Brotfruchtbäume und anderes botanisches Material vom Pazifik zu den Westindischen Inseln zu transportieren.

*********************

*********************

*********************

bearbeitet: 27.10.2019

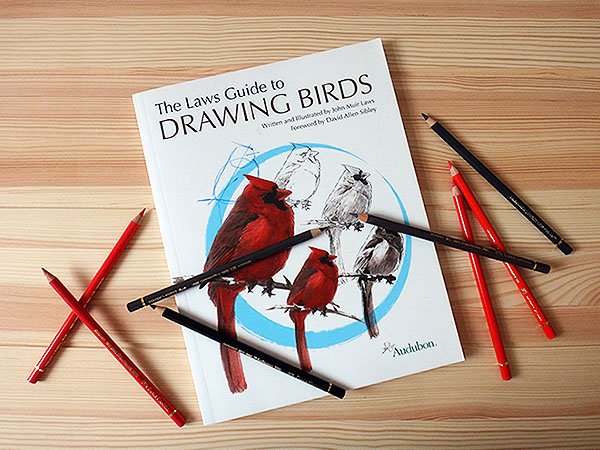

Christopher Kemp: Die verlorenen Arten: Große Expeditionen in die Sammlungen naturkundlicher Museen. Verlag Antje Kunstmann GmbH 2019

Well, what a book …!

I found this little treasure in an actual bookstore, a rare event these days ….

The author has done a lot of very, very good work, he visited several museums all over the world, and almost like a journalist (but a good one), he also interviewed several scientists to gain information about their respective „obsessions“, some of them are interested in – and specialzed to a special genus of frogs only etc..

The museums all over the world still keep giant collections, some more than 100 years old, that no one has ever seen, let alone catalogized or researched, and, due to job cuts and neglected financing, some of these hidden treasures are now literally crumbling to dust. There are some few scientists who take the challenge to research the sheer ammount of items while revising a special genus of insects or of any other animal or plant etc., and while doing so they almost always discover new species, many of which are already extinct in the localities where they were collected hundreds of years ago.

The book shows us that many museums are treasure troves full of undiscovered biodiversity that need far more attention by the public, and tells the stories of their discoveries, from the first collection to the latest state of things.

I can only recommend this book!

***

This book is also available in English: „The Lost Species: Great Expeditions in the Collections of Natural History Museums“.

*********************

edited: 27.10.2019

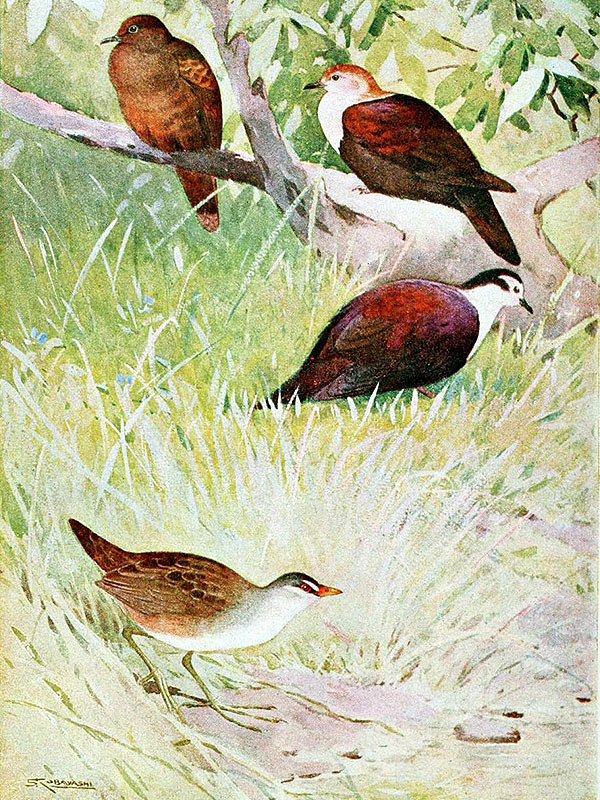

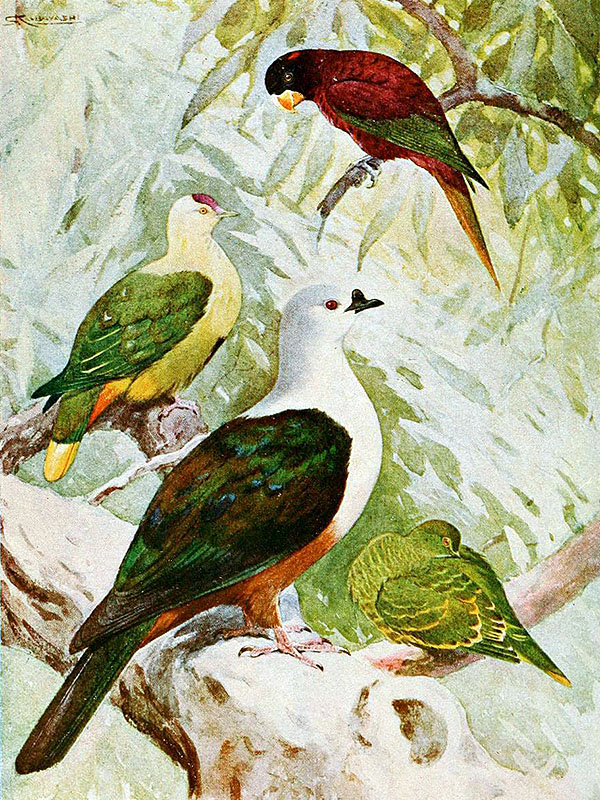

A while ago I found this Japanese book about the birds of Micronesia online while searching for I don’t no what, it originally probably included more than these three plates, however, these are the only ones that I could find and I want to share them here because they are so exceedingly beautiful.:

Tokutaro Momiyama: Horyo Nanyo Shoto-san chorui. Tokyo: Nihon Chogakkai: Taisho 11. 1922

(public domain)

***

I will name the birds with their current names in the order in which they are depicted.

*********************

*********************

edited: 20.10.2019

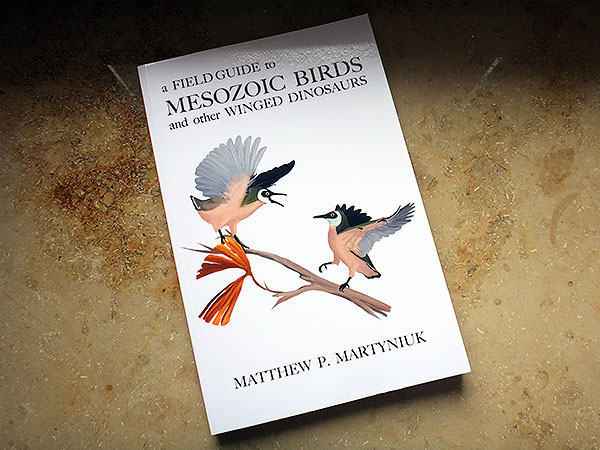

Matthew P. Martyniuk: A Field Guide to Mesozoic Birds and Other Winged Dinosaurs. Pan Aves 2012

*********************

Ich habe dieses Buch schon ein paar Monate, und ich muss gestehen, ich weiß nicht recht wie ich es einordnen soll.

Die Idee des Autors war es, sein Buch wie einen herkömmlichen Field Guide, ein Bestimmungsbuch für unterwegs, aufzubauen und genau das ist ihm auch gelungen. Das Buch umasst hierbei alles was im Mesozoikum gelebt hat und (sowohl wahrscheinlich wie auch tatsächlich) Federn besessen hat (nicht alles davon würde heutzutage als Vogel durchgehen).

In der Einleitung erfährt man, was genau ein Vogel ist, oder, anders ausgedrückt, wie weit man diesen Begriff dehnen kann (… alles was Federn hat ….). Es folgen einige Informationen über den Ursprung der Vögel, den Ursprung der Federn und, vor allem, ein kleiner Überblick über die Vielfalt, die innerhalb dieser Tiergruppe bereits im Mesozoikum geherrscht hat.

Fast jede der vorgestellten Arten ist mit einer Abbildung versehen, die jeweils auf aktuellen wissenschaftlichen Erkenntnissen beruht, weshalb man sich nicht wundern darf, dass die allermeisten Abbildungen eher weniger farbenfroh ausfallen (“Carotinoids be damned” schreibt der Autor hierzu schon als Vorwort).

Ich kann dieses Buch nur empfehlen! 😛

*********************

bearbeitet: 20.10.2019

Der Einfarb-Ameisenpitta ist ein mehr oder weniger völlig schlicht, rötlich gefärbter, typischer Ameisenpitta, der in den dichten Wäldern der Anden und ihrer Ausläufer von Nordbolivien bis in Teile Südvenezuelas lebt.

Der Vogel erreicht eine Größe von etwa 14,5 bis 15 cm.

Die Art ist in sechs Unterarten unterteilt, die nun alle auf den Artstatus hochgestuft werden sollen. Sie werden dann wahrscheinlich wie folgt benannt:

Bolivianischer Ameisenpitta (Grallaria cochabambae J. Bond & Meyer de Schauensee)

Cajamarca-Ameisenpitta (Grallaria cajamarcae (Chapman))

Junín-Ameisenpitta (Grallaria obscura Berlepsch & Stolzmann)

Einfarb- oder Muisca-Ameisenpitta (Grallaria rufula Lafresnaye)

Sierra Nevada-Ameisenpitta (Grallaria spatiator Bangs)

Urobamba-Ameisenpitta (Grallaria occabambae (Chapman))

Diese zukünftigen neuen Arten unterscheiden sich geringfügig im Farbton ihres rötlich gefärbten Gefieders, höchstwahrscheinlich jedoch eher in ihrer DNA.

*********************

*********************

bearbeitet: 18.04.2024

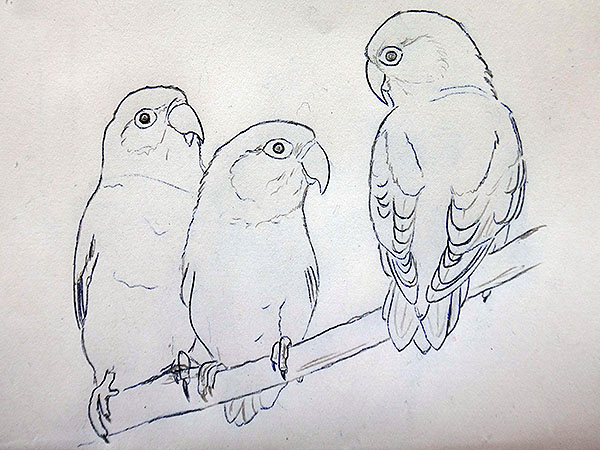

Heracles inexpectatus, the unexpected Hercules, is a fossil parrot from the St. Bathans fossil site in New Zealand, that just has been described. [1]

The species is known from only two remains, or rather remains of remains to be more precicely, these are a partial left tibiotarsus and a partial right tibiotarsus, that’s just all. The species can be reconstructed as having reached a size of around 1 m, making it the largest known parrot species, dead or alive.

