*********************

bearbeitet: 31.03.2021

*********************

bearbeitet: 31.03.2021

*********************

bearbeitet: 31.03.2021

*********************

bearbeitet: 31.03.2021

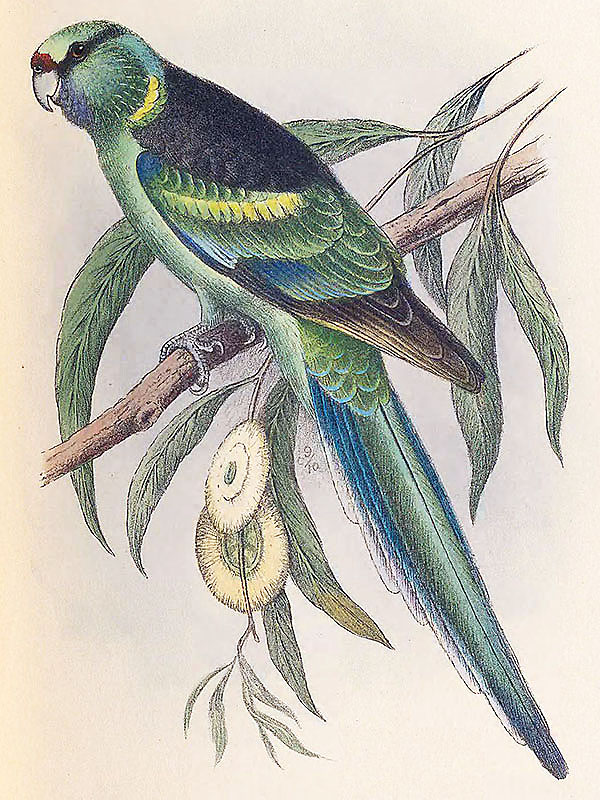

Lady Tavistocks Sittich (Barnardius crommelinae Mathews)

Diese eigentlich vollkommen unbekannte ‘Art’ ist nur anhand eines einzigen Exemplars bekannt, eines Weibchens, das offenbar eine Zeitlang im Aviarium des Marquis of Tavistock in Gefangenschaft gehalten und nach dessen Frau benannt wurde. [1]

Es handelt sich hierbei offenbar um einen Barnardsittich (Barnardius barnardi (Vigors & Horsfield)) dem große Teile der gelben Areale fehlen. [2]

*********************

*********************

Quelle:

[1] Gregory M. Mathews: A new form of Barnardius. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club 46(299): 21. 1925

[2] Julian P. Hume: Extinct Birds. Bloomsbury Natural History; 2nd edition 2017

*********************

bearbeitet: 27.03.2021

Obskurer Papagei (Psittacus obscurus)

Der so genannte Obskure Papagei, der eigentlich besser Dunkler Papagei heißen sollte wurde ursprünglich im Jahr 1757 durch Fredric Hasselquist bzw. Carl von Linné beschrieben, dies ist die Beschreibung.:

“PSITTACUS (obscurus) niger, vertise cinereonigrescente vario, cauda cinerea.

CAPUT oblongum, lateribus compressum, dorso depressum, respectu corporis satis magnum.

Rostrum totum latum, crassum, obtusissimum, aduncum, capite triplo brevius. Maxilla superior subconvexa, inferius latiuscula, dorsum versus magis contracta, mobilis. Ad basin maxillae superioris infra nares sulcus conspieitur, quasi imbricata esset pergit. Apex maxillae superioris aduncus extra maxillam inferiorem, quo ad quartam sui partem extensus, extremitate obtusiusculus. Lobulus utrinque ad basin apicis, maxillae inferiori dum clauditur os, supra impositum, Maxilla inferior superiore crassior, magis comnvexa, brevior, quantitate apicis superioris, basi subtus gula distans, posterius aequalis; apice obtusa & fere emarginata; sinus semicircularis ad basin apicis. Nares proxime supra rostrum, perfecte circulares, magnitudine pennae gallinaceae.

Oculi vertici quam gulae, naribus etiam quam basi capitis propiores. Iris flava. Pupilla nigra. Area oculorum usque a fine maxillae superioris ad initium verticis latitudine, & a naribus, fere usque ad basin verticis longitudine nuda, rugosa, pilis vix conspicuis obsita.

Aurium apertura oblonga, transversalis, ab oculis aequali spatio, ut oculi a naribus, distans, basi capitis quam vertici multo propior, plumis tenuibus & membrana retractilis tecta.

Remiges circiter 20:1, 2 reliquis longiores; 3, 4, 5, paulo breviores, aequales; 6. 7. 8 ordine decrescentes; reliqui aequales breviores.

CAUDA cuneiformis. Rectrices circiter 10, laterales breviore intermedii longioribus.

PEDES, crura plumosa, usque ad flexuram tarsi.

Digiti 4: antici 2 & postici 2; ex anterioribus internus exteriori tribus articulis brevior est posterioribus, interior exteriori dimidio brevior; omnes digiti squamosi, squamis imbricatis, articulis duobus insimis impositis; reliqua pars pedis tuberculata, tuberculis levibus, circularibus, parum elevatis.

Lingua crassa, apice obtusissima & fere semicirculari, lateribus marginata, marginibus fursum inflexis, unde canaliculata evadit.

Ungues adungi, obtusiusculi.

COLOR: Rostrum nigrum. Area oculorum alba. Vertex ex cinereo & nigrescente variegatus. Colum & Alae supra nigra.

Abdomen & crura cinerea, cum lineis transversalibus canis. Tubercula pedum nigra. Ungues nigri. Cauda tota cinerea.

MAGNITUDO Graculi.” [1]

***

Ich muss gestehen, dass ich meine Übersetzungsversuche hier aufgegeben habe da sie nirgendwohin führten.

Wie dem auch sei, John Latham, der bekannte Autor vieler Vogelbücher des späten 18./frühen 19. Jahrhunderts, führt die Art im 2. Teil seines Werkes “A general history of birds”.:

“SIZE of a Jay. Bill black, the feathers round the base of it black, rough, and beset with hairs; space round the eye white; irides yellow; crown variegated cinereous and black; upper parts of the neck and wings black; belly and thighs cinereous, marked with transverse hoary lines; tail wholly ash-coloured, cuneiform; legs tuberculated, black; toes the same; claws crooked, and black.

Inhabits Africa. The only one who has described this is Hasselquist, from whom Linnaeus had his account; as to that which the latter refers in Brisson, it is quite a different species, and he mentions it as such in his last Mantissa.” [2]

Übersetzung:

“GRÖßE eines Hähers. Schnabel schwarz, die Federn rund um die Basis schwarz, rau und mit Haaren besetzt; Bereich um das Auge weiß; Iriden gelb; Scheitel grau und schwarz variegiert; obere Teile des Halses und Flügel schwarz; Bauch und Oberschenkel grau, markiert mit quer verlaufenden grauen Linien; Schwanz ganz aschfarben, keilförmig; Beine höckerig, schwarz; Zehen gleich; Krallen krumm und schwarz.

Bewohnt Afrika. Der Einzige, der ihn beschrieben hat, ist Hasselquist, von dem Linnaeus seinen Bericht hatte; worauf sich letzterer in Brisson bezieht, so handelt es sich um eine ganz andere Art, und er erwähnt sie in seiner letzten Mantisse als solche.“

***

Der Vogel wird Psittacus genannt und mag mit dem Graupapagei (Psittacus erithacus L.) und dem Timneh-Papagei (Psittacus timneh Fraser) verwandt gewesen sein; aber halt! Nahezu sämtliche Papageien wurden ursprünglich als Psittacus beschrieben, so dass dieser Name ebenfalls nirgendwo hinführt, es ist nicht einmal sicher, dass es sich hier überhaupt um einen Papagei handelt.

*********************

*********************

Quellen:

[1] Fredric Hasselquists: Iter Palæstinum, eller Resa til Heliga Landet, förrättad ifrån år 1749 til 1752, med beskrifningar, rön, anmärkningar, öfver de märkvärdigaste naturalier, på Hennes Kongl. Maj:ts befallning, utgiven af Carl Linnaeus. Stockholm: Trykt på L. Salvii kåstnad 1757

[2] John Latham: A general history of birds. Winchester: printed by Jacob and Johnson, for the author: — sold in London by G. and W. B. Whittaker, Ave-Maria-Lane; John Warren, Bond Street, W. Wood, 428, Strand; and J. Mawman, 39, Ludgate-Street 1821-1828

[3] Julian P. Hume: Extinct Birds. Bloomsbury Natural History; 2nd edition 2017

*********************

edited: 26.03.2021

Purpurnaschvogel (Chlorophanes purpurascens Sclater & Salvin)

Diese ‘Art’ wurde im Jahr 1873 beschrieben, es ist nur ein einziges Exemplar bekannt, welches offenbar irgendwo in Venezuela gefunden wurde; einer anderen Quelle zufolge in Trinidad. [1][2]

Es handelt sich hierbei tatsächlich um einen Hybriden mit dem Kappennaschvogel (Chlorophanes spiza (L.)) und dem Türkisnaschvogel (Cyanerpes cyaneus (L.)) als Elternarten. [2]

*********************

*********************

bearbeitet: 25.03.2021

*********************

Quellen:

[1] Philip Lutley Sclater: Catalogue of the Passeriformes, or perching birds, in the collection of the British Museum. Fringilliformes: part II; containing the families Coerebidae, Tanagridae, and Icteridae. London 1886

[2] Julian P. Hume: Extinct Birds. Bloomsbury Natural History; 2nd edition 2017

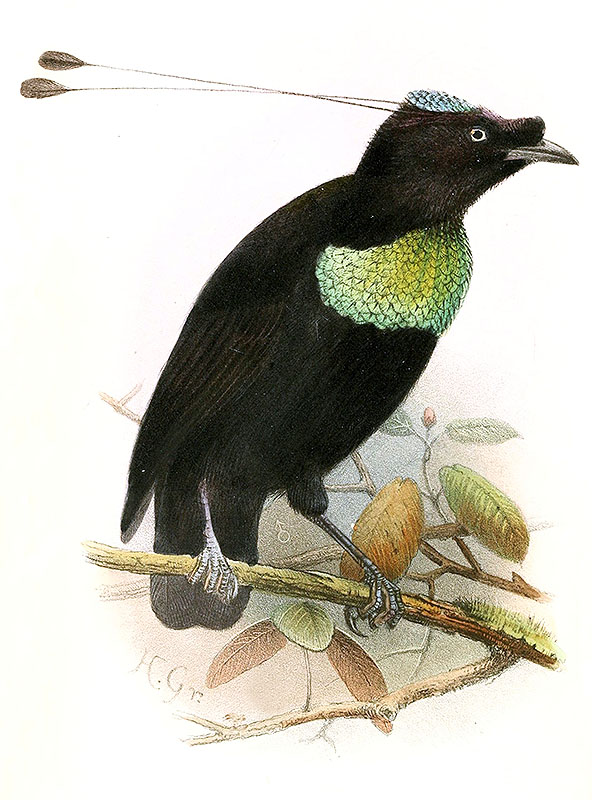

Mähnenparadiesvogel (kein wissenschaftlicher Name)

“LENGTH ten inches. Bill one inch and a quarter long, a trifle bent, and dusky, the base surrounded with velvet-like black feathers, covering the nostrils; top of the head, even with the eye, and to the beginning of the back, deep green, varying to bright green in some lights; the feathers of a plush-like texture; those on the hind part of the neck are long, pointed, and like hackles, but on the chin and throat they are similar to those on the crown, and both appear, in some lights, to be scaly, either indigo or green, and glossy, like metal; on each side of the neck is a stripe of blue, dividing the green above and below, and coming forwards to the breast, where it occupies a broad space; on the middle of the crown arise four bristles, near two inches long, tending backwards; upper part of the back, and wings, greenish black, in some lights appearing quite black; from the breast to the vent deep, dull ash-colour; tail even at the end, and three inches in length, the two middle feathers dull green, pointed at the tips; the others dusky within, and green on the outer webs, and all of them curve a little outwards; legs scaly; claws black, and hooked, though not very stout.