***

Unfortunately, one of the authors of this remarkable species apparently seem to think that the new find isn’t appetizing enough for the press, so added a „fierce beak“ to the description and is even speculating that this species, because of it’s size, must have been a predatory bird, which, of course, is complete bullshit.

According to the paper, the species apparently was a member of the Nestoridae, a family of parrots endemic to New Zealand, and within this family its closest relative appears to be the Kakapo (Strigops habroptilus Grey), a strict herbivor. So, I personally have no idea why one of the authors does such silly speculations.

Whatsoever … there was once a giant parrot rumbling the forests of New Zealand around 19 Million years ago, and that is remarkable enough, at least for me.

*********************

References:

[1] Trevor H. Worthy; Suzanne J. Hand; Michael Archer; R. Paul Scofield; Vanessa L. De Pietri

*********************

I need to write some kind of update here since the British- but also the German press apparently need to call this new species a “Cannibal” and a “Horror-Papagei”, and even claim that some scientist allegedly has suggested that this parrot was eating its smaller conspecific mates.

What a big load of shit, let’s say it together: “SHIT!!!” Which fucking scientist, as they claim, has ever said such a bullshit???

This was, and I bet my left hand for that, a large kakapo, nothing but a harmless, flightless, vegetarian creature, and the press apparently degenerates more and more to a shitpot full of idiots and arseholes.

Many Thanks!

*********************

edited: 08.08.2019

This species was described in 2010, it is known from five or six specimens found in the Messel shale, five of which include cervical vertebrae which again all bear strange small tubercles unknown in any other bird dead or alive.

The bird may or may not be related to the so-called screamers (Anhimidae), it had a quite small head compared to its body and had very large and strong wing bones, thus apparently was good at flying, its feet have short toes which appear to have been somewhat flattened – and my gut feeling tells me that they may have had been webbed ….

*********************

*********************

edited: 07.08.2019

Familie incertae sedis

Elaphrocnemus brodkorbi Milne-Edwards

Elaphrocnemus crex Milne-Edwards

Elaphrocnemus phasianus Milne-Edwards

Gradiornis walbeckensis Mayr

Itaboravis elaphrocnemoides Mayr et al.

Lavocatavis africana Mourer-Chauviré et al.

Ameghinornithae

Ameghinornis minor Gaillard

Ameghinornithidae gen. & sp. ‘Jebel Qatrani Formation, Ägypten’

Ameghinornithidae gen. & sp. ‘Nei Mongol, China’

Strigogyps dubius Gaillard

Strigogyps robustus (Lambrecht)

Strigogyps sapea (Peters)

Strigogyps sp. ‘Eckfelder Maar, Deutschland’

Bathornithidae

Bathornis celeripes Wetmore

Bathornis cursor Wetmore

Bathornis fricki Ostrom

Bathornis geographicus Wetmore

Bathornis grallator Olson

Bathornis veredus Wetmore

Eutreptornis uintae (Cracraft)

Paracrax antiqua Shufeldt

Paracrax gigantea Cracraft

Paracrax wetmorei Cracraft

Cariamidae

Cariama santacrucensis Noriega et al.

Cariamidae gen. & sp. ‘Alto Río Bandurrias, Chile’

Chunga incertis (Tonni)

Noriegavis santacrucensis (Noriega et al.)

Riacama caliginea Ameghino

Idiornithidae

Dynamopteris boulei Gaillard

Dynamopterus gaillardi (Cracraft)

Dynamopterus gallicus (Milne-Edwards)

Dynamopterus gracilis Milne-Edwards

Dynamopterus minor (Milne-Edwards)

Dynamopterus velox Milne-Edwards

Gypsornis cuvieri Milne-Edwards

Oblitavis insolitus Mourer-Chauviré

Occitaniavis elatus (Milne-Edwards)

Propelargus cayluxensis Lydekker

Propelargus olseni Brodkorb

Phorusrhacidae

Andalgalornis steulleti (Kraglievich)

Andrewsornis abbotti Patterson

Devincenzia pozzii (Kraglievich)

Eleutherornis cotei Gaillard

Hermosiornis australis Moreno

Kelenken guillermoi Bertelli, Chiappe & Tambussi

Llallawavis scagliai Degrange et al.

Mesembriornis incertus Rovereto

Mesembriornis milneedwardsi Moreno

Paleopsilopterus itaboraiensis Alvarenga

Paraphysornis brasiliensis (Alvarenga)

Patagornis marshi Moreno & Mercerat

Phorusrhacos longissimus Ameghino

Physornis fortis Ameghino

Procariama simplex Rovereto

Psilopterus bachmanni (Moreno & Mercerat)

Psilopterus lemoinei (Moreno & Mercerat)

Psilopterus affinis (Ameghino)

Psilopterus colzecus Tonni & Tambussi

Titanis walleri Brodkorb

Salmilidae

Salmila robusta Mayr

Salmilidae gen. & sp. `Green River Formation, USA`

*********************

edited: 24.04.2024

This species was described in 2017, it is one of the many birds from the Messel shale, that are somehow related to living ones but on the other hand again … are completely different.

This one is thought to be related to the Charadriiformes, and it may indeed have been a member of the jacana family (Jacanidae).

*********************

*********************

BTW: I only recently learned that the age of the Messel shale spans from the upper Early – to the lower Middle Eocene.

So not every bird from there is from the Middle Eocene.

*********************

edited: 04.08.2019

Dieser rätselhafte Vogel aus dem späten Paläozän frühen Eozän Brasiliens ist nur von einem einzigen, zerbrochenen Tarsometatarsus bekannt, der jedoch offenbar den Kuckucken zugeordnet werden kann.

Ich kann nicht so viel über diesen Vogel sagen, er scheint für eine paläozäne Vogelart ziemlich groß gewesen zu sein, und es könnte tatsächlich ein echter Kuckuck gewesen sein oder es könnte etwas völlig anderes gewesen sein.

***

Ein kleines (längst überfälliges) update … diese Art wird mittlerweile mit der Familie Gracilitarsidae in Verbindung gebracht.

Der Vogel in meiner neuen Rekonstruktion ist immer noch ungefähr 15 cm lang und ungefähr ein Drittel größer als Gracilitarsus mirabilis Mayr, der einzigen anderen bekannten Art der Familie.

*********************

bearbeitet: 28.07.2019

Es dürfte schon aufgefallen sein, dass ich ein bisschen von den Vögeln des Paläozän besessen bin, auch weil wir jede Menge gar nichts über sie wissen, besonders über jene aus dem frühen Paläozän, dem Beginn der “T-Zeit”, der Zeit unmittelbar nach dem K T-Grenze.

Nun, es gibt eine neue Veröffentlichung, die einen Überblick über die Vögel gibt, die genau zu dieser Zeit existierten, an der K/T-Grenze … auf dem Kontinent der Antarktis, um genauer zu sein, aber auch über diese Zeit hinaus bis zum Oligozän. [1]

***

Ich habe diese Veröffentlichung noch nicht vollständig gelesen, aber da fast alle Vogelfossilien aus diesem Gebiet auf einzelne Knochen oder manchmal Teilskelette beschränkt sind, wirft es nicht so viel neues Licht auf die vorherigen Aufzeichnungen.

*********************

Quelle:

[1] Carolina Acosta Hospitaleche; Piotr Jadwiszczak; Julia A. Clarke; Marcos Cenizo: The fossil record of birds from the James Ross Basin, West Antarctica. Advances in Polar science 30(3): 250-272. 2019

*********************

bearbeitet: 25.07.2019

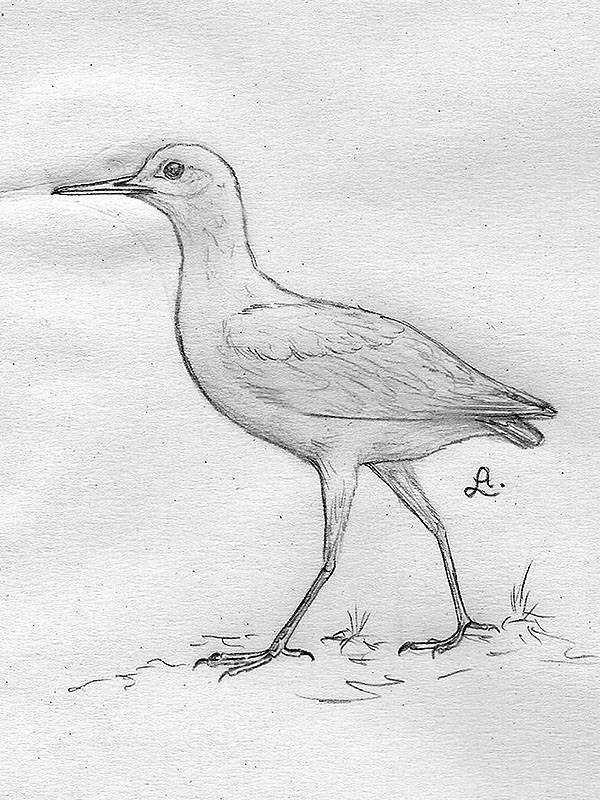

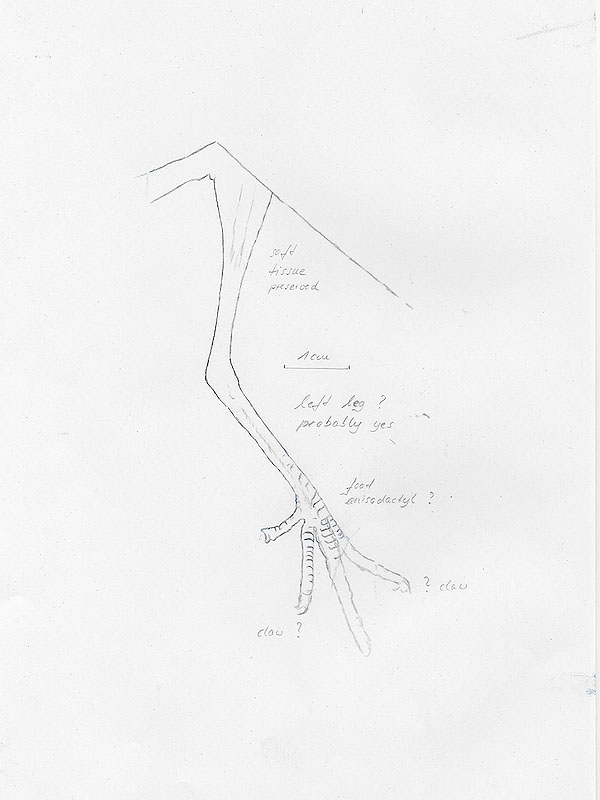

MNT-11-7952 ist ein bemerkenswertes Fossil eines rätselhaften Vogels mit einer außergewöhnlichen Erhaltung; Abdrücke der erhaltenen Schwanzfedern weisen einen bläulich grauen Farbton auf, die Beine und Füße zeigen noch Spuren ihres Weichgewebes.