Native place uncertain; in the collection of General Davies.” [1]

Übersetzung:

“LÄNGE zehn Zoll [ca. 25,5 cm]. Schnabel einen Zoll und ein Viertel lang, eine Kleinigkeit gebogen und düster, die Basis von samtartigen schwarzen Federn umgeben, die die Nasenlöcher bedecken; Oberseite des Kopfes, in Augenhöhe, und bis zum Anfang des Rückens, tiefgrün, in bestimmtem Licht bis hellgrün variierend; die Federn von einer plüschartigen Textur; die am hinteren Teil des Halses sind lang, spitz und wie eine Mähne, aber am Kinn und am Hals ähneln sie denen auf dem Scheitel, und beide erscheinen in bestimmtem Licht schuppig, entweder Indigo oder Grün, und glänzend wie Metall; Auf jeder Seite des Halses befindet sich ein blauer Streifen, der das Grün oben und unten teilt und nach vorne zur Brust kommt, wo er einen weiten Raum einnimmt; in der Mitte des Scheitels stehen vier Borsten, die fast zwei Zoll lang sind und nach hinten tendieren; oberer Teil des Rückens und Flügel, grünlich schwarz, in bestimmtem Licht, ziemlich schwarz erscheinend; von der Brust bis zum Rumpf tief, matt aschefarben; Schwanz gerade am Ende und drei Zoll lang, die beiden mittleren Federn mattgrün, spitz; die anderen sind innen dunkel und auf den Außenfahnen grün, und alle krümmen sich ein wenig nach außen; Beine beschuppt; Krallen schwarz und gebogen, wenn auch nicht sehr kräftig.

Heimatort ungewiss; in der Sammlung von General Davies.”

***

Ich muss gestehen, dass ich keinerlei Ahnung habe womit wir es hier zu tun haben könnten, es könnte sich tatsächlich um einen Paradiesvogel(hybriden) handeln oder aber auch um einen vollkommen anderen Vogel, z. B. eine Starenart; am wahrscheinlichsten aber haben wir es hier mit einem der damals offenbar gar nicht so selten anzutreffenden Fälschungen zu tun, die aus allerlei Vogelteilen zusammengebaut und an den meistbietenden Kuriositätensammler verschachert wurden.

*********************

*********************

Quelle:

[1] John Latham: A general history of birds. Winchester: printed by Jacob and Johnson, for the author: — sold in London by G. and W. B. Whittaker, Ave-Maria-Lane; John Warren, Bond-Street, W. Wood, 428; and J. Mawman, 39, Ludgate-Street 1821-1828

*********************

bearbeitet: 25.03.2021

Schöner Hartschnabel (Sparactes superbus (Shaw))

“Von der Größe einer Drossel; der ganze obere Theil des Körpers schwarz, mit Ausnahme des Bürzels und der obern Deckfedern des Schwanzes, welche gelbgrünlich sind. Auf dem Kopfe steht ein vier Zoll langer Federbush aus zerschlissenen Federn bestehend, welche gegen den Schnabel gekehrt sind; die Kehle ist mit steifen Borsten besezt und lebhaft roth, mit einigen gelblichen Flecken nach unten; Brust und Bauch schwarz; über die Brust läuft ein Gürtel von lebhaftem Gelb, mit rothen Streifen, und an den Seiten mit schwarzen Punkten; der Schnabel ist eisengrau, die Füße blaulich und die Nägel schwarz.

Das Vaterland dieses Vogels ist unbekannt, das einzig vorhandene Exemplar wurde von Vaillant beschrieben und bekannt gemacht. Man will aber entdeckt haben, daß es ein künstlich zusammengesetzter Vogel sey, womit dann freilich diese Gattung ganz wegfallen würde.” [1]

***

Wie so viele nicht näher miteinander verwandte Vogelformen wurde auch diese zuerst einmal als eine Art Würger (Laniidae) beschrieben später aber unter anderem den Kuckucksvögeln (Cuculidae) zugeordnet, vielleicht aufgrund der zygodactylen Füße, die in den mir bekannten Abbildungen aber anisodactyl dargestellt wurden.

Bereits zu Beginn das 19. Jahrhunderts wurde dieser Vogel als eine Fälschung erkannt, vermutlich diente ein Senegal-Furchenschnabel (Lybius dubius (Gmelin)) als Ausgangsmaterial, ein Vogel also, der, obwohl er tatsächlich existiert, eigentlich schon absonderlich und unecht genug wirkt.

*********************

***

Witzigerweise findet die hier gezeigte Abbildung auch auf der Wikipedia-Seite über den Braun-Haubendickkopf (Ornorectes cristatus (Salvadori)) Verwendung, einer Vogelart, die tatsächlich existiert und vollkommen anders aussieht.

*********************

Quelle:

[1] H. R. Schinz; Joseph Brodtmann: Naturgeschichte und Abbildungen der Vögel: nach den neuesten Systemen bearbeitet. Leipzig: Weidmann’sche Buchhandlung 1836

*********************

bearbeitet: 23.03.2021

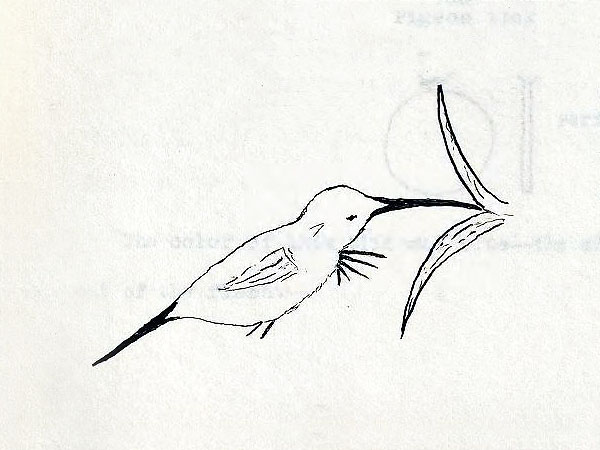

Karmesintaube (Columba rosea Miller & Shaw)

“Unter all dem schönen Hausgeflügel, welches uns Indien geliefert hat, ist die köstliche Karmesintaube gewiss der prächtigste Vogel. Sie ist eine Haustaube, und ohngefähr so gross wie die unsrigen. Ihr Gefieder ist hauptsächlich ein glänzendes Karmesin, welches sich an mehreren Stellen in ein schönes Rosenroth verläuft. Die Kehle, Scheitel, Augenkreise und Spitzen der Flügelfedern sind weiss, die Schwung- und Schwanzfedern aber braun. Die Ostindier halten diese prächtige Taube häufig für ihre schönen Hühnerhöfe.“

Dieser Text stammt aus einem Kinderbuch und behandelt eine der eigenartigsten mysteriösen Vogelformen überhaupt; tatsächlich taucht ihr Name immer einmal wieder in Auflistungen ausgestorbener Vogelarten auf – trotzdem hat sie jedoch wohl nie existiert.

Im 18. Jahrhundert war es keinesfalls selten in diversen wissenschaftlichen Schriften, und zwar nicht nur solchen für Kinder, allerlei ausgedachtes, mehr oder weniger fantastisch anmutendes unterzubringen um die geneigte Leserschaft angemessen zu unterhalten, darunter eben auch komplett ausgedachte Tierarten.

*********************

*********************

Quellen:

[1] F. J. Bertuch: Bilderbuch Für Kinder: enthaltend eine angenehme Sammlung von Thieren, Pflanzen, Blumen, Früchten, Mineralien, Trachten und allerhand andern unterrichtenden Gegenständen aus dem Reiche der Natur, der Künste und Wissenschaften; alle nach den besten Originalen gewählt, gestochen, und mit einer kurzen wissenschaftlichen, und den Verstandes-Kräften eines Kindes angemessenen Erklärung begleitet. Weimar, im Verlage des Industrie-Comptoirs 1802

[2] Pauline Knip: Les pigeons, par Madame Knip, née Pauline de Courcelles, le texte par C. J. Themminck. Paris: chez Mme. Knip 1838-1843

[3] Julian P. Hume: Extinct Birds. Bloomsbury Natural History; 2nd edition 2017

*********************

bearbeitet: 22.03.2021

San Domingo-Taube (Columba dominicensis Latham)

“Cette jolie espèce, dont Buffon a donné le premier une figure très exacte, habite, avec l’espèce du précédent article, les contrées méridionales du nouveau continent. Nous ne connoissons de cette Colombe que l’extérieur, dont nous donnerons une description succincte. La longueur totale de la Colombe à Moustache est de onze pouces; la queue est moins longue que dans les espèces dont nous venons de parler; elle est cependant à pennes d’inégale longueur, et présente la forme d’un cône. Le front et la région des yeux sont blancs; la gorge l’est aussi. Cette couleur se dirige sur une partie des côtés du cou, et se joint sur la nuque. Sur le haut de la tête est une large bande transversale noire, qui semble la partager en deux parties. De la base du bec se dirige, en passant sous les yeux, une moustache noire qui s’élargit vers son extrémité, et dont les plumes recouvrent l’orifice des oreilles: un large collier noir entoure le cou vers le milieu de sa longueur. La poitrine est de couleur vineuse; mais vers les parties latérales il y a des plumes pourprées à reflets métalliques: toutes les parties supérieures sont d’un brun-terreux. Sur les plumes scapulaires et les grandes couvertures sont quelques taches noires. Les rémiges sont noirâtres, bordées extérieurement de gris-blanc. Le ventre est brun-cendré; les pennes de la queue sont grises; toutes, excepté les deux du milieu, ont leur extrémité blanche: le bec est noir, et les pieds sont rougeâtres.

On trouve l’espèce à Saint-Domingue, et probablement aussi dans les autres parties de l’Amérique méridionale situées sous le même degré. Nous présumons que l’individu figuré par nous à cet article est le mâle de l’espèce: nous ne saurions cependant raffirmer. Le seul individu que nous ayons eu occasion de voir faisoit autrefois partie du Muséum Leverian, à Londres.” [1]

Übersetzung:

“Diese hübsche Art, von der Buffon als erster eine sehr genaue Abbildung lieferte, lebt zusammen mit der Art im vorherigen Artikel in den südlichen Regionen des neuen Kontinents. Wir kennen von dieser Taube nur das Äußere, von dem wir eine kurze Beschreibung geben werden. Die Gesamtlänge der Schnurrbarttaube beträgt elf Zoll [ca. 28 cm];der Schwanz ist kürzer als bei der gerade erwähnten Art; er besitzt jedoch Federn von ungleicher Länge und hat die Form eines Kegels. Stirn und Augenpartie sind weiß; der Hals auch. Diese Farbe verläuft an einem Teil der Seiten des Halses und verbindet sich im Nacken. Auf der Oberseite des Kopfes befindet sich ein breites schwarzes Querband, das ihn in zwei Teile zu teilen scheint. Von der Basis des Schnabels verläuft unter den Augen ein schwarzer Schnurrbart, der sich zum Ende hin erweitert und dessen Federn die Öffnung der Ohren bedecken: Ein großer schwarzer Kragen umgibt den Hals zur Mitte seiner Länge. Die Brust hat eine weinrote Farbe; aber zu den Seiten hin gibt es lila Federn mit metallischem Schimmer: Alle oberen Teile sind erdbraun. Auf den Schulter- und den größeren Flügeldecken befinden sich einige schwarze Flecken. Die Flugfedern sind schwärzlich und außen grauweiß eingefasst. Der Bauch ist aschbraun, die Schwanzfedern sind grau; Alle außer den beiden in der Mitte haben weiße Spitzen: Der Schnabel ist schwarz und die Füße rötlich.

Die Art kommt in Santo Domingo [Haiti/Hispaniola] und wahrscheinlich auch in anderen Teilen Südamerikas unter dem gleichen Grad vor. Wir gehen davon aus, dass das von uns in diesem Artikel vorgestellte Individuum das Männchen der Art ist. Dies können wir jedoch nicht bestätigen. Das einzige Individuum, das wir sehen konnten, war früher Teil des Leverian Museum in London.“

***

Diese ‘Art’ ist ursprünglich anhand einer Darstellung aus dem Jahr 1771bekannt, die dann wiederum als Vorlage für eine Beschreibung durch John Latham im Jahr 1790 diente und eben offenbar auch der oben wiedergegebenen aus dem 19. Jahrhundert. [2]

Interessant finde ich allerdings die Aussage der Autoren (Temminck und Knip) ein Exemplar gesehen haben zu wollen, das vormals Bestandteil der ehemaligen Leverianischen Sammlung in Leicester House in Westminster, London gewesen sein soll; außerdem fällt beim Lesen der Beschreibung auf, dass sie nicht so ganz zu der dazugehörigen Darstellung passen möchte.

*********************

*********************

Quellen:

[1] Pauline Knip: Les pigeons, par Madame Knip, née Pauline de Courcelles, le texte par C. J. Themminck. Paris: chez Mme. Knip 1838-1843

[2] Julian P. Hume: Extinct Birds. Bloomsbury Natural History; 2nd edition 2017

*********************

bearbeitet: 22.03.2021

Azurtaube (Columba dorsocaerulea Temminck & Knip)

“Toutes les parties supérieures de cette jolie Colombe étant d’une brillante et vive couleur d’azur, nous en avons tiré son signalement spécifique. On nous a assuré que l’espèce habite au Bengale; ce dont nous ne saurions cependant garantir l’authenticité.

La longueur totale de la Colombe azurée est de neuf pouces; ses ailes atteignent à la moitié de la longueur de la queue, qui est arrondie.

Un bleu céleste ou couleur de turquoise orientale est répandu sur les parties supérieures; les joues et la gorge sont d’un blanc pur. On remarque sur le devant du cou et de la poitrine des teintes d’un brun fauve, nuancé d’un ton vineux; le ventre et l’abdomen sont blanchâtres; les pieds et le cercle nu qui enture les yeux sont rouges; la base du bec est rougèatre, mais la ointe est d’un blanc jaunâtre.

Un individu de cette belle espèce faisoit partie du cabinet de M. Holthuysen, à Amsterdam.” [1]

Übersetzung:

“Alle oberen Teile dieser hübschen Taube haben eine brillante und lebendige azurblaue Farbe, wir haben daraus ihre spezifische Beschreibung gezogen. Uns wurde versichert, dass die Art in Bengalen lebt, wir können jedoch die Echtheit nicht garantieren.

Die Gesamtlänge der Azurtaube beträgt 9 Zoll [ca. 23 cm]; ihre Flügel erreichen die halbe Länge des Schwanzes, der abgerundet ist.

Ein himmlisches Blau oder orientalisches Türkis ist auf den oberen Teilen verteilt; die Wangen und der Hals sind rein weiß. Man bemerkt auf der Vorderseite des Halses und auf der Brust ein Rehbraun, nuanciert mit einem weinroten Ton; die Brust und der Bauch sind weißlich; die Füße und der nackte Ring um die Augen sind rot; die Basis des Schnabels ist rötlich, aber die Schnabelspitze ist gelblich weiß.

Ein Individuum dieser schönen Art befand sich im Kabinett von Herrn Holthuysen in Amsterdam.“

Ich kann nicht wirklich sagen, was ich mit diesem Vogel anfangen soll, mit ziemlicher Sicherheit stammt er nicht aus Bengalen (im Nordosten Indiens) und mit ebenso ziemlicher Sicherheit handelt es sich bei dem (einzigen existierenden?) Exemplar im Kabinett des Herrn Holthuysen in Amsterdam um eine der damals nicht unüblichen gefälschten Stopfpräparate, die, wenn sie besonders gelungen waren, für durchaus nicht wenig Geld an interessierte Sammler seltener Schätze gebracht wurden.

Doch, da jenes Originalexemplar nicht mehr existiert, handelte es sich hierbei um eine gewöhnliche, eingefärbte Taube oder um einen vollkommen anderen Vogel, dem ein Taubenköpfchen aufgesetzt wurde? Dies werden wir wahrscheinlich nie erfahren.

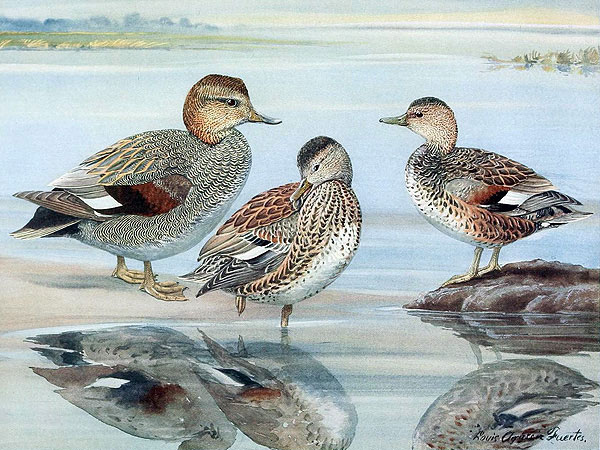

Es existieren auch Versionen dieses Gemäldes auf denen die weinroten Gefiederbereiche komplett grau und die Beine sehr blass, fast weißlich gefärbt sind.

*********************

Quelle:

[1] Pauline Knip: Les pigeons, par Madame Knip, née Pauline de Courcelles, le texte par C. J. Themminck. Paris: chez Mme. Knip 1838-1843

*********************

bearbeitet: 21.03.2021

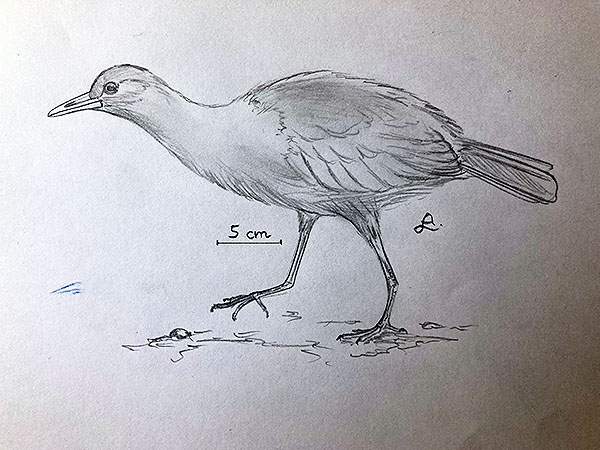

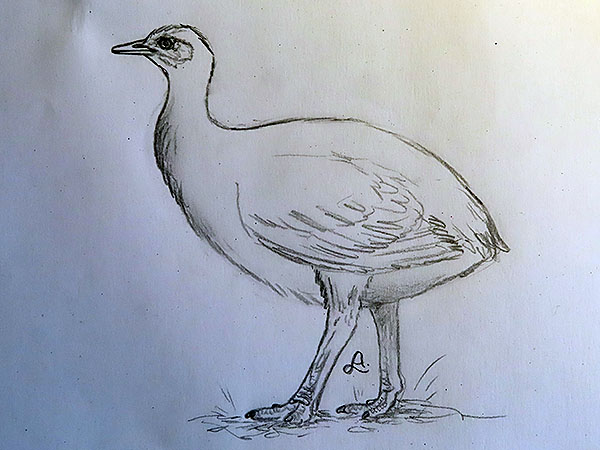

Nauru-Ralle (Gallirallus sp.)

Nauru; die gesamte Insel war einst mit einem Substrat bedeckt, das zu großen Teilen aus Guano bestand, und vollkommen bewaldet.

Heute sieht sie so aus, eine raue und trostlose Karstlandschaft, die nicht natürlichen Ursprungs ist sondern menschgemacht.:

*********************

***

“Es gibt auch Vögel auf Nauru, wie Fregattvogel, schwarze Seeschwalbe, weiße Seeschwalbe, Regenpfeifer, Brachvogel, Möve, Schnepfe, Uferläufer, Ralle, Lachmöve und Rohrdrossel.” [1]

“Die Vogelwelt ist nach Zahl und Art reicher. Der Fregattvogel (Tachypetes aquila), itsi, die schwarze Seeschwalbe (Anous), doror, die weiße Seeschwalbe (Gygis), dagiagia, werden als Haustiere gehalten; der erste galt früher als heiliger Vogel, mit den beiden anderen werden Kampfspiele veranstaltet. Am Strande trifft man den Steinwälzer (Strepsilas interpres), dagiduba, den Regenpfeifer (Numenius), den Uferläufer (Tringoides), ibibito, die Schnepfe, ikirer, den Brachvogel ikiuoi, den Strandreiter iuji, die Ralle, earero bauo und zwei Möwenarten (Sterna), igogora und ederakui. Im Busche beobachtet man an den Blüten der Kokospalme den kleinen Honigsauger raigide, die Rohrdrossel (Calamoherpe syrinx), itirir und den Fliegenschnäpper (Rhipidura), temarubi.” [1]

***

Diese beiden knappen Aufzählungen sind alles was von der ehemaligen Existenz einer Rallenart auf der Insel Nauru kündigt, und offiziell wird dieser Bericht denn auch als nicht vertrauenswürdig abgetan [3], dabei ist gerade das ehemalige Vorkommen einer Rallenart auf Nauru geradezu zweifelsfrei sicher.

Die Familie der Rallen ist führend im Besiedeln selbst der entlegensten Inseln, und anhand von archäologischen und paläontologischen Ausgrabungen ist heute bekannt, dass es innerhalb von Mikronesien weitaus mehr Rallenarten gab als die wenigen, die bis ins 20. Jahrhundert überlebt haben (in der Gattung Gallirallus sind dies genau zwei, die Guam-Ralle (Gallirallus owstoni (Rothschild)) und die Wake-Ralle (Gallirallus wakensis (Rothschild))). [2]

Das Vorkommen einer solchen endemischen Form auf Nauru ist daher geradezu absolut sicher.

*********************

Quellen:

[1] Paul Hambruch: Nauru. Ergebnisse der Südsee-Expedition 1908-1910. II. Ethnographie: B. Mikronesien, Band 1.1 Halbband. Hamburg, Friedrichsen 1914

[2] David W. Steadman: Extinction and Biogeography of Tropical Pacific Birds. University of Chicago Press 2006

[3] Donald W. Buden: The birds of Nauru. Notornis 55: 8-19. 2008

*********************

bearbeitet: 20.03.2021

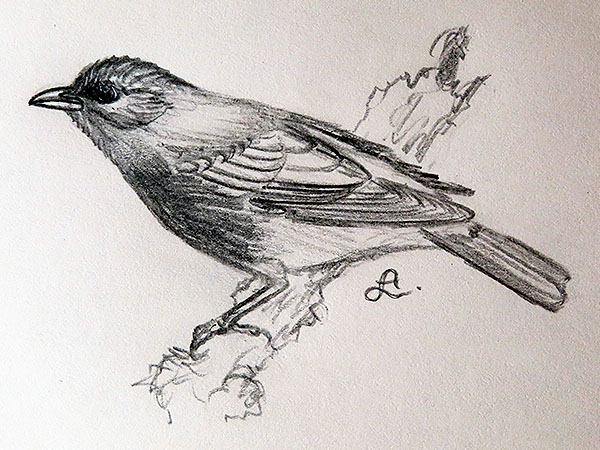

Nauru-Fächerschwanz (Rhipidura sp.)