Dies ist jedoch alles, was bisher bekannt ist. Die beiden Platten enthalten nichts als den Arsch, sorry, den Rumpf, die Beine und die Schwanzfedern.

Die Federn sind sehr lang und schmal und erinnern an die Schwanzfedern der rezenten Mausvögel (Coliiformes). Die Füße scheinen jedoch anisodaktyl (drei Zehen nach vorn, eine nach hinten gerichtet) zu sein, im Gegensatz zu allen bekannten Mausvögeln, ausgestorben oder noch lebend.

Das Fossil stammt aus dem mittleren Paläozän, ist also 60 bis 61 Millionen Jahre alt, und meiner Meinung nach könnte es sich tatsächlich um einen coliiformen Vogel handeln.

*********************

Hier ist ein kleiner skizzenhafter Versuch, diesen Vogel zu rekonstruieren, der, einschließlich seiner fast 20 cm langen Schwanzfedern, möglicherweise eine Gesamtlänge von ca. 34 cm erreicht haben dürfte, was sehr gut im Größenbereich moderner Mausvögel liegt!

*********************

Quelle:

[1] Gerald Mayr; Sophie Hervet; Eric Buffetaut: On the diverse and widely ignored Paleocene avifauna of Menat (Puy-de-Dôme, France): new taxonomic records and unusual soft tissue preservation. Geological Magazine: 1-13. 2018

*********************

bearbeitet: 24.07.2019

Ein neuer wissenschaftlicher Bericht [1] wurde gerade veröffentlicht, in dem mehrere neue Vogelreste beschrieben werden, leider ohne eine Art zu beschreiben, da diese Überreste einfach zu fragmentarisch sind. Die Überreste selbst stammen aus dem mittleren Paläozän Belgiens und aus dem späten Paläozän Frankreichs.

Es gibt einen sehr kleinen Gastornis sp., einen Lithornithiden, einen Ralloiden und einen nicht zuweisbaren „höheren Landvogel“, alle aus Belgien, und es gibt einen weiteren Lithornithiden, einen Pelagornithiden, einen möglichen Leptosomatiformen und einen wahrscheinlichen Cariamaformen, alle aus Frankreich.

Nun, und das ist eigentlich auch schon fast alles.

*********************

Quelle:

[1] Gerald Mayr; Thierry Smith: New Paleocene bird fossils from the North Sea Basin in Belgium and France. Geologica Belgica 22(1-2): 35-46. 2019

*********************

bearbeitet: 21.07.2019

Enantiophoenix electrophyla Cau & Arduini from the Late Cretaceous of Lebanon, roughly the size of a recent European Starling.

*********************

This species is known from parts of a foot and some very few further remains.

********************

References:

[1] Andrea Cau & Paolo Arduini: Enantiophoenix electrophyla gen. et sp. nov. (Aves, Enantiornithes) from the Upper Cretaceous (Cenomanian) of Lebanon and its phylogenetic relationships. ATTI della Società Italiana di Scienze Naturali e del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Milano 149(2): 293-324. 2008

*********************

edited: 14.07.2019

Elektorornis chenguangi Xing, O’Connor, Chiappe, McKellar, Carroll, Hu, Bai & Lei, a bird from the Cretaceous era described just now.

*********************

This bird is known only by a single leg with an unusually elongated middle toe and parts of the wing.

I will come back to that bird somewhat later ….

*********************

References:

[1] Lida Xing; Jingmai K. O’Connor; Luis M. Chiappe; Ryan C. McKellar; Nathan Carroll; Han Hu; Ming Bai; Fuming Lei: A new enantiornithine bird with unusual pedal proportions found in amber. Current Biology 29: 1-6. 2019

*********************

edited: 12.07.2019

Podicipedidae

Aechmophorus elasson Murray

Miobaptus huzhiricus Zelenkov

Miobaptus walteri Švec

Miodytes serbicus Dimitreijevich, Gál & Kessler

Pliolymbus baryosteus Murray

Pliolymbus lanquisti Brodkorb

Podicepidae gen. & sp. ‘Truckee A’

Podicepidae gen. & sp. ‘Truckee B’

Podiceps oligocaenus (Shufeldt)

Podiceps arndti Chandler

Podiceps caspicus (Habizl)

Podiceps csarnotatus Kessler

Podiceps discors Murray

Podiceps dixi Brodkorp

Podiceps miocenicus Kessler

Podiceps oligocaenus (Shufeldt)

Podiceps parvus (Shufeldt)

Podiceps sociata (Navás)

Podiceps solidus Kuročkin

Podiceps subparvus (Miller & Bowman)

Podilymbus mujusculus Murray

Podylimbus wetmorei Storer

*********************

edited: 01.07.2019

*********************

bearbeitet: 29.06.2023

*********************

bearbeitet: 23.06.2019

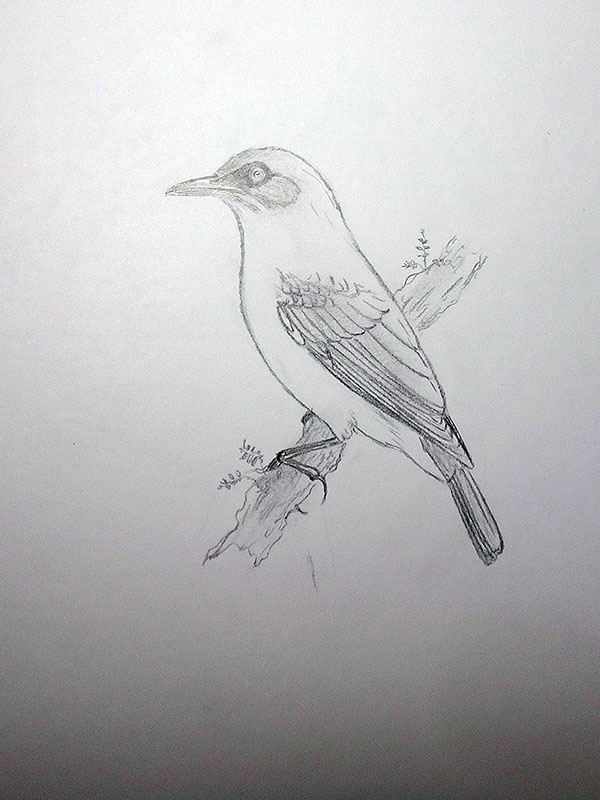

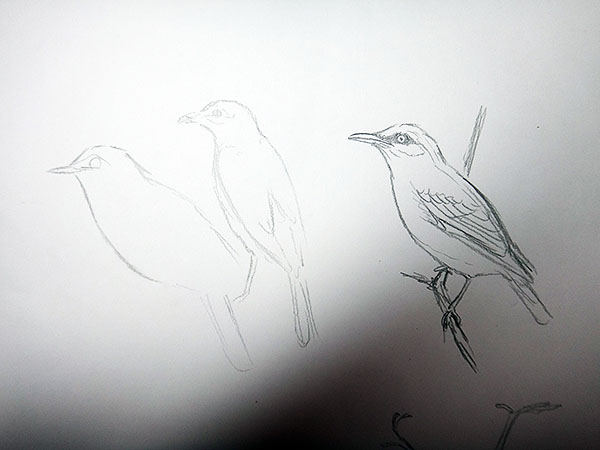

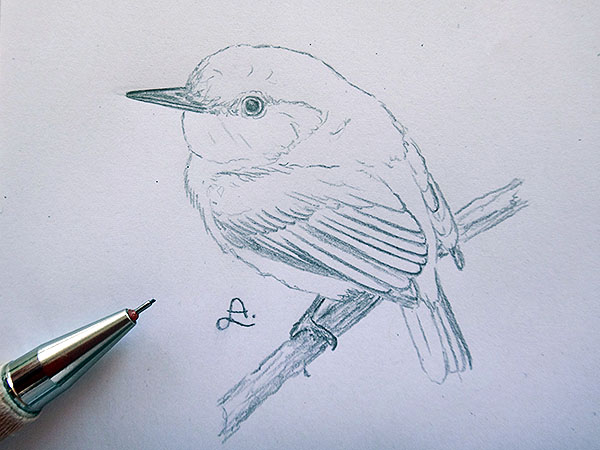

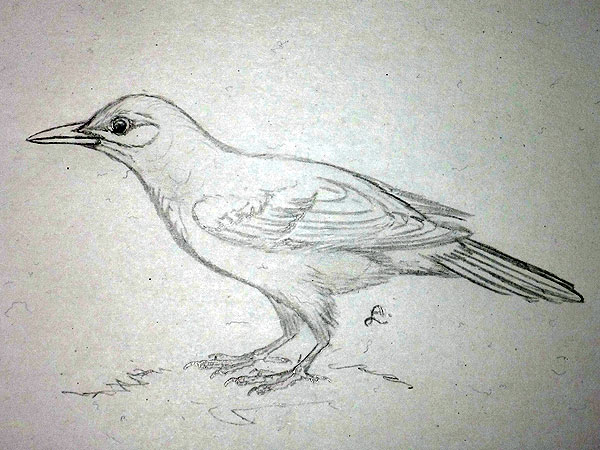

Today, I doodled some birdies, Rarotonga Starlings.:

Personally, I like these freehand sketches better, at least the bird on the right, because it looks more lively and less static. :