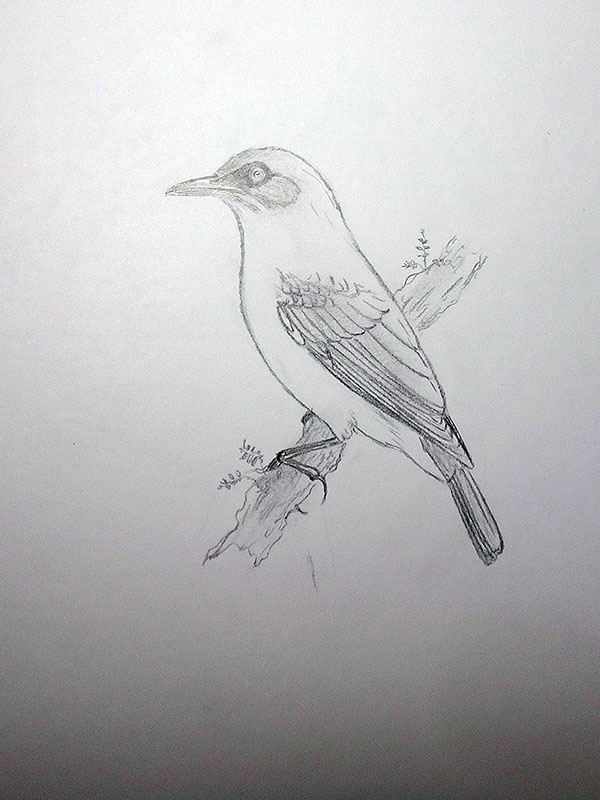

Mikronesien beherbergt heute noch drei Arten von Fächerschwänzen, den Pohnpei-Fächerschwanz (Rhipidura kubaryi Finsch), den Palau-Fächerschwanz (Rhipidura lepida Hartlaub & Finsch) sowie den Fuchsfächerschwanz (Rhipidura rufifrons (Latham)), der mit einigen Unterarten die Marianen bewohnt.

Es mag vormals durchaus mehr Formen gegeben haben ….

Der einzige Hinweis auf des ehemalige Vorkommen einer Fächerschwanzart auf der isolierten Insel Nauru ist der Bericht des Ethnologen Paul Hambruch aus dem Jahr 1910, der wiederum Erzählungen aufgeschrieben hat, die ihm von einem Einheimischen der Insel erzählt wurden.:

“Die Vogelwelt ist nach Zahl und Art reicher. Der Fregattvogel (Tachypetes aquila), itsi, die schwarze Seeschwalbe (Anous), doror, die weiße Seeschwalbe (Gygis), dagiagia, werden als Haustiere gehalten; der erste galt früher als heiliger Vogel, mit den beiden anderen werden Kampfspiele veranstaltet. Am Strande trifft man den Steinwälzer (Strepsilas interpres), dagiduba, den Regenpfeifer (Numenius), den Uferläufer (Tringoides), ibibito, die Schnepfe, ikirer, den Brachvogel ikiuoi, den Strandreiter iuji, die Ralle, earero bauo und zwei Möwenarten (Sterna), igogora und ederakui. Im Busche beobachtet man an den Blüten der Kokospalme den kleinen Honigsauger raigide, die Rohrdrossel (Calamoherpe syrinx), itirir und den Fliegenschnäpper (Rhipidura), temarubi.” [1]

***

Dieser Bericht wird offiziell als unwahrscheinlich abgelehnt [3], was ich persönlich nicht verstehe, denn er erscheint mir durchaus zuverlässig, selbst wenn es die dort aufgezählten Vögel zu der Zeit bereits nicht mehr gegeben haben sollte, so können die Überlieferungen durchaus länger überdauert haben.

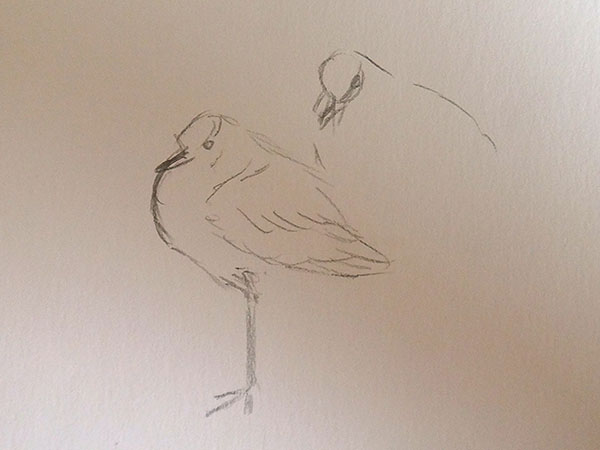

Das Foto zeigt den Pohnpei-Fächerschwanz von der gleichnamigen Insel.

***

Es ist erstaunlich, dass auch die Inseln Chuuk und Yap offenbar keine einheimischen Fächerschwanzarten beherbergen – hier geht man für gewöhnlich oft davon aus, dass es solche Arten durchaus vormals gegeben haben dürfte, dass sie aber schon bald nach der Besiedlung durch Menschen ausgestorben sind. [2]

*********************

*********************

Quellen:

[1] Paul Hambruch: Nauru. Ergebnisse der Südsee-Expedition 1908-1910. II. Ethnographie: B. Mikronesien, Band 1.1 Halbband. Hamburg, Friedrichsen 1914

[2] David W. Steadman: Extinction and Biogeography of Tropical Pacific Birds. University of Chicago Press 2006

[3] Donald W. Buden: The birds of Nauru. Notornis 55: 8-19. 2008

*********************

bearbeitet: 20.03.2021

Nauru-Honigfresser (Myzomela sp.)

Diese Art (oder Unterart) mag auf der Insel Nauru vorgekommen sein, sie wird allerdings offenbar in nur einem einzigen Bericht erwähnt, und dabei handelt es sich um Erzählungen aus zweiter Hand.

Paul Hambruch, der Enthnologe der zu Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts das Leben der Einwohner der Insel Nauru erforschte erwähnt in seinem Bericht Geschichten, die ihm von einem Einheimischen namens Auuiyeda erzählt wurden und in denen unter anderem auch von den einheimischen Vögeln die Rede ist.:

“Die Vogelwelt ist nach Zahl und Art reicher. Der Fregattvogel (Tachypetes aquila), itsi, die schwarze Seeschwalbe (Anous), doror, die weiße Seeschwalbe (Gygis), dagiagia, werden als Haustiere gehalten; der erste galt früher als heiliger Vogel, mit den beiden anderen werden Kampfspiele veranstaltet. Am Strande trifft man den Steinwälzer (Strepsilas interpres), dagiduba, den Regenpfeifer (Numenius), den Uferläufer (Tringoides), ibibito, die Schnepfe, ikirer, den Brachvogel ikiuoi, den Strandreiter iuji, die Ralle, earero bauo und zwei Möwenarten (Sterna), igogora und ederakui. Im Busche beobachtet man an den Blüten der Kokospalme den kleinen Honigsauger raigide, die Rohrdrossel (Calamoherpe syrinx), itirir und den Fliegenschnäpper (Rhipidura), temarubi.” [1]

***

Seltsamerweise gilt der Bericht als unglaubwürdig [2], was ich persönlich überhaupt nicht verstehe, denn die drei hier genannten Vogelformen (eine Ralle, ein Honigfresser und ein Fächerschwanz) sind sehr wohl aus Mikronesien bekannt und kommen bzw. kamen auf etlichen der Inseln vor.

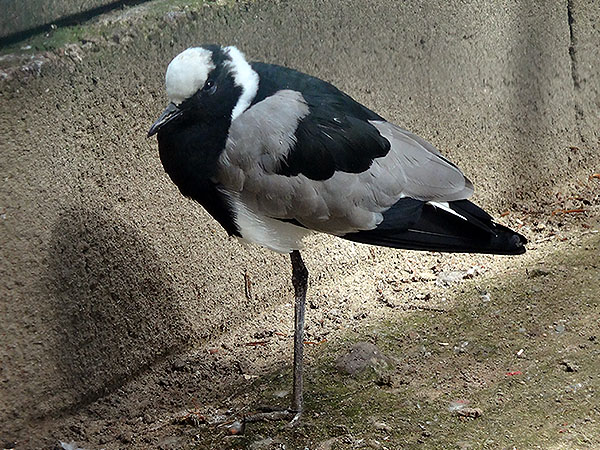

Im Falle dieses Honigfressers mag es sich, der doch recht isolierten Lage Naurus entsprechend, um eine eigenständige Art gehandelt haben oder aber um eine Unterart des Mikronesischen Honigfressers (Myzomela rubratra (Lesson)) (siehe Foto), der in Mikronesien mit vier Unterarten verbreitet und dort eigentlich auch überall recht häufig ist.

Der Nauru-Honigfresser verschwand vermutlich aufgrund von Bejagung (der roten Federn wegen aber auch weil diese Vögel in ihrer Heimat als Delikatesse gelten) sowie in Folge der nahezu kompletten Zerstörung der Vegetation durch den massiven Guano/Phosphat-Abbau, der auf Nauru stattfand.

*********************

*********************

Quellen:

[1] Paul Hambruch: Nauru. Ergebnisse der Südsee-Expedition 1908-1910. II. Ethnographie: B. Mikronesien, Band 1.1 Halbband. Hamburg, Friedrichsen 1914

[2] Donald W. Buden: The birds of Nauru. Notornis 55: 8-19. 2008

*********************

bearbeitet: 20.03.2021

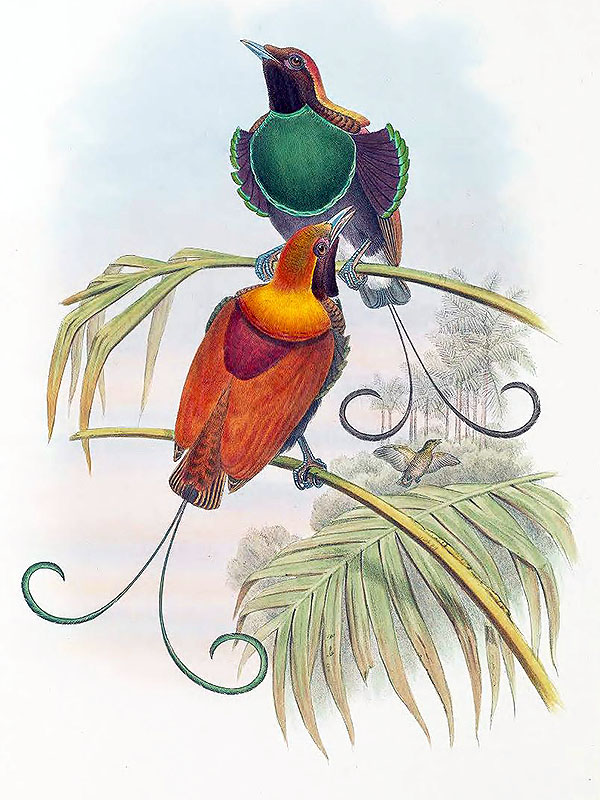

Wilhelmina-Paradiesvogel (Lamprothorax wilhelminae Meyer)

Der Wilhelmina-Paradiesvogel ist eine jener Paradiesvogel’arten’, die nach einem Mitglied eines der zahlreichen europäischen Königshäuser benannt wurde – in diesem Fall war dies die damalige niederländische Königin (Wilhelmina Helena Pauline Maria von Oranien-Nassau (Königin Wilhelmina 1880-1962)).

Die ‘Art’ ist nur anhand von drei (männlichen) Exemplaren bekannt, und es ist diese Tatsache, dass nahezu alle jene ‘lost birds of paradise’ [1] nur anhand männlicher Exemplare bekannt sind, die einem zu denken geben sollte. Würde es sich tatsächlich um heute ausgestorbene Arten handeln, so wären sicher einige dazugehörigen Weibchen gefunden wurden, dem ist aber nicht so, in keinem einzigen Fall! (… in den beiden Fällen in denen eine solche Form anhand eines Weibchens bekannt ist, fehlen wiederum die passenden Männchen ….)

***

Es handelt sich auch hier um eine Hybridform, und zwar mit dem Sichelschwanz-Paradiesvogel (Cicinnurus magnificus (J. R. Forst.)) und dem Kragenparadiesvogel (Lophorina superba J. R. Forst) als Elternarten. [2]

*********************

*********************

Quellen:

[1] Errol Fuller: The Lost Birds of Paradise. Airlife 1996

[2] Clifford B. Frith; Bruce M. Beehler: The Birds of Paradise: Paradisaeidae. Oxford University Press 1998

*********************

bearbeitet: 20.03.2021

Rothschilds Lappenschnabel-Paradiesvogel (Loboramphus nobilis Rothschild)

Dieser außerordentlich schöne Vogel wurde im Jahre 1901 als eigenständige Art beschrieben, nur ein einziges Exemplar ist bekannt.

Es handelt sich wohl um eine der außergewöhnlichsten Hybriden überhaupt, eine Kreuzung zweier ungemein unterschiedlicher Arten, nämlich dem Kragenparadiesvogel (Lophorina superba J. R. Forst) und der Langschwanz-Paradigalla (Paradigalla carunculata Lesson); dies ist jedoch nicht hundertprozentig klar. [1]

Einige Ornithologen halten diese Form nach wie vor für eine eigenständige, heute ausgestorbene Art.

*********************

*********************

Quelle:

[1] Clifford B. Frith; Bruce M. Beehler: The Birds of Paradise: Paradisaeidae. Oxford University Press 1998

*********************

bearbeitet: 20.03.2021

Wundervoller Paradiesvogel (Paradisaea mirabilis Reichenow)

Der Wundervolle Paradiesvogel, der ‘Wonderful Bird of Paradise’, ist anhand von ganzen fünf (männlichen) Exemplaren bekannt, es handelt sich hierbei um die ziemlich unwahrscheinliche und trotzdem geschehene Kreuzung zwischen dem Kleinen Paradiesvogel (Paradisaea minor Shaw) und dem Fadenhopf (Seleucidis melanoleuca (Daudin)).

Diese beiden durchaus unterschiedlich aussehenden Arten, ja Gattungen, haben einen prachtvollen Mix aus beiden Elternteilen hervorgebracht, dem die hier gezeigte Darstellung nicht ansatzweise gerecht wird.

*********************

*********************

Quelle:

[1] Clifford B. Frith; Bruce M. Beehler: The Birds of Paradise: Paradisaeidae. Oxford University Press 1998

*********************

bearbeitet: 14.03.2021

Waigiou-Paradiesvogel (Diphyllodes gulielmi III Meyer)

Der Waigiou-Paradiesvogel, sicher besser bekannt unter dem englischen Namen ‘King of Holland’s Bird of Paradise’, ist eine der am häufigsten auftauchenden Hybridformen innerhalb der Familie.

Es war im 19. Jahrhundert Mode neu entdeckte Paradiesvögel nach Mitgliedern diverser europäischer Königshäuser zu benennen, so wurde diese Form nach dem damaligen holländischen König (Wilhelm Alexander Paul Friedrich Ludwig von Oranien-Nassau (König Wilhelm III 1817-1890)) benannt.

Es handelt sich hierbei um eine offenbar häufiger auftretende Kreuzung der äußerlich so verschiedenen und doch nah verwandten Arten Sichelschwanz-Paradiesvogel (Cicinnurus magnificus (J. R. Forst.)) und Königsparadiesvogel (Cicinnurus regius (L.)), offenbar mit anschließender Rückkreuzung mit der ersteren Art.

***

Im Gegensatz zu den meisten anderen Paradiesvogelhybriden kann man diesem hier die beiden Elternarten sehr gut ansehen.

*********************

*********************

Quellen:

[1] Clifford B. Frith; Bruce M. Beehler: The Birds of Paradise: Paradisaeidae. Oxford University Press 1998

*********************

bearbeitet: 14.03.2021

********************

bearbeitet: 14.03.2021

*********************

bearbeitet: 20.01.2021

*********************

bearbeitet: 13.01.2021

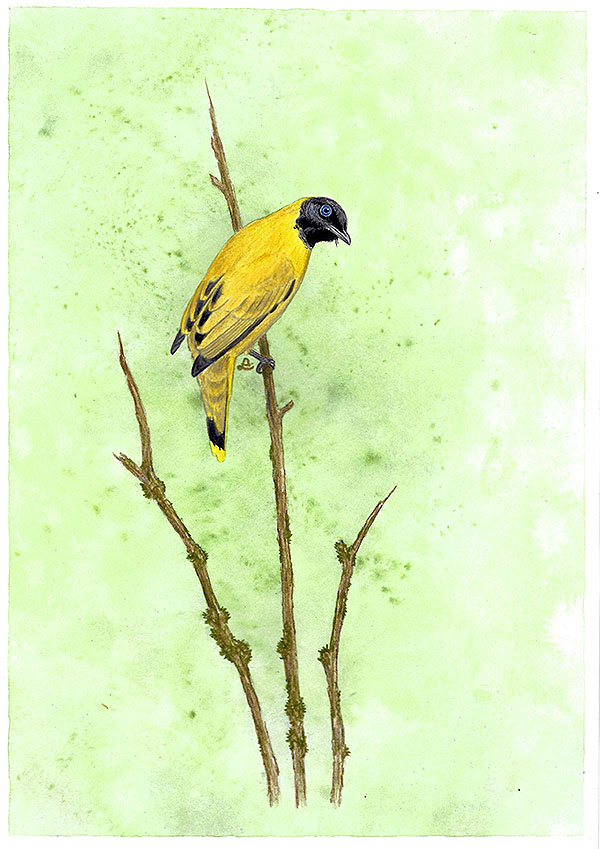

The Black-headed Bulbul is a typical representative of the bulbuls; it comes from Southeast Asia, where it occurs with four subspecies from northeast India, Malaysia and Thailand to Borneo, Java, and Sumatra in Indonesia.

The species reaches a size of about 17 cm.

The picture shows the nominate form, which is widespread on the Southeast Asian mainland, there are three color morphs, in addition to the most common one shown here, there is one in which the yellow and green are completely replaced by gray and one with a gray basic coloration in which at least the wings are colored yellow.

*********************

*********************

edited: 20.07.2023

Ich habe hier ja schon mehrfach über oligozäne Vögel mit offenbar brüchigen Gliedmaßen gesprochen ….

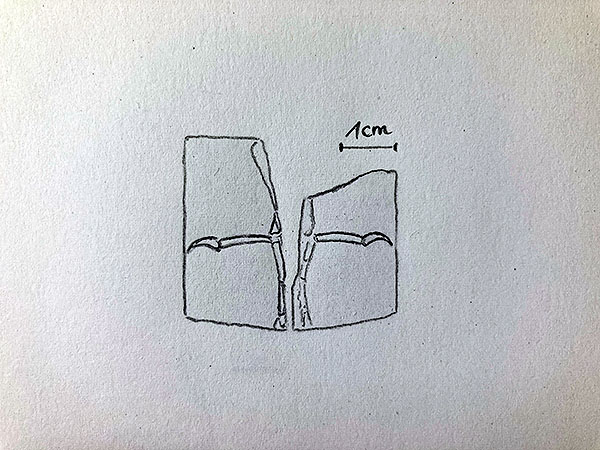

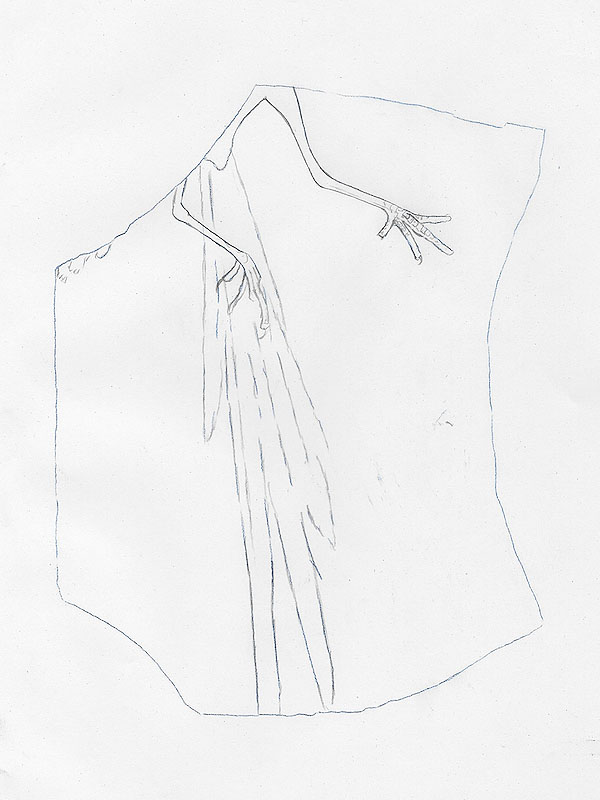

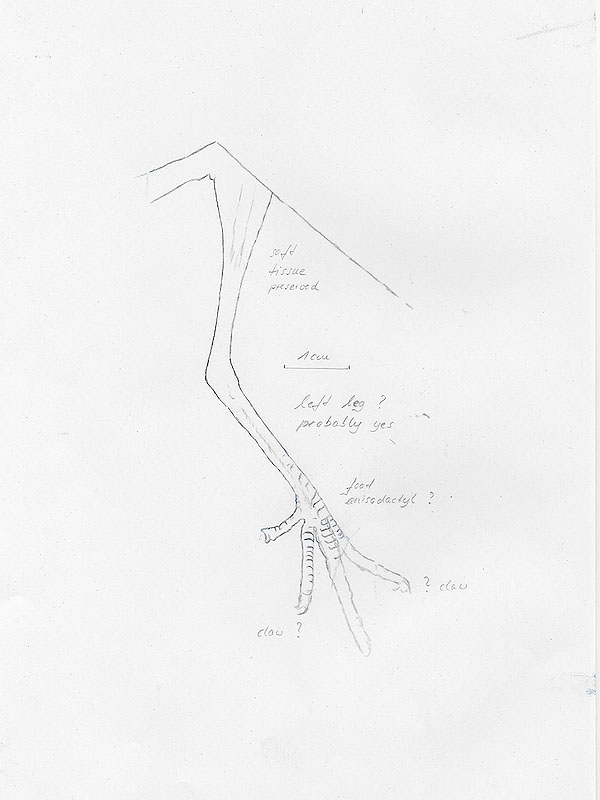

Dieser hier ist ein winziges Fossil, bestehend aus einer Platte und deren Gegenplatte (Positivplatte und Negativplatte?), und besteht aus einem einzelnen Fuß, einem ca. 3,6 cm langen, rechten Fuß, an dem obendrein auch nur der erste und der zweite Zeh erhalten geblieben sind.