*********************

edited: 12.06.2019

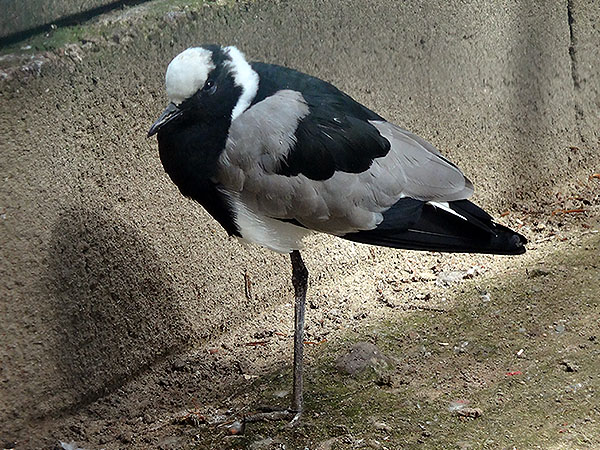

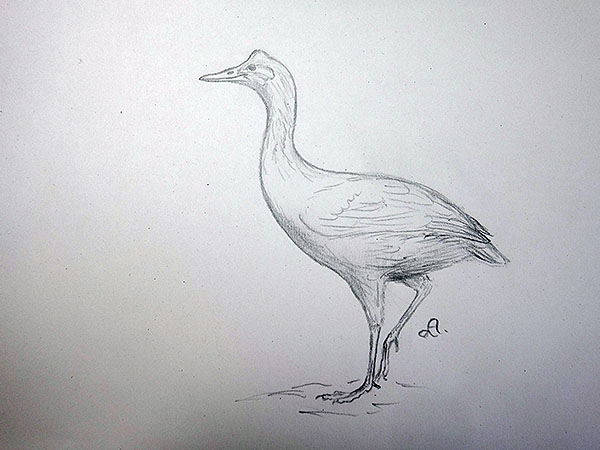

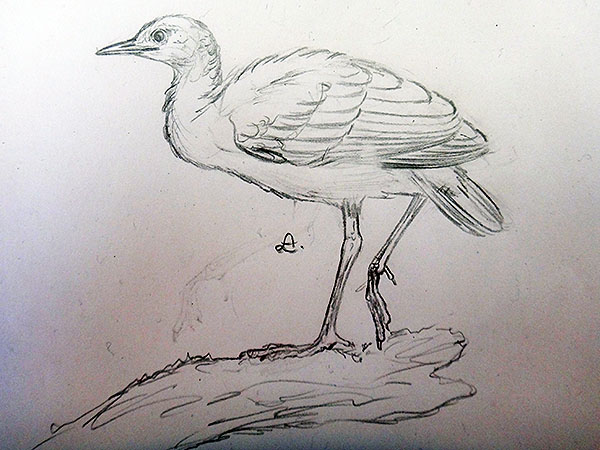

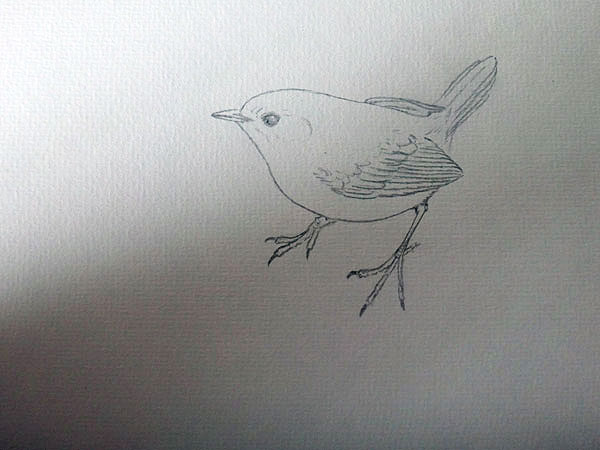

We were in the little zoo in Gotha today where we go almost once a year, and for the first time I took my sketchbook with me, which, however, wasn’t a great idea since there were way too many people and I could not really take the time to sketch something beside that one.:

*********************

… it’s a Blacksmith Lapwing (Vanellus armatus)

*********************

edited: 10.06.2019

Otididae

Chlamydotis mesetaria Sánchez Marco

Gryzaja odessana Zubareva

Ioriotis gabunii Burchak-Abramovich & Vekua

Miootis compactus Umanskaya

Otis affinis Lydekker

Otis bessarabicus Kessler & Gál

Otis hellenica Boev, Lazaridis & Tsoukala

Otis khozatzki ssp. beremendensis Jánossy

Pleotis liui Hou

*********************

Quelle:

[1] Zlatozar Boev; Georgios Lazaridis; Evangelia Tsoukala: Otis hellenica sp. nov., a new Turolian bustard (Aves: Otididae) from Kryopigi (Chalkidiki, Greece). Geologica Balcanica 42(1-3): 59-65. 2013

*********************

edited: 25.04.2024

Oh well, I did some research, and actually still do … here are the results I got so far.:

The first account dates from November 30th, 1895 and is given by a Dr. Georg Irmer, who was the Imperial German Government District Administrator in the Marshall Islands, which were a German overseas colony back then.

In his account he gives a bit information of some birds he saw when he inspected the Taongi Atoll (now Bokok) to collect guano samples for analysis and to reaffirm the German claim to the island, he mentions seabirds and a large ground-dwelling bird which he named a ‘Trappe‘, the German term for a bustard. He gives no further description or whatsoever, but it is thought that he might not have seen any of the birds commonly known from the Marshall Islands because neither he nor his Marshallese crew were able to identify that bird.

Given his name for the bird, ‘Trappe‘, it is quite likely that he indeed saw a rail of the genus Gallirallus, very much like the one that once inhabited the Wake Atoll to the north of the Marshall Islands. [4]

***

The second account comes from the natives of the Marshall Islands and was forwarded by them to the German ‘anthropologists’ who explored these islands at the beginning of the 20th century.

It is a bird named as the anang-, annan-, or annang. This is said to have been a very small bird (the size of a butterfly (!)), and to have possessed a pleasant smell, it is said to have lived among the rocks around the shores of the northern Marshall Islands. The bird is known from oral traditions at least from the Jaluit-, and the Wotho Atoll, and it is always said to have been a ground-dwelling singing bird.

This may in fact be a description of a Turnstone (Arenaria interpres (L.)), a species that winters in Micronesia and that was very much appreciated, for example by the inhabitants of Nauru, who cought them not to eat them but to tame them and keep them as pets.

Or it is the description of a small crake or a reed-warbler, mixed with some phantastic components. [4]

***

The third account comes from Paul Hambruch, a German ethnologist that researched the life of the natives of the island of Nauru, his accounts are merely stories that were told him by a native named Auuiyeda, and which he translated into German.

Let’s read them.:

“Es gibt auch Vögel auf Nauru, wie Fregattvogel, schwarze Seeschwalbe, weiße Seeschwalbe, Regenpfeifer, Brachvogel, Möve, Schnepfe, Uferläufer, Ralle, Lachmöve und Rohrdrossel.” [1]

translation:

“There are also birds on Nauru, as frigate bird, black tern, white tern, plover, curlew, gull, snipe, sandpiper, rail, black-headed gull and reed thrush.“

And he goes on.:

“Die Vogelwelt ist nach Zahl und Art reicher. Der Fregattvogel (Tachypetes aquila), itsi, die schwarze Seeschwalbe (Anous), doror, die weiße Seeschwalbe (Gygis), dagiagia, werden als Haustiere gehalten; der erste galt früher als heiliger Vogel, mit den beiden anderen werden Kampfspiele veranstaltet. Am Strande trifft man den Steinwälzer (Strepsilas interpres), dagiduba, den Regenpfeifer (Numenius), den Uferläufer (Tringoides), ibibito, die Schnepfe, ikirer, den Brachvogel ikiuoi, den Strandreiter iuji, die Ralle, earero bauo und zwei Möwenarten (Sterna), igogora und ederakui.

Im Busche beobachtet man an den Blüten der Kokospalme den kleinen Honigsauger raigide, die Rohrdrossel (Calamoherpe syrinx), itirir und den Fliegenschnäpper (Rhipidura), temarubi.” [1]

translation:

“The bird world is richer by number and species, The frigate bird (Tachypetes aquila), itsi, the black tern (Anous), doror, the white tern (Gygis), dagiagia, are kept as pets; the first one was formerly considered a holy bird, with the two others are used for fighting games. At the beach one mets with the turnstone (Strepsilas interpres), dagiduba, the plover (Numenius), the sandpiper (Tringoides), ibibito, the snipe, ikirer, the curlew, ikiuoi, the beach rider [?] iuji, the rail, earero bauo and two gull species (Sterna), igogora and ederakui.

In the bush one observes on the flowers of the coconut palm the small honeyeater raigide, the reed thrush (Calamoherpe syrinx), itirir and the flycatcher (Rhipidura), temarubi.“

The author is usually thought to have misinterpreted the things he was told by Auuiyeda, but I personally doubt that somehow, all the mentioned landbirds make in fact sence for georaphical reasons, so, why not?

Nauru is now almost deserted, the whole island looks like a building site – and it actually is one! There are some sad rests of the forest that once covered the whole island, and indeed some landbirds still manage to survive in small numbers, one of them, the Nauru Reed-Warbler (Acrocephalus rehsei (Finsch)) is even an endemic species, there’s no reason not to accept the former presense of a fantail, a honeyeater, and especially a rail, no reason at all!

These birds, especially the rail, may already have been extirpated by the beginning of the 20th century, leaving only memories and storys told by the islanders.

***

And last but not least, here the fourth account of birds from the Namoluk Atoll, Chuuk, that were enumerated by Max Girschner, another German who had lived in Micronesia at the beginning of the 20th century, he was a colonial offical, a doctor, and an ethnologist.

I have no access to his accounts, but I can give you quotations of them by Mac Marshall from 1971, here they are.:

“Ponape Lory (no Namoluk name)

Trichoglossus rubiginosus

Extinct breeder.

According to Girschner (1912:126), this species was blown to Namoluk in a typhoon in 1905, and apparently it still occurred on the atoll at the time of his visit. there are no lories at present on Namoluk nor can anyone alive on the atoll in 1971 remember seeing them.” [2]

According to Donald W. Buden this whole information is unlikely, and if these parrots have ever occurred on the Namoluk Atoll at all, they must have been brought there by people. [3]

I personally think … why not, typhoons may indeed blow parrots from one island to another, or how did the loris themselves came to end up on the island of Pohnpei in the first place?

But wait, there’s more.:

“A second bird mentioned by Girschner that no longer is found on Namoluk is “a small black and white bird” for which he gives the name lipukepuk.” [2]

The author states that this can only be the description of a New Hanover Mannikin (Lonchura (hunsteini ssp.) nigerrima (Rothschild & E. J. O. Hartert)), which does not occur anywhere in Micronesia and which is not black and white by the way. The bird he is actually referring to is Hunstein’s Mannikin (Lonchura hunsteini ssp. minor (Yamashina)), which again is very well occuring in Micronesia, at least on the island of Pohnpei (yes, again), and which is at least blackish and greyish ….