Dieser Teilfuß wurde mit diversen anderen Vogelformen verglichen und weist die größten Übereinstimmungen mit den Taubenvögeln (Columbiformes) auf, so dass es sich hierbei eventuell tatsächlich um den Fuß einer fossilen Taube handeln könnte – es wäre dies dann die älteste bislang bekannte Taubenform. Die ältesten bis dahin bekannten Taubenfossilien stammen aus dem Miozän bzw. der Grenze zwischen dem Oberoligozän und dem Untermiozän, sie erinnern durchweg an moderne Formen und lassen sich oft auch heutigen Linien innerhalb der Columbiformes zuordnen.

Wie dem auch sei, ZPALWr. A/4003 ist nur in Teilen erhalten, so dass eine genauere Bestimmung erst wirklich möglich ist wenn weitere Funde auftauchen sollten. [1]

Sollte es sich hierbei tatsächlich um eine echte Taubenform handeln, so lässt sich deren Größe auf etwa 25 cm schätzen.

*********************

Quelle:

[1] Zbigniew M. Bocheński; Teresa Tomek; Ewa Świdnicka: A columbid-like avian foot from the Oligocene of Poland. Acta Ornithologica 45(2): 233-236. 2010

*********************

bearbeitet: 26.12.2020

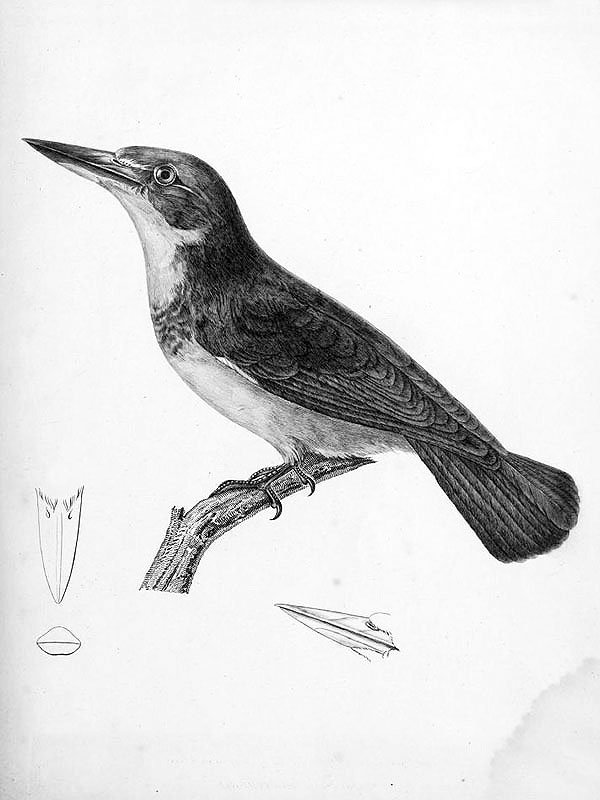

Die Art wird von den Autoren der Gruppe der Tyrannida zugeordnet, einer Gruppe von suboscinen Passeriformes, die heute ausschließlich in Süd- und mit einigen wenigen Arten auch in Nordamerika verbreitet ist und weist hier die größten Gemeinsamkeiten mit den Schnurrvögeln (Pipridae) auf. [2]

Die Tyrannida haben sich jedoch, so wird vermutet, auf den amerikanischen Kontinenten entwickelt, und zwar so ziemlich ungestört seit wohl bereits ca. 64 Millionen Jahren, also zu Beginn des Paläozän. Demnach wäre die Zuordnung dieses oligozänen Vogels aus Europa zu den Tyrannida doch etwas fraglich. [1]

Vielleicht handelt es sich hierbei um eine komplett ausgestorbene Linie von Pipra-ähnlichen suboscinen Vögeln, die später in Europa durch oscine Arten verdrängt wurden.

Es ist sehr ungewöhnlich, dass NT-LBR-014, trotz seiner äußerst guten Erhaltung, von den Autoren keinen Namen erhalten hat.

*********************

Quellen:

[1] John Reilly: The Ascent of Birds: how modern science is revealing their story. PELAGIC PUB LTD 2018

[2] Ségolène Riamon; Nicolas Tourment; Antoine Louchart: The earliest Tyrannida (Aves, Passeriformes), from the Oligocene of France. Scientific Reports 10(9776): 1-14. 2020

*********************

bearbeitet: 25.12.2020

*********************

Quelle:

[1] Andrea Cau: Falcatakely: eterodossia e pluralismo nell’Anno di Oculudentavis. Theropoda. 27 Novembre 2020

[2] Mickey Mortimer: Is Falcatakely a bird? The Theropod Database Blog. November 28, 2020

[3] Patrick O’Connor; Alan H. Turner; Joseph R. Groenke; Ryan N. Felice; Raymond R. Rogers; David W. Krause; Lydia J. Rahantarisoa: Late Cretacous bird from Madagascar reveals unique development of beaks. Nature. 2020 Nov 25. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2945-x.

*********************

bearbeitet: 28.11.2020

This little feather comes from an Elephant-foot Moa (Pachyornis elephantopus (Owen)), which was found on the South Island of New Zealand and was exterminated about 600 to 500 years ago through hunting and habitat destruction.

The feather is approx. 3.5 cm long and incomplete, but the original colors have been preserved to this day. [1]

*********************

References:

[1] Nicolas J. Rawlence; Jamie R. Wood; Kyle N. Armstrong; Alan Cooper: DNA content and distribution in ancient feathers and potential to reconstruct the plumage of extinct avian taxa. Proceedings of the Royal Society 276: 3395-3402. 2009

*********************

edited: 21.11.2020

Diese (nicht mehr ganz so) älteste bekannte Feder stammt mit ziemlich großer Wahrscheinlichkeit von dem weltberühmten Urvogel (Archaeopteryx lithographica von Meyer), der tatsächlich aber gar kein wirklicher Vogel im eigentlichen Sinn des Wortes war – aber dies genauer zu erklären überlasse ich Berufs-Paläoornithologen.

Die Feder, bislang erstaunlicherweise einzigartig geblieben, ist etwa 6 cm lang, sie war ziemlich wahrscheinlich sehr dunkel grau bis schwarz gefärbt und stammte wohl aus der Region der Flügeldecken. [1]

*********************

Quelle:

[1] Ryan M. Carney; Helmut Tischlinger; Matthew D. Shawkey: Evidence corrobates identity of isolated fossil feather as a wing covert of Archaeopteryx. Scientific Reports 10: 15593. 2020

*********************

bearbeitet: 15.11.2020

Im Moment beschäftige ich mich mit den Bermudas, einer der entlegensten Insel(gruppe)n und auch eine der Regionen über die nicht nur ich nicht viel weiß ….

Die Bermudas waren einst eine einzige, große Insel; durch den immer wieder ansteigenden und abfallenden Meeresspiegel während des Pleistozän ist die Landmasse aber immer wieder mehr oder weniger vollständig überflutet worden, was einerseits zur Entstehung – andererseits aber auch immer wieder zum Aussterben vieler endemischer Arten geführt hat. Vermutlich haben aber viele der einheimischen Vogelarten viel länger überlebt als allgemein gedacht und sind erst zu Beginn des 17. Jahrhunderts nach der Ankunft der ersten menschlichen Siedler ausgerottet worden.

Das kann man den wenigen zeitgenössischen Berichten entnehmen, wenn man diese denn zu entziffern vermag. 🙂

… ja ja, zeitgenössische Beschreibungen … diese hier stammt von Captain John Smith (derselbe, der in der unfassbar verfälschten Geschichte um die Powhatan-‘Häuptlings’tochter Amonute, besser bekannt als Pocahontas, eine zentrale Rolle spielt) und wurde im Jahr 1623 niedergeschrieben.:

“Birds.

Neither hath the aire for her part been wanting with due supplies of many sorts of Fowles, as the gray and white Hearne, the gray and greene Plover, some wilde Ducks and Malards, Coots and Red-shankes, Sea-wigions, Gray-bitterns, Cormorants, numbers of small Birds like Sparrowes and Robins, which have lately beene destroyed by the wilde Cats, Wood-pickars, very many Crowes, which since this Plantation are kild, the rest fled or seldome seene except in the most uninhabited places, from whence they are observed to take their flight about sun set, directing their course towards the North-west, which makes many coniecture there are some more Ilands not far off that way. Sometimes are also seene Falcons & Jar-falcons, Ospraies, a Bird like a Hobby, but because they come seldome, they are held but as passengers; but above all these, most deserving observation and respect are those two sorts of Birds, the one for the tune of his voice, the other for the effect, called the Cahow, and Egge bird, which on the first of May, a day constantly observed, fall a laying infinite store of Eggs neere as big as Hens, upon certaine small sandie baies especially in Coupers Ile; and although men sit downe amongst them when hundreds have bin gathered in a morning, yet there is hath stayed amongst them till they have gathered as many more: they continue this course till Midsummer, and so tame & feareles, you must thrust them off from their Eggs with your hand; then they grow so faint with laying, they suffer them to breed & take infinite numbers of their young to eat, which are very excellent meat.” [1]

Ich habe versucht, dieses etwas kauderwelschige Englisch ins Deutsche zu übertragen, direkt übersetzen lässt sich das leider nicht immer alles.:

“Vögel.

Weder hat die Luft ihrerseits die richtige Versorgung mit vielen Arten von Geflügel verfehlt, wie dem grau-weißen Reiher [?], dem grau-grünen Regenpfeifer, einigen wilden Enten und Stockenten, Blässhühnern und Rotschenkeln, Meerenten [?], Graudommeln, Kormorane, eine Anzahl kleiner Vögel wie Spatzen und Fliegenschnäpper, die in letzter Zeit von den wilden Katzen vernichtet wurden, Spechten und sehr vielen Krähen, die seit der [Anlage der] Plantage getötet wurden, der Rest floh oder wird selten gesehen, außer an den unbewohntesten Plätzen, von wo aus beobachtet wird, dass sie ihren Flug gegen Sonnenuntergang antreten und ihren Kurs in Richtung Nordwesten richten, was viele Vermutungen zulässt, dass es einige weitere Inseln gibt, die nicht weit von diesem Weg entfernt sind. Manchmal werden auch Falken gesehen & Jar-Falken [?],Fischadler, ein Vogel wie ein großer Falke, aber weil sie selten kommen, werden sie nur für Besucher gehalten; vor allem aber verdienen diese beiden Arten von Vögeln Beachtung und Respekt, die eine für die Melodie seiner Stimme, die andere für sein Wirken, genannt [werden sie] Cahow, und Eier-Vogel, die am Ersten des Mai, einem stets beobachteten Tag, einen unendlichen Vorrat an Eiern, fast groß wie Hühner[eier], an bestimmte kleinen Sandküsten legen, besonders auf Coopers Island [seit den 1940ern künstlich mit St David’s Island verbunden]; und obwohl Männer unter ihnen sitzen, wenn sich an einem Morgen Hunderte versammelt haben, so bleiben sie doch unter ihnen, bis sie sich noch viele mehr versammelt haben: Sie setzen dies bis Mittsommer fort, und so zahm und angstlos, Du musst sie mit der Hand von ihren Eiern schieben, dann sind sie so schwach vom Legen, dass sie es nicht schaffen sie auszubrüten & [die Menschen] nehmen unendlich viele ihrer Jungen zum Essen, die sehr gutes Fleisch sind.”

***

Viele der hier aufgezählten Vögel lassen sich identifizieren: der ‘grau-weiße Reiher’ ist vermutlich der Kanada-Reiher (Ardea herodias L.), bei den Enten, Stockenten und Meerenten handelt es sich ziemlich wahrscheinlich um verschiedene Wintergäste, wie sie auch heute noch auftreten, die Blässhühner dürften Amerikanische Blässhühner (Fulica americana Gmelin) sein, die Kormorane sind sicher Ohrenscharben (Phalacrocorax auritus (Lesson)); bei den ‘Fliegenschnäppern’ handelt es sich mit einiger Sicherheit um Bermuda-Weißaugenvireos (Vireo griseus ssp. bermudianus Bangs & Bradlee), die einzige noch existierende endemische Vogelform der Inseln.

Einige, wie der ‘grau-grüne Regenpfeifer’ oder der ‘Rotschenkel’ lassen sich nicht wirklich identifizieren (zumindest aber handelt es sich bei letzterem mit ziemlicher Sicherheit nicht um den eigentlichen Rotschenkel (Tringa totanus (L.))); auch die Falken lassen sich nicht eindeutig identifizieren, da einige Arten immer mal wieder als Zugvögel auf den Bermudas auftauchen.

Mindestens drei der hier augezählten Vögel existieren heute nicht mehr, die ‘Graudommeln’, welche ziemlich sicher Bermuda-Krabbenreiher (Nyctanassa carcinocatactes Olson & Wingate) waren, die ‘Spatzen’, die wohl Bermuda-Grundrötel (Pipilo naufragum Olson & Wingate) waren und die Spechte, die wiederum Bermuda-Goldspechte (Colaptes oceanicus Olson) gewesen sein dürften.

All diese Arten wurden ausschließlich anhand von Knochenfunden beschrieben und zwar 2006, 2006 und 2013. [2][3][4]

***

Das größte Rätsel sind die hier erwähnten sehr vielen Krähen, denn davon gibt es auf den Inseln auch heute noch sehr viele, und zwar Amerikanerkrähen (Corvus brachyrhynchos Brehm), diese gehen jedoch nachgewiesenermaßen auf zwei Vögel zurück, die 1838 als Stubenvögel auf die Inseln gebracht worden waren.

Das bedeutet, dass es auf den Bermudas einst auch eine einheimische Krähenart gegeben haben muss, und dass diese obendrein auch noch sehr zahlreich gewesen sein muss.

Diese Form wurde offenbar von den ersten Siedlern ausgerottet, die die Krähen als Landwirtschaftsschädlinge betrachteten – scheinbar wiederholt sich die Geschichte nun, denn auch die heutzutage auf den Inseln lebenden Amerikanerkrähen werden als Schädlinge angesehen und verfolgt.

*********************

Referenzen:

[1] John Smith: The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles: with the Names of the Adventurers, Planters, and Governours from their first beginning, An: 1584. to this present 1624. With the Procedings of Those Severall Colonies and the Accidents that befell them in all their Journyes and Discoveries. Also the Maps and Descriptions of all those Countryes, their Commodities, people, Government, Customes, and Religion yet knowne. Divided into Sixe Bookes. By Captaine Iohn Smith, sometymes Governour in those Countryes & Admirall of New England. London: printed by I. D. and I. H. for Michael Sparkes 1624

[2] Storrs L. Olson; D. B. Wingate: A New Species of Night-heron (Ardeidae: Nyctanassa) from Quaternary Deposits on Bermuda. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 119(2): 326-337. 2006

[3] Storrs L. Olson; David B. Wingate: A new species of towhee (Aves: Emberizidae: Pipilo) from Quaternary deposits on Bermuda. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 125(1): 85–96. 2012

[4] Storrs L. Olson: Fossil woodpeckers from Bermuda with the description of a new species of Colaptes (Aves: Picidae). Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 126(1): 17–24. 2013

*********************

bearbeitet: 05.11.2020

Endlich, endlich beschrieben!

Das dazugehörige Fossil ist schon seit etlichen Jahren bekannt und wurde ursprünglich als Angehöriger der ausgestorbenen Familie Salmilidae aus der Ordnung der Seriemaartigen (Cariamaformes) betrachtet.

Des Weiteren konnte man oft lesen, dass es sich um einen flugunfähigen Vogel mit winzigen Stummelflügeln gehandelt haben muss, schließlich kann man diese Flügelchen ja im Foto ganz gut erkennen … nun, nein, kann man eben nicht, was man hier sieht sind einfach nur etwas ‘unglücklich’ gewachsene Federn; schaut man genau hin findet sich aber nicht die Spur irgendeines Flügelknochens!

Tatsächlich sind die Vordergliedmaßen des Tieres nach dem Tod bzw. während der Verwesung vollständig abhanden gekommen; sämtliche noch vorhandenen restlichen Teile weisen auf einen normal flugfähigen Vogel hin, er wird also zu Lebzeiten ganz normal ausgebildete Flügel besessen haben..

***

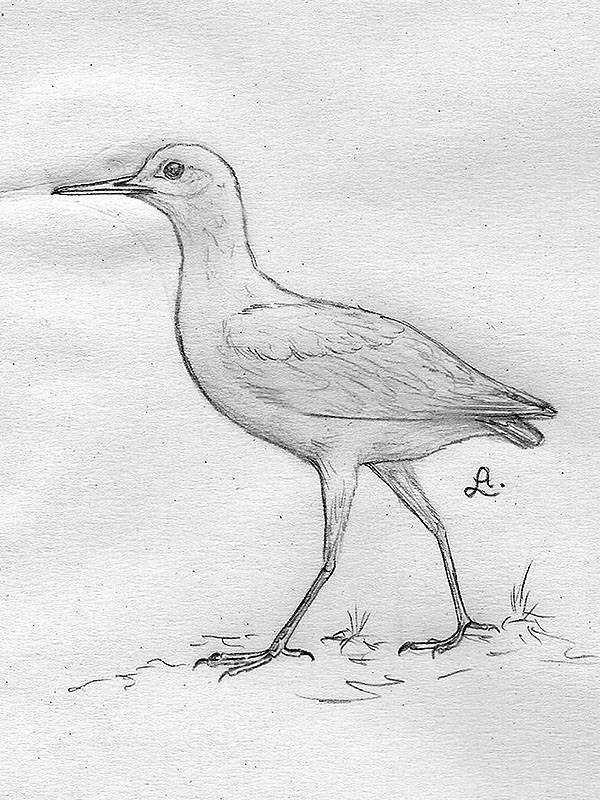

Nahmavis grandei, so heißt der Vogel nun, ist ein sehr ursprünglicher Vertreter der Regenpfeiferfamilie (Charadriiformes).

*********************

Referenzen:

[1] Lance Grande: The Lost World of Fossil Lake: Snapshots from Deep Time. University of Chicago Press 2013

[2] Grace Musser; Julia A. Clarke: An exceptionally preserved specimen from the Green River Formation elucidates complex phenotypic evolution in Gruiformes and Charadriiformes. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 8:559929. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2020.559929. 2020

*********************

*********************

bearbeitet: 26.10.2020

“Two species of Kingfishers were common on Bora-Bora (Halcyon veneratus and Todiramphus tutus), ….“

and

“HALCYON VENERATUS. (Ruru.)

This species is fairly common, especially on the island of Bora-Bora.

TODIRAMPHUS TUTUS.

Common throughout the Tahiti group.” [2]

***

These two rather cursory marginal notes from 1907 are an indication of the former existence of a bird species that no longer exists today and of which (almost) no trace can be found today.

***

The Society Islands are one of the very few places where two kingfisher species coexist, at least on the islands of Mo’orea and Tahiti in the eastern part of the archipelago; here you will find the widespread Chattering Kingfisher (Todiramphus tutus (Gmelin)), which occurs throughout the archipelago, as well as the Tahiti Kingfisher (Todiramphus veneratus (Gmelin)) and Moorea Kingfisher (Todiramphus youngi Sharpe), both restricted to a single island each.

However, the two references to the island of Bora Bora indicate that this was apparently also the case on other of the islands.

In fact, the mysterious kingfisher is not only known from small marginal notes but from at least two specimens that were collected at the beginning of the 19th century, one of which apparently still exists. This sole surviving specimen was examined in 2008 and compared to the Tahiti- and Moorea Kingfisher.

The authors concluded that this is an incompletely colored juvenile of the Tahitian species, but also note some differences, including a much shorter beak and some differences in plumage pattern, and conclude that it may also be an extinct subspecies. [3]

The species has also been depicted at least once (see below). [1]

***

Between Bora Bora in the northwestern part of the archipelago and Mo’orea and Tahiti in the eastern part are four other islands, namely Huahine, Mai’ao, Ra’iatea and Taha’a, each of which, at least today, is inhabited only by the Chattering Kingfisher.

If the island of Bora Bora was indeed once home to two species of kingfishers, then this bird must not have been a subspecies of the Tahitian Kingfisher, but a separate species; and, the other islands between Bora Bora and Mo’orea and Tahiti must most likely also have harbored now extinct and unknown distinct species.

***

In my humble opinion, however, the location of Bora Bora is simply an error, and the two birds collected there are more likely to be from the island of Tahiti. … but who knows ….

*********************

*********************

References:

[1] M. L. I. Duperrey: Voyage autour du monde: Exécuté par Ordre du Roi, Sur la Corvette de Sa Majesté, La Coquille, pendant les années 1822, 1823, 1824, et 1825, par M. L. I. Duperrey; Zoologie, par Mm. Lesson et Garnot. Paris: Arthus Bertrand 1828

[2] S. B. Wilson: Notes on birds of Tahiti and the Society group. Ibis Ser. 9(1): 373-379. 1907

[3] Claire Voisin; Jean-François Voisin: List of type specimens of birds in the collections of the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle (Paris, France). 18. Coraciiformes. Journal of the National Museum (Prague), Natural History Series 177(1): 1-25. 2008

[4] Justin J. F. J. Jansen & Roland E. van der Vliet: The chequered history of the Chattering Kingfisher Todiramphus on Tahiti: I: type specimens. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club 135(2): 108-120. 2015

[5] Justin J. F. J. Jansen & Roland E. van der Vliet: The chequered history of the Chattering Kingfisher Todiramphus on Tahiti: II: review of status. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club 135(2): 121-130. 2015

[6] Michael Lee & David T. Holyoak: The chequered history of Chattering Kingfisher Todiramphus tutus on Tahiti: a response. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club 137(3): 211-217. 2017

[7] Roland E. van der Vliet & Justin J. F. J. Jansen: Reply to Lee & Holyoak: how definite are 20th-cetury reports of Chattering Kingfisher Todiramphus tutus from Tahiti? Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club 137(3): 218-225. 2017

*********************

edited: 06.07.2023

*******************

bearbeitet: 18.10.2020

Mit dem Ende der Kreidezeit starben sämtliche so genannten Nichtvogeldinosaurier (was für ein Wortungetüm) aus, also alles was man landläufig als Dinosaurier bezeichnet aber eben auch sämtliche Vögel, die nicht der einzigen heute noch existierenden Gruppe der Vögel, den Neornithes, zugeordnet werden können.

… oder doch nicht?