To me the whole account sounds very much like a nice description of the Truk Monarch (Monarcha rugensis (Hombron & Jacquinot)), and given the fact that most island-dwelling birds in Micronesia also occur on nearby atolls it is quite possible that there once was a native population of this bird here as well.

But we will probably never know for sure.

***

The most interesting things that I found out so far are.:

1: Micronesian bird names are odd (to my ears and eyes), I mean the Palau Ground Dove (Pampusana canifrons (Hartlaub & Finsch)) for example is named omekrengukl, I do not even know how to pronounce that. 🙂

2: Micronesia harbors only 148 native breeding bird species (including the extinct ones!).

3: The Micronesian landbirds do not only occur on the higher islands but also on the atolls, even on those atolls that are quite far away from the next high islands, a situation that is completely different from Polynesia, where the high islands almost entirely harbor a different avifauna than the atolls.

There may have been more species once, especially when we fill some of the illogical gaps between the islands and island groups.

*********************

References:

[1] Paul Hambruch: Nauru. Ergebnisse der Südsee-Expedition 1908-1910. II. Ethnographie: B. Mikronesien, Band 1.1 Halbband. Hamburg, Friedrichsen 1914

[2] Mac Marshall: The natural history of namoluk Atoll, eastern Caroline Islands. Atoll Research Bulletin 189: 1-53. 1975

[3] Donald W. Buden: The birds of Satawan Atoll and the Mortlock Islands, Chuuk, including the first record of Tree Martin Hirundo nigricans in Micronesia. Bulletin on the British Ornithologists’ Club 126(2): 137-152. 2006

[4] Dirk H. R. Spennemann: Extinctions and extirpations in Marshall Islands avifauna since European contact – a review of historic evidence. Micronesia 38(2): 253-266. 2006

*********************

edited: 04.01.2024

Have you ever heard of Lamotrek, Ngulu, or Woleai?

No?

Neither did I ….

These are the names of some of the atolls that form a squadron-like swarm around the Yap Islands – you have also never heard of the Yap Islands?

Well, let me help you out here, the Yap Islands are a part of the Federated States of Micronesia, which again are a part of Micronesia which is a name for the region of small islands that lie east of the Philippines, north of New Guinea, the Solomons and Vanuatu, and west of Polynesia.

***

I asked for the name Woleai especially because I only recently found out that the White-breasted Waterhen (Amaurornis phoenicurus (Pennant)) ‚recently‘ expanded its area of distribution from Southeast Asia to exactly this part of Micronesia. [1]

The photo below shows that species, the name of the photographer is just a coincidence, I swear. 🙂

I wrote ‚recently‘ in quotation marks because this bird apparently appeared here already in the 1970s, but no one took any notice of that until 2009, when some westerners cought one bird on the Woleai atoll.

This event is a very good exemplary for the whole state of the ornithological research in that region – we just do not know anything.

*********************

References:

[1] Donald W. Buden; Stanley Retogral: Range expansion of the White-breasted Waterhen (Amaurornis phoenicurus) into Micronesia. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 122(4): 784-788. 2010

*********************

*********************

edited: 01.06.2019

The genus Pareudiastes consists of two species that both are known from historical times, meaning ‘having been seen’ by western scientists. We can probably add at least two undescribed extinct forms that are known exclusively from scanty subfossil remains, one from Fiji and one from the Solomon Islands.

The two species of which at least skins remain are very little known, the puna’e (Pareudiastes pacificus Kubary, Hartlaub & Finsch) from Samoa is in fact the best known of them.

***

The puna’e, whose name roughly translates as “springs up“, is known to have inhabited the rainforests of Savai’i, Samoa; it is said by the natives to have lived in burrows, which were longer than a man’s arm and which ended in a sort of chamber in which the bird slept during the day.

The large eyes of the species indeed point to a somewhat nocturnal habit.

When the bird was disturbed it jumped up from its burrow with fluttering wings but being flightless it landed shortly after and run away quickly.

It is furthermore known that it was not a vegetarian species, since it died when it was fed with plant material but was “happy” when fed with insects.

***

There is at least one reliable account that indicates that this species also inhabited the neighboring island of ‘Upolu.:

“The Samoans always speak of the Pareudiastes as the ‘bird which burrows like a rat.’ Again and again when I have put the question to a native, ‘Do you know the Puna’ e?’ the reply has been, ‘No, I have never seen it; but that is the bird of which the old people speak that it used to be very plentiful long ago, and that it burrows like a rat and lives underground.’ It is very rarely that I have met with any one who has seen the bird; but I have met with two persons who have actually taken it in its burrow. The first is a man well known to me, and in whose veracity I have faith. He says that about four years ago [ca. 1870] he was one of a large party hunting feral pigs in the mountains of Upolu, when they came upon a burrow which one of the party pronounced to be the hole of a Puna’e. My informant says that he put his arm into the hole, and at its extremity (which he could barely reach) he found the bird. He drew it out, and, taking it home, tried to tame and feed it; but it would not eat, and soon died.” [1]

Yet, how is this possible? The islands of Savai’i and ‘Upolu are separated by the 13 km wide Apolima strait.

***

During the Pleistocene, the sea level was lower and Manono very likely was connected with ‘Upolu, but Apolima was not, and Savai’i and ‘Upolu also weren’t connected.

So, how did a flightless bird manage to get from one island to the other?

The answer might be that the Puna’e wasn’t flightless at the time when the sea level was lower, or that the birds from ‘Upolu represented a distinct (sub)species.

***

What do we know about the second historical known species, the Makira Woodhen (Pareudiastes silvestris (Mayr))?

This species is known from a single specimen that was taken in 1929 on the island of Makira, Solomon Islands in montane forest at an elevation of about 600 m, only its skin was preserved, the bones not, and it apparently was flightless or at least nearly so.

The natives called it kia and hunted it with dogs.

That’s all.

The species was apparently still ‘well-known’ by the natives in 1953, and they also said that it was not rare, nevertheless not a single one was ever seen since (by western scientists).

The Makira Woodhen, or Kia, however, is the sole member of this genus that may in fact still survive, and I personally hope that it might be rediscovered someday.

***

The two additional forms are, as I’ve said before, known only from some scanty subfossil remains found on the island of Buka in the northernmost part of the Solomon Islands as well as on Viti Levu, the largest of the Fijian Islands respectively.

***

The genus Pareudistaes should be merged with the genus Gallinula, by the way.

*********************

References:

[1] Letter from Rev. S. J. Whitmee. In: Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1874: 183-186

*********************

edited: 04.07.2023

Family incertae sedis

Chupkaornis keraorum Tanaka et al.

Judinornis nogotsavensis Nessov & Borkin

Pasquiaornis hardiei Todaryk, Cumbaa & Storer

Pasquiaornis tankei Todaryk, Cumbaa & Storer

Potamornis skutchi Elzanowski, Paul & Stidham

Baptornithidae

Baptornis advenus Marsh

Brodavidae

Brodavis americanus Martin et al.

Brodavis baileyi Martin et al.

Brodavis mongoliensis Martin et al.

Brodavis varneri (Martin & Cordes-Person)

Enaliornithidae

Enaliornis barretti Seeley

Enaliornis sedgwicki Seeley

Enaliornis seeleyi Galton & Martin

Hesperornithidae

Asiahesperornis bazhanovi Nesov & Prizemlin

Canadaga arctica Hou

Fumicollis hoffmani Bell & Chiappe

Hesperornis altus (Marsh)

Hesperornis bairdi Martin & Lim

Hesperornis chowi Martin & Lim

Hesperornis crassipes (Marsh)

Hesperornis gracilis Marsh

Hesperornis lumgairi Aotsuka & Sato

Hesperornis macdonaldi Martin & Lim

Hesperornis mengeli Martin & Lim

Hesperornis montana Schufeldt

Hesperornis regalis Marsh

Hesperornis rossicus Nesov & Yarkov

Parahesperornis bazhanovi Nessov & Prizemlin

*********************

edited: 30.06.2019

*********************

bearbeitet: 28.05.2019

Levaillant’s Sicrin de l’Imprimerie de Langlois, apparently meaning ‘Sicrin from the print of Langlois’ (?) is a strange bird drawn by Johann Friedrich Leberecht Reinhold that I discovered while flicking through the volumes of François Le Vaillant’s ‘Histoire naturelle des oiseaux d’Afrique’ from 1799.

Here it is.:

I must confess, first I had absolutely no idea what this astonishing bird is supposed to have been, it looks like some corvid bird, or a starling, possibly one of the strange starling species from the Philippine Islands, but what about the six porcupine spines in its face?

The bird is said to have been found at the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa, what I very much doubt it has, Monsieur Le Vaillant furthermore places it amongst the Jackdaws.

But let’s now just see what else Monsieur Le Vaillant has to tell us about this bird.:

„Le Sicrin est une espèce absolument nouvelle, et dont aucun naturaliste n’a fait mention encore; je fai placé parmi les choucas, parce que ce sont les oiseaux desquels je trouve qu’il se rapproche le plus, pour les formes de son bec, de ses pieds et de son corps. Au reste, si par la suite quelque voyageur nous apprend ses moeurs, que nous ignorons totalement, on lui donnera une autre place, si on juge qu’elle lui convienne mieux. Quant à moi, je le crois un vrai choucas, et cela pour l’avoir comparé attentivement avec tous les oiseaux de ce genre; je trouve même qu’il ressemble tellement au choquart ou choucas des Alpes, que si on lui retranchoit les six crins et la huppe qui le caractérisent si bien, on en feroit absolument le même oiseau; il est aussi de la même taille, mais il m’a paru un peu plus gros de la poitrine: il est vrai que, n’ayant vu cet oiseau qu’empaillé, il pourroit se faire qu’il ne dut sa rotondité quà une plus grande extension de la peau; cependant elle ne ma pas paru excessivement bourrée, puisque la peau n’étoit pas très-tendue. Le bec est absolument semblable aussi à celui du choquart, sinon qu’il est un peu plus pointu et plus épais à sa base. La queue est de même carrément coupée par le bout c’est-à-dire, que toutes ses pennes sont aussi longues les unes que les autres. Les aîles pliées s’étendent aux deux tiers de la longueur de la queue, qui a dix pennes.“ [2]

translation:

“The Sicrin is an absolutely new species, and of which no naturalist has yet reported; I did place them among the jackdaws, because they are the birds to which I find it comes closest, for the shapes of its beak, feet and body. For the rest, if afterwards some traveler informs us of more, which we are totally unaware of, we will give it another place, if we judge that it suits it better. As for me, I believe it to be a real jackdaw [M. Le Vaillant apparently was not that good in taxonomy ….], and that for having compared it attentively with all the birds of this kind; I even think that it resembles so much the cough or jackdaw of the Alps, that if we cut off the six horsehair [… actually real horse hair stucked into the bird?] and the crest that characterize it so well, we would make absolutely the same bird; it is also of the same size, but it seemed to me a little bigger of the breast: it is true that, having seen this bird only tempered [?], it could be done that it had its rotundity only to a greater extension of the skin; however it did not seem to me excessively drunk, since the skin was not very tense. The bill is absolutely similar to that of the cough, except that it is a little more pointed and thicker at its base. The tail is likewise cut off by the end, that is to say, that all its feathers are of equal length. The folded wings extend to two-thirds of the length of the tail, which has ten feathers.”

and

„Cet oiseau est remarquable par les crins ou longues plumes sans barbes qui ornent les côtés de sa tête, (à peu près comme dans l’espèce d’oiseaux de paradis que Buffon a nommée le sifilet), et par une belle huppe flottante qui, se couchant en arrière, ombragela tête. Les pieds sont conformés comme ceux du choquart; le bec est d’un jaune de citron, et prend une teinte d’orange sur son arête supérieure et vers les narines; celles-ci sont couvertes de poils ou plumes déliées, qui se dirigent en avant comme chez tous les oiseaux du genre des corbeaux. Les pieds et les ongles sont noirs.“ [2]

translation:

„This bird is remarkable for the hair or long feathers without barbs, which decorate the sides of its head (almost as in the species of bird of paradise that Buffon named the Sifilet [Western Parotia (Parotia sefilata (J. R. Forster))], and by a beautiful floating crest which, lying backward, shades its head. The feet are shaped like those of the cough; the beak is lemon yellow, and has an orange hue on its upper ridge and towards the nostrils; these are covered with loose hairs and feathers, which go forward as in all the birds of the crow kind. The feet and nails are black.“

and

„Il est plus que probable que ces oiseaux ont la faculté de redresser ces filets, et par conséquent de les resserrer contre le corps dans l’action du vol, dont ils gêneroient les mouvemens s’ils balotoient au gré des vents: je présume du moins cette faculté, d’après la longueur du tuyau qui s’implantoit dans la peau, et qui étoit trop grand pour ne pas faire soupçonner qu’il devoit pénétrer dans un muscle extenseur, propre à le faire mouvoir au gré de l’oiseau: ce qui me le donnoit encore à penser, c’est que dans la partie de la joue où ils entroient, toute la peau étoit plus épaisse et plus dure que par-tout ailleurs, et qu’on y remarquent très-distinctement une cavité profonde oùse logeoit le tuyau du filet que j’avois arraché, comme on le voit sur la métacarpe et le croupion de tous les oiseaux, quand on leur détache une penne soit de l’aîle ou de la queue. Je ne hasarderai point de désigner l’usage dont ces barbes peuvent être à cet oiseau, ni quel but s’est proposé la nature dans cette singulière production, que je regarde, au reste, comme un simple ornement. Combien de fois nos philosophes ne se sontils pas trompés et n’ont-ils pas égaré les autres hommes, lorsqu’ils ont voulu donner raison des causes que la nature avoit sans doute destinées à rester cachées aux foibles humains, d’un côté trop au-dessous de sa puissance pour les concevoir, et d’un autre trop audacieux peut-être pour être initiés, sans danger, dans ses mystères! O nature! il y a longtems, hélas! que les aveugles mortels auroient détruit ton ouvrage, et troublé cette belle harmonie de l’univers s’ils avoient pu te suivre dans ta marche et te deviner un seul instant!“ [2]

translation:

„It is more than probable hat these birds have the faculty of straightening these filaments, and consequently of tightening them against the body in the action of the flight, of which they disturb the movements if they struggle with the winds: I presume at least this faculty, according to the length of the pipe which was implanted in the skin, and which was too large not to make us suspect it had to penetrade into an extensor muscle, capable of causing it to move at the whim of the bird: what gave me still to think is, that in the part of the cheek they entered, the whole skin was thicker and more lasting than anywhere else, and we remark very distingly a deep cavitiy where the tube of the net which I had thorn off, as one sees on the metacarpus and the rump of all the birds, when one detaches a quill either of the ellbow or the tail. I will not venture to designate the use of which these beards can to be to this bird, nor what goal has nature proposed itself in this singular production, which I regard, moreover, as a simple ornament. How many times have our philosophers become unaccustomed to themselves, and have they not treated other men when they wished to give reason to the causes which nature had doubtless intended to remain hidden from the eak human beings, on the one hand too much below its power to to conceive them, and another too audacious perhaps to be initiated, without danger, into his mysteries! O nature! Long ago alas! That the blind mortals would have destroyed your work, and disturbed this beautiful harmony of the universe if they could have followed you in your march and guess you one moment!“ [what the ***, was he drunk here?]

By the way I could not find out what ‚Sicrin‘ is supposed to mean.

For about one day I was quite sure that this bird is nothing but a made-up piece, probably a Parotia species, for example the Western Parotia (Parotia sefilata (J. R. Forster)), with the glossy breast-shield feathers and the spatulate vanes of the six ornamental feathers below the eyes having been removed – even before translating and reading all the stuff above.

Well, well, but reading the original ‚description‘ including another, much older depiction, I am quite convinced that this mysterious bird is something completely different ….

a section of the original ‘description’:

“Il est à peu près de la grosseur du précédent. Sa longueur depuis le bout du bec jusqu’à celui de la queue est d’onze pouces quatre lignes, & jusqu’à celui des ongles de huit pouces dix lignes. Son bec depuis sa pointe jusqu’aux coins de la bouche a un pouce six lignes de long; sa queue cinq pouces; son pied douze lignes; & celui du milieu des trois doigts antérieurs, joint avec l’ongle, douze lignes & demie: les latéraux sont un peu plus courts; & celui de derriere est presque aussi long que celui du milieu de ceux de devant. Il a un pied sept pouces trois lignes de vol, & ses aíles, lorsqu’elles sont pliées, s’étendent jusqu’à la moitié de la longueur de la queue. La tête, la gorge & le col sont couverts de plumes d’un noir-verd très – brillant, celles de la partie supérieure du col font très – étroites & beaucoup plus longues que les autres. Elles glissent sur le dos sélon les différens mouvemens de la tête & du col. Les plumes qui retombent sur les narines sont d’un noir de velour. Audessus de ces plumes partent de l’origine du demi-bec supérieur quelques poils noirs, longs de trois pouces & très-fléxibles: & au-dessous tout le long de la bâse du bec, jusque vers les coins de la bouche, sont d’autres poils noirs, beaucoup plus courts & roides comme des soyes. Le dos, le croupion, la poitrine, le ventre, les côtés, les jambes & les couvertures du dessus & du dessous de la queue sont d’un noir de velours changeant en verd brillant. Celles du dessus & du dessous des aîles sont d’un noir-verd éclatant & changeant en violet. Les plumes des aíles sont de la même couleur endessus du côté extérieur feulement, & noires du côté intérieur; & en-dessous elles sont noirâtres. La première des plumes de l’aíle est plus courte de deux pouces sept lignes que la quatrième & la cinquième, qui sont les plus longues de toutes. Les plumes de la queue, qui sont toutes d’égale longueur, sont d’un noir-verd en-dessus & tout-à-fait noirâtres en-dessous. Le bec, les pieds & les ongles sont noirs. On le trouve au Cap de Bonne Esperance, d’où il a été apporté à M. l’Abbé Aubry, qui le conserve dans son cabinet.“

translation:

“He is about the size of the preceding. Its length from the tip of the beak to that of the tail is eleven inches four lines, & up to that of the nails eight inches ten lines. Its beak from its point to the corners of the mouth is one inch six lines long; his tail five inches; his foot twelve lines; & that of the middle of the three anterior toes, joined with the nail, twelve lines & a half: the lateral ones are a little shorter; & the one behind is almost as long as the one in the middle of the front ones. He has one foot seven inches three flight lines, & his wings, when folded, extend to half the length of the tail. The head, the throat, & the neck are covered with feathers of very brilliant black-green, those of the upper part of the neck are very narrow & much longer than the others. They slide on their backs, according to the different motions of the head & the collar. The feathers that fall on the nostrils are of a black velvet.Above these feathers, from the origin of the upper half-beak, are a few black hairs, three inches long & very flexible; & below all the length of the bill-body, as far as the corners of the mouth, are other black hairs, much shorter & stiff like sores. The back, rump, chest, belly, sides, legs & covers of the top & bottom of the tail are velvet black, shiny green. Those on the top and bottom of the elbows are of a shiny black-green & changing into violet. The feathers of the birds are of the same color, on the outer side, & black on the inner side; & below, they are blackish. The first of the feathers of the ale is shorter by two inches seven lines than the fourth & the fifth, which are the longest of all. The feathers of the tail, which are all of equal length, are of a black-green above & quite blackish below. The beak, the feet & the nails are black. It is found at the Cape of Good Hope from where it was brought to the Abbé Aubry, who keeps it in his cabinet.” [1]

… a Hair-crested Drongo (Dicrurus hottentottus ssp. hottentottus (L.)) originally described in 1766, also as being from the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa, by the way.

This bird actually comes from Southeast Asia, where it has a quite wide distribution, doesn’t it fit well with the description? 🙂

*********************

[1] Mathurin-Jacques Brisson: Ornithologie, ou, Méthode contenant la division des oiseaux en ordres, sections, genres, especes & leurs variétés: a laquelle on a joint une description exacte de chaque espece, avec les citations des auteurs qui en ont traité, les noms quils leur ont donnés, ceux que leur ont donnés les différentes nations, & les noms vulgaires. Vol 2. Parisiis: Ad Ripam Augustinorum, Apud Cl. Joannem-Baptistam Bauche, Bibliopolam, ad Insigne S. Genovesae, & S. Joannis in Deserto 1760

[2] François Le Vaillant: Histoire naturelle des oiseaux d’Afrique. A Paris: Chez J. J. Fuchs, Libraire, Rue des Mathurins, Hótel de Cluny. Vol. 2. 1799

*********************

edited: 15.05.2019

Alcmona-‘Vogel’ (Alcmonavis poeschli Rauhut, Tischlinger & Foth)

Diese Art, die gerade erst beschrieben wurde, ist nur anhand von Teilen der Flügel, bzw. eines Flügels, bekannt (siehe Foto).

***

Der ‘neue Vogel’ lebte in was vor 150 Millionen Jahren der so genannte Solnhofen-Archipel war, Seite an Seite mit den berühmten Archaeopterygidae, war aber offenbar nicht sehr nah mit diesen verwandt.

Die wenigen Knochen sind, zumindest für meine Augen, äußerlich denen von Archaeopteryx albersdoerferi Kundrát et al. und Wellnhoferia grandis Elżanowski oder vielleicht sogar Jeholornis prima Zhou & Zhang aus China ziemlich ähnlich; sie zeigen aber immerhin, dass dieses Tier besser ans Fliegen angepasst war als die zeitgleich existierenden ‘Urvögel’, darüber hinaus wird er aber, zumindest äußerlich, recht ähnlich ausgesehen haben.

***

Bis jetzt wurden nur die Überreste eines einzigen Arms, bzw. Flügels gefunden – ich hoffe es werden weitere Funde folgen.

*********************

Quelle:

[1] Oliver W. M. Rauhut; Helmut Tischlinger; Christian Foth: A non-archaeopterygid avialan theropod from the Late Jurassic of southern Germany eLife DOI: 10.7554/eLife.43789.001. 2019

*********************

bearbeitet: 15.05.2019

During the last few days the online newspapers were trying to outdo each other with silly headlines, headlines like … :

“The bird that came back from the dead” or: “Extinct species of bird came back from the dead, scientists find” or, the worst of them all: “Scientists discover bird that came back from the dead – A species which became extinct 136,000 years ago in a rare flood on an Indian Ocean atoll has now re-emerged in the same place“

***

What is wrong with that?

Well, a lot, but let’s just start with the statement that their isn’t any species that really goes extinct and then comes back, also not a rail species!

We actually deal with two distinct species here, or let’s rather say, with two distinct taxa, since they may not be species but subspecies.

***

May I introduce the White-throated Rail (Dryolimnas cuvieri (Pucheran)), a very beautiful rail species that is endemic to the island of Madagascar and that apparently has also colonized the island of Mayotte northeast of Madagascar.

This species obviously is the source of several other flightless species and subspecies that are known to have existed on many of the islands around Madagascar, such forms are known from the islands of Mauritius and Réunion west of Madagascar and others from some of the atolls that belong to the Seychelles north of Madagascar, including the Aldabra atoll.

And the Aldabra atoll in fact is the only place where such a flightless form (subspecies or species if you want) still survives until today, this is the Aldabra Rail (Dryolimnas (cuvieri ssp.) aldabranus (Günther)).

***

Long time ago, some White-throated Rails for which reason ever, took a flight to the atoll to find it uninhabited (by rails) and decided to stay there … over time the rails that were born on this predator-free island stopped using their wings and their descendants again finally became completely flightless.

But then the Aldabra atoll just disappeared due to total inundation in the middle Pleistocene, about 340000 years before present, leading to the extinction of all endemic animals and plants, including this ‘First’ Aldabra Rails.

***

Then again, around 100000 years before present, the sea-level begun to sink and the Aldabra atoll reemerged.

Again, some White-throated Rails left their home island of Madagascar and took a flight to the north to find a new home on the now rail-free Aldabra atoll, and the story took the same direction as thousands of years before, and the final result are the recent endemic, flightless Aldabra Rails that one can see when visiting the atoll.

***

So, the Aldabra atoll was inhabited by two distinct lineages of flightless rails at two different times in history, respectively prehistory, that, despite both descenting from one and the same ancestor species, still represent two completely distinct forms, whether they are referred to as subspecies or as species.

*********************

References:

[1] Julian P. Hume; David Martill: Repeated evolution of flightlessness in dryolimnas rails (Aves: Rallidae) after extinction and recolonization on Aldabra. Zoolocigal Journal of the linnean Society 20: 1-7. 2019

*********************

edited: 10.05.2019

Cratoavis cearensis, an enantiornithiform bird from the lower Cretaceous of the extremely interesting Crato Formation in Brazil.

This bird is known from a single specimen that apparently was not fully grown, it was altogether only about 12 cm long (including the tail streamers)!

Yet, I have no idea how large it may have got when fully adult, who knows.

***

The Crato Formation is otherwise known for its numerous plant fossils, many of them angiosperms, so I cannot really decide yet which plant species may fit with this bird, but time will show ….

*********************

edited: 02.04.2019

Agnopteridae

Agnopterus hantoniensis Lydekker

Agnopterus laurillardi Milne-Edwards

Agnopterus turgaiensis Turgarinov

Palaelodidae

Adelalopus hoogbutseliensis Mayr & Smith

Megapaloelodus connectens Miller

Megapaloelodus goliath Milne-Edwards

Megapaloelodus opsigonus Brodkorb

Megapaloelodus peiranoi Agnolin

Palaelodus ambiguus Milne-Edwards

Palaelodus aotearoa Worthy et al.

Palaelodus crassipes Milne-Edwards

Palaelodus germanicus (Lambrecht)

Palaelodus gracilipes Milne-Edwards

Palaelodus kurochkini Zelenkov

Palaelodus minutus Milne-Edwards

Palaelodus pledgei Baird & Vickers-Rich

Palaelodus steinheimensis Fraas

Palaelodus wilsoni Baird & Vickers-Rich

Phoenicopteridae

Elornis anglicus Aymard

Elornis grandis Milne-Edwards

Elornis littoralis Milne-Edwards

Harrisonavis croizeti (Gervais)

Juncitarsus gracillimus Olson & Feduccia

Juncitarsus merkeli Peters

Leakeyornis aethiopicus (Harrison & Walker)

Phoeniconaias gracilis Miller

Phoeniconotius eyrensis Miller

Phoenicopterus copei Shufeldt

Phoenicopterus floridanus Brodkorb

Phoenicopterus minutus Howard

Phoenicopterus novaehollandiae Miller

Phoenicopterus siamensis Cheneval

Phoenicopterus stocki (Miller)

*********************

edited: 01.04.2019

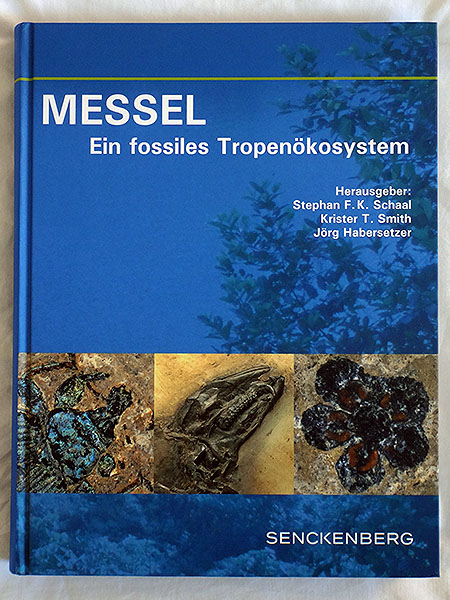

Stephan F. K. Schaal; Krister T. Smith; Jörg Habersetzer: Messel – Ein fossiles Tropenökosystem. E. Schweizerbart’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung 2018

*********************

This is the latest summary of the current knowledge of the fossil fauna and flora of the Middle Eocene of Messel, Germany. You can actually get it in two versions, a German one and a English one.

The book indeed covers all of the mammal-, bird-, reptile-, amphibian-, and fish species, as well as probably only some of the insect species known at the date of publication, yet, and that is very annoying, contains only a very small ammount of plant species, which probably is because their fossils are not yet fully examined, who knows.

There are photos of all species covered, reconstructions of some of the mammals, but actually none of the birds, however, the book contains three murals (at least I think they are murals), which again show several of the Messel birds (however, without naming them), among them the famous Messel ‘rail’, unfortunately with a way too short tail and a fleshy comb on its head (I will get back to that some time ….).

All in all, the book can be recommended to all who are interested in Eocene biodiversity! 🙂

*********************

edited: 20.03.2019

I have some free days right now, actually I have five days holiday right now!

So I decided to draw a bit … which, of course, hasn’t been that much successful so far … however, here are two pieces that I have at least already sketched, two members of one of the most colorful bird families at all, the tanagers (Thraupidae).

*********************

edited: 20.03.2019

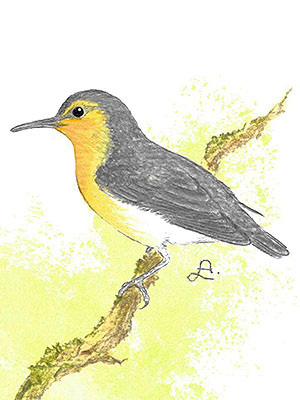

This species has only just been described – Creme-eyed Bulbul (Pycnonotus pseudosimplex Shakya et al.); it is one of the many cryptic species that have been previously overlooked.

The species appears to be more closely related to the Gray-fronted Bulbul (Pycnonotus cinereifrons(Tweeddale)) from the island of Palawan, Philippines than to the White-eyed Bulbul (Pycnonotus simplexLesson) with which it shares its habitat on the Indonesian island of Borneo and which it closely resembles. [1]

*********************

*********************

References:

[1] Subir B. Shakya, Haw Chuan Lim, Robert G. Moyle, Mustafa Abdul Rahman, Maklarin Lakim, Frederick H. Sheldon: A cryptic new species of bulbul from Borneo. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club 139(1): 46-55. 2019

*********************

bearbeitet: 20.07.2023

Lithornithidae

Calciavis grandei Nesbitt

Fissuravis weigelti Mayr

Lithornis celetius Houde

Lithornis hookeri (Harrison)

Lithornis nasi (Harrison)

Lithornis plebius Houde

Lithornis promiscuous Houde

Lithornis vulturinus Owen

Paracathartes howardae Harrison

Pseudocrypturus cercanaxius Houde

*********************

edited: 18.03.2019

Opisthodactylidae

Diogenornis fragilis de Alvarenga (?)

Opisthodactylus horacioperezi Agnolin & Chafrat

Opisthodactylus kirchneri Noriega et al.

Opisthodactylus patagonicus Ameghino

Rheidae

Heterorhea dabbeni Rovereto

Hinasuri nehuensis Tambussi

Rhea anchorenense (Ameghino & Rusconi)

Rhea fossilis Moreno & Mercerat

Rhea mesopotamica (Agnolín & Noriega)

Rhea subpampeana Moreno & Mercerat

*********************

edited: 16.03.2019

Ciconiidae

Ciconia gaudryi Lambrecht

Ciconia kahli Haarhoff

Ciconia louisebolesae Boles

Ciconia lucida Kurochkin

Ciconia maltha Miller

Ciconia minor Harrison

Ciconia nana (De Vis)

Ciconia sarmatica Grigorescu & Kessler

Ciconia sp. ‘Las Breas de San Felipe, Kuba’

Ciconia sp. 1 ‘Lee Creek Mine, USA’

Ciconia sp. 2 ‘Lee Creek Mine, USA’

Ciconia stehlini Jánossy

Eociconia sangequanensis Hou (?)

Leptoptilus arvernensis Milne-Edwards

Leptoptilos falconeri Milne-Edwards

Leptoptilos indicus (Harrison)

Leptoptilos lüi Zhang et al.

Leptoptilos patagonicus Noriega & Cladera

Leptoptilos pliocenicus Zubareva

Leptoptilos richae Harrison

Leptoptilos robustus Meijer & Awe Due

Leptoptilos siwalicensis Harrison

Leptoptilos sp. ‘Baringo District, Kenia’

Leptoptilos titan Wetmore

Mycteria milleri (Short)

Mycteria wetmorei Howard

Palaeoephippiorhynchus dietrichi Lambrecht

Palaeoephippiorhynchus edwardsi (Lydekker) [1]

Palaeopelargus nobilis De Vis

Pelargodes magna Milne-Edwards

Pelargopsis stehlini Gaillard

Pelargopsis trouessarti Gaillard

Pseudotantalus milneedwardsii Shufeldt

Tantalus breselensis Marmora

Xenorhynchopsis minor De Vis

Xenorhynchopsis tibialis De Vis

Xenerodiopidae (?)

Xenerodiops mycter Rasmussen

*********************

Quelle:

[1] Jiří Mlíkovský: Early Miocene birds of Djebel Zelten, Libya. Časopis Národního muzea, Řada přírodovědná 172(1-4): 14-120. 2003

*********************

bearbeitet: 24.04.2024

Familie incertae sedis

Eocuculus cherpinae Chandler

Cuculidae

Centropus antiquus Gervais

Centropus colossus Baird

Chambicuculus pusillus Mourer-Chauvire, Tabuce, Essid, Marivaux, Khayati, Vianey-Liaud & Ben Haj Ali

Cuculus csarnotanus Jánossy

Cuculus pannonicus Kessler

Cursoricoccyx geraldinae Martin & Megel

Geococcyx californianus ssp. conklingi Howard [1]

Neococcyx mccorquodalei Weigel

Thomasococcyx philohippus Steadman

*********************

Quellen:

[1] David W. Steadman; Joaquin Arroyo-Cabrales; Eileen Johnson; A. Fabiola Guzman: New information on the Late Pleistocene San Josecito Cave, Nuevo León, Mexico. The condor 96: 577-589. 1994

*********************

bearbeitet: 10.03.2019

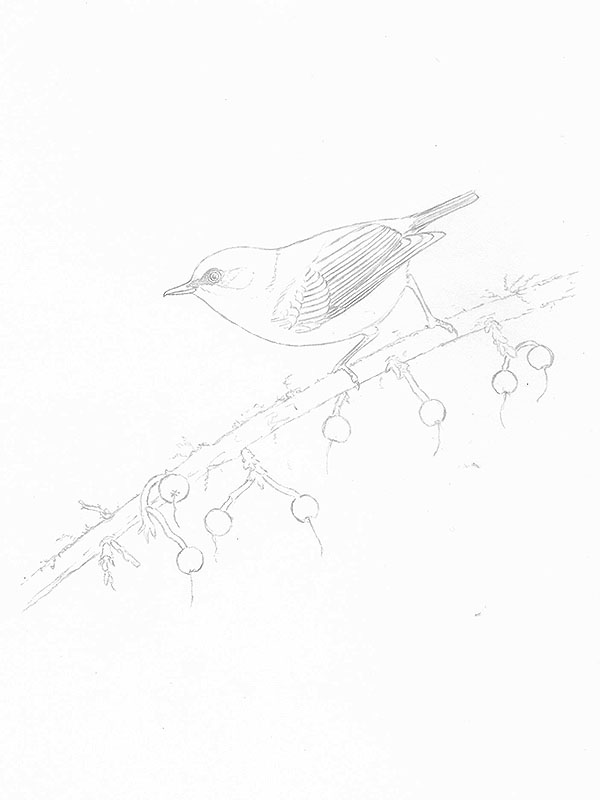

Here we have the two species of finch-like passeriform birds that had been described at the beginning of this year, Eofringillirostrum boudreauxi and Eofringillirostrum parvulum, both from the Eocene, the first from North America, the second, smaller species from Europe.

***

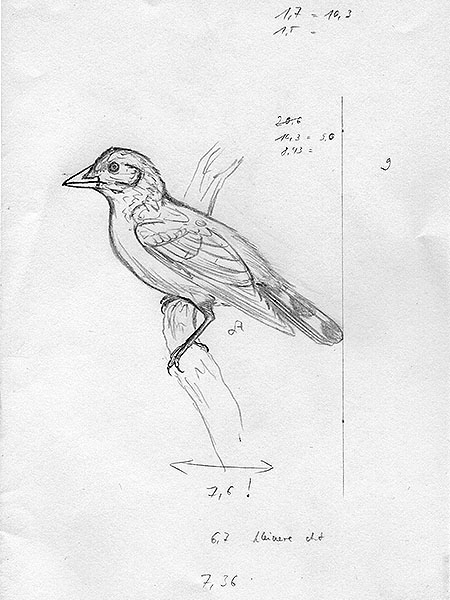

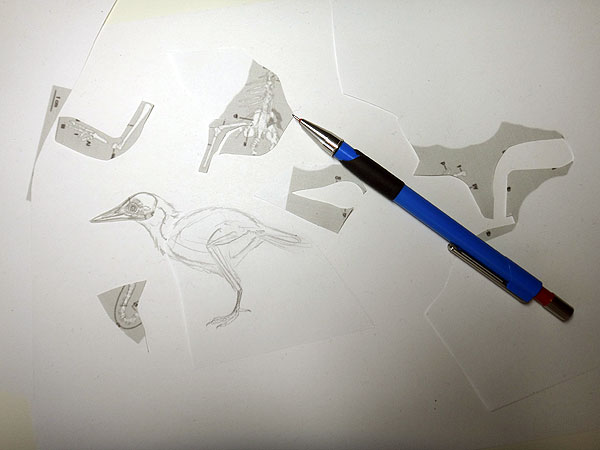

Eofringillirostrum boudreauxi Mayr, Ksepka & Grande

This is the larger of the two known species, reaching about 10 cm in length, it also is the older one, having lived in the Early Eocene about 52 Million years ago in what today is Wyoming, USA.

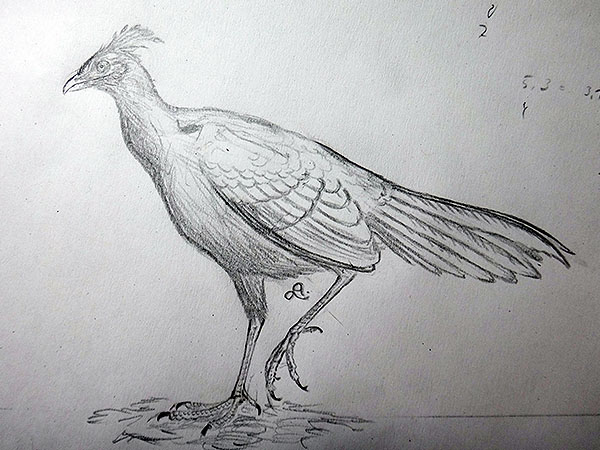

This is what I call a pre-sketch, or a working sketch, it’s just the very first step in reconstructing a fossil bird, in which this particular species is drawn in a simple side-view, usually smaller than life-size.

Eofringillirostrum parvulum Mayr, Ksepka & Grande

This bird may have reached a length of only about 9 cm, it lived in the Middle Eocene of what today is the State of Hesse in Germany.

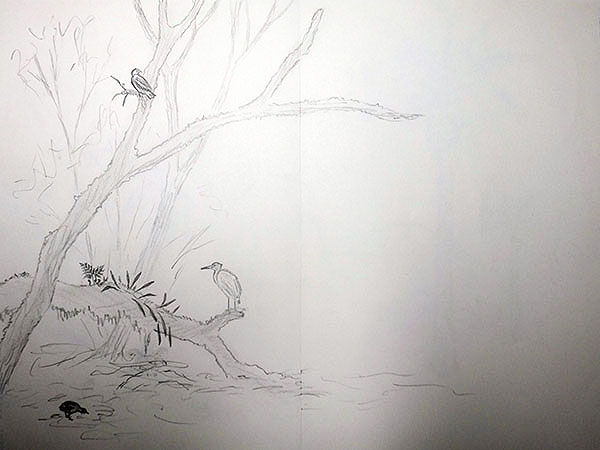

I sketched it together with a reconstructed infructescence of Volkeria messelensis Smith, Collinson et al., a plant from the family Cyperaceae that was growing around the Messel lake, and whose seeds may indeed have been eaten by this presumably seed-eating bird.

*********************

edited: 05-03.2019

Family incertae sedis

Botauroides parvus Shufeldt

Eocolius walkeri Dyke & Waterhouse

Palaeospiza bella Allen

Chascacocoliidae

Chascacocolius cacicirostris Mayr

Chascacocolius oscitans Houde & Olson

Selmeidae

Selmes absurdipes Peters

Sandcoleidae

Anneavis anneae Houde & Olson

Eobucco brodkorbi Feduccia & Martin

Eoglaucidium pallas Fischer

Eoglaucidium sp. ‘Messel, Germany’

Sandcoleidae gen. & sp. ‘Messel, Germany’

Sandcoleus copiosus Houde & Olson

Tsidiiyazhi abini Ksepka et al.

Uintornis lucaris Brodkorb

Uintornis marionae Feduccia & Martin

Coliidae

Celericolius acriala Ksepka & Clarke

Coliidae gen. & sp. ‘Hoogbutsel, Belgium’

Coliidae gen. & sp. ‘Moncucco Torinese, Italy’

Coliidae gen. & sp. ‘Grillental, Namibia’

Colius hendeyi Vickers-Rich & Haarhoff

Colius palustris (Milne-Edwards)

Limnatornis archiaci Milne-Edwards

Limnatornis consobrinus Milne-Edwards

Limnatornis paludicola Milne-Edwards

Masillacolius brevidactylus Mayr & Peters

Oligocolius brevitarsus Mayr

Oligocolius psittacocephalon Mayr

Primocolius minor Mourer-Chauviré

Primocolius sigei Mourer-Chauviré

*********************

edited: 05.03.2019