***

Qinornis paleocenica ist anhand einiger Reste aus dem unteren oder mittleren Paläozän (vor etwa 61 Millionen Jahren) bekannt, die von einem einzelnen Individuum stammen: ein nahezu vollständiger linker Tibiotarsus, Teile des rechten Tibiotarsus sowie ein nahezu vollständiger rechter Tarsometatarsus mit fast allen Zehenknochen. [1]

Diese fossilen Knochen weisen einige Merkmale auf, die man bei heutigen Vögeln so nicht mehr findet, wohl aber bei einigen aus der Kreidezeit; vor allem ist der Tarsometatarsus nicht vollständig verschmolzen, er weist noch einige Riefen auf, wie man sie heutzutage nur noch bei juvenilen, nicht ausgewachsenen Vögeln findet, nicht aber mehr bei erwachsenen.

Laut einiger Experten für fossile Vögel handelt es sich bei dem Fossil aber durchaus um einen ausgewachsenen Vogel, und Qinornis paleocenica mag einer der allerletzten Vertreter einer der vielen kreidezeitlichen Vogelformen sein, die man zwar der Klade Ornithurae zuordnen kann, zu der auch die Neornithes gehören, die aber trotzdem außerhalb der Neornithes stehen. [2]

*********************

*********************

Referenzen:

[1] X. Xue: Qinornis paleocenica – a Paleocene bird discovered in China. Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg 181: 89-93. 1995

[2] Gerald Mayr: The birds from the Paleocene fissure filling of Walbeck (Germany). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 27(2): 394-408. 2007

*********************

bearbeitet: 01.09.2020

P. H. Bahr in the year 1912 quotes a Dr. B. Glanvill Corney, at that time Chief Medical Officer in the Fiji Islands.:

“There is, or was until eight or ten years ago, a bird in the interior and northern coast of Vitilevu called the ‘Sasa’; described as having speckled plumage and running along the ground among reeds, cane-brakes, and undergrowth. … The Sasa did not fly, and seems to have been a mound-builder. I once met with some dogs in a remote mountain village that the natives had specially trained to hunt the Sasa, which they described as Koli dankata sasa, i. e. Sasa-catching dogs; but I never succeeded in seeing a Sasa, nor did my friend Mr. Frank R. S. Baxendale, who, as Assistant Resident Commissioner in the hill districts, lived for more than a year in the Sasa country. His successor, Mr. Georgius Wright, however, had several living specimens in his possession for some time, and told me that he considered they were Megapodes of the same or of an allied species to those met with in the island of Ninafou [Niuafo’ou] (Boscawen Island) and in Samoa. Some natives linkened them to Guinea-fowl, but said they were not so large as the latter, and that they laid a single egg. Between the years 1876 and 1905 they were still comparatively common and well known in the locality mentioned (where there are only a very few Europeans).” [1]

***

What follows is an account by Rollo H. Beck, an American ornithologist, who quotes some notes that he received by a Mr. G. T. Barker on June 5, 1925, during a stay on the island of Viti Levu, Fiji.:

“Saca Megapode

On the Tova Estate (Viti Levu Bay) one day, as I was riding toward the Wainibaka River, I heard a zooming noise on the rocks at my right. I dismounted to ascertain, if possible, what it was, as the place which had no trees, ws such an unusual one for a pigeon. The note, too, was different, having a more vibrant tone.

Grawling twenty feet along a runway but keeping myself hidden I came upon an abandoned clearing covered with short grass. The bird was about tne yards away. It ws slightly smaller than an English game rooster, had an aggressive head with yellow beak, and a stumpy tail. The coloring which was the same on the head as on the body was a mixed yellow, approaching red, and dingy black.

The bird continued its calling for a few minutes, and was answered from the far end of the clearing. Suddenly it took alarm, and as it flew out of the clearing I saw that under the rudimentary wings there were no yellow feathers. The wings had no long feathers made a whirring sound when the birds flew. I also noticed that its legs were stout, of yellow color, and that the foot had three toes. On questioning the natives, I was told that about sixty years ago there was a great area of grass country in that part, owing probably to a denser population, and also to the fact that the people were more industrious. At that time they used to hunt the bird with dogs and would secure up to fifty in a day. Even up to the coming of the mongoose, hese birds were still hunted, but owing to the spreading of the reeds over the country the catch became small.

The birds nested, generally, under the shelter of the dead leaves of the tree fern, never out in the open, and the birds used to take turns sitting on the nest. The natives described the eggs as being white, quite round, generally one, but on rare occasions, two in a nest. They used to hunt for the eggs, and when all hands were out, as many as a hundred a day would be secured. The eggs were hatched under hens in the village, but the saca always went back to the grass and would not remain in the town.

About two years after I had seen the bird, a dependable native who had hunted the birds in his youth, told me that he had seen a pair about two miles away from The place where I had observed them. Twenty was the largest number that had been observed in one flock.

The natives said that the flesh of the saca was dark, and always lean. Its wings seem to have been of some use for the bird is called in that part “the bird that lands on eight hillocks before being cought.”

The annual rainfall in that region averages ninety inches.” [2]

In my humble opinion this whole description, except for the nesting behaviour, sounds a lot like the description of a species of megapode (Megapodius sp.).

“Yasaca

This bird I have never seen, but from all accounts it differs from the saca. First it was called “Nasataudrau”, literally, “in hundreds”, meaning that a flock would be of about one hundred. It was said of them hat they buried their eggs for the sun to hatch out.

Personally, I am doubtful if this bird ever existed in Fiji. I remember of asking a Sabeto Chief in the year 1890 if he had ever seen one – Sabeto, to the Segatoka River, being the region where the ordinary “saca” was most plentiful. This chief was then a man over sixty years old; now add on the thirty-five years since that time – ninety five years ago, and he had never seen yasaca. He had only heard the trdition in his youth.

I am inclined to believe that the natives of this region brought the tale whith them from the Solomon Islands, where megapodes still are found. See, “A Naturalist Amongst the Head Hunters” by Woodward. Mr. A. Barker has a copy of this book. There is a remarkable similarity of language between that part of the Solomons and Fiji, hence the tradition.” [2][4]

***

It is now well known that the Fiji Islands indeed were inhabited by at least two species of megapode, the Consumed Scrubfowl (Megapodius alimentum Steadman) and the Viti Levu Megapodius (Megapodius amissus Worthy). [3]

It is not really known when exactly these species disappeared; the abovementioned accounts, however, show that at least one of the species survived well into quite modern times.

*********************

References:

[1] P. H. Bahr: On a Journey to the Fiji Islands, with Notes on the present Status of their Avifauna, made during a Year’s Stay in the Group, 1910-1911. The Ibis 9(6): 282-313. 1912

[2] Whitney South Sea Expedition of the American Museum of Natural History. Extracts from the journal of Rollo H. Beck. Vol. 2, Dec. 1923 – Aug. 1925

[3] T. H. Worthy: The fossil megapodes (Aves: Megapodiidae) of Fiji with descriptions of a new genus and two new species. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 30(4): 337-364. 2000

[4] Danke Hr. Antonius, für den Hinweis, damit liegen Sie natürlich vollkommen richtig! 🙂

*********************

edited: 31.01.2022

The Polynesian Ground-Dove (Pampusana erythroptera (Gmelin)) and the Friendly Ground-Dove (Pampusana stairi (Gray)) are mentioned in several enumerations of birds that are thought to inhabit the Gilbert Islands in the Micronesian part of Kiribati.

So, I did a little search to find out something more ….:

The first thing I found was that D. H. R. Spennemann and H. Benjamin name these two species as inhabitants of the Marshall Islands, which apparently is an error since they use A. B. Amerson’s account as their source, in which they are clearly named as inhabiting the Gilbert – but not the Marshall Islands. [2][4].

This is the abovementioned account by A. B. Amerson Jr..:

“Gallicolumba erythroptera* Ground Dove

Status — Introduced breeder in the Gilbert Islands.

Marshall-Gilbert Distribution Records — Breeding: Gilberts – Abemama, Nonouti.

Pacific Distribution — Native to the Society and Tuamotu Islands (Baker, 1951).

*Remarks — I am using the species designation given by Child (1960), who says this species was reported to have been introduced into the Gilberts from Nauru about 1940. Pearson (1962) did not find any doves at Nauru in 1961.” [2]

The Gilbertese name of this bird is given here as bitin, more about that later.

“Gallicolumba stairi* Friendly Ground Dove

Status — Introduced, possible breeder in the Gilbert Islands.

Marshall-Gilbert Distribution Records — Gilberts – Abemama.

Pacific Distribution — Present only at Fiji, Tonga, and Samoa Islands (Peters, 1934)

*Remarks — I am using the species designation given by Child (1960) who says this species was probably introduced from Fiji.” [2]

Here the author states “Child (1960)” as his source, so let’s see where that leads me to.

I could trace all accounts back to the following one, which appears to be the first that mentiones these two dove species, it is from a Peter Child who worked for about one year as an radio operator in the Coastwatching Organisation during WWII and who visited nearly all the islands in the ‘colony’ within a time of three years from 1953 to 1956.

He was an amateur bird-watcher, as he called himself, but his accounts are in fact reliable, in my opinion.

Here they are.:

“24. Gallicolumba erythroptera: Ground Dove.

Lupe palangi. Bitin (Taobe)

While Ducula is a native in the Ellice, being referred to in many old songs and legends, the ground doves are undoubtedly recent introductions of the present century, probably mainly from Fiji. At Abemama they are reported to have been introduced from Nauru about 20 years ago [ca. 1936 because this account was originally puplished in 1956], and have multiplied considerably so that there is now a fair number in a wild state. A few pairs have also been taken from Abemama to some other Gilbert Islands as pets, but in most of the Colony they are unknown. A pair taken to Nanouti had four offspring, and in June two females had nests about ten feet of the ground in an old deserted house; the nests were of grass and stra and built inside old boxes; each contained two eggs, oval in shape and creamy-white in colour. At Abemama they are said to nest in coconut crowns, often high above the ground. They feed mainly on the ground; when disturbed they fly up into the palms and their call, a soft “coo”, may then be heard.

The colouring is typically darkish greys and white; the head, neck, back and upper breats are grey with a purplish and greenish sheen or irridescence; the secondary wing feathers are mainly dark grey and the primaries and tail feathers mainly white; the abdomen is white, often speckled with grey, and he under tail-coverts white. The short bill is dark grey with a small whitish operculum at the base; the legs and feet are coral red, or purplish red. Some birds have less white than others, and hardly any two are exactly alike.” [1]

The name Bitin apparently is the local variation of the English word pigeon, while the name Taobeundoubtedly is the local variation of the German word Taube which means nothing but dove/pigeon; both these names suggest that the birds were imported from somewhere else.

The name Lupe palangi is the Tuvaluan name given to this bird, it can be translated as foreign pigeon (!).

It also appears to me that he did see this species with his own eyes.

He goes on with the second dove species.:

“25. Gallicolumba stairii. Friendly Ground Dove.

There are few individuals in a semi-wild state at Abemama, probably of this species, and probably introduced from Fiji where it is common. The habits are similar to those of G. erythroptera, and there is no distinction in vernacular names of the two species.

The colouring is mainly brown with a little white on the wings and lower breast; the upperparts have a greenish sheen in some lights. The bill is dark and the feet deep red or purplish red.“

*********************

All in all it appears to me that both, the Polynesian- as well as the Friendly Ground Doves, indeed had been introduced sometimes during the middle 1930s, during WWII to at least the Abemama atoll, it appears not to be known by whom, and it also appears not to be known if they still exist there.

Interesting is the statement that at least one of them had been brought from Nauru, where no groud dove species is known to have existed – and if one has existed it might rather have been a distinct, endemic one, but not the Polynesian Ground Dove.

Maybe someone with an interest in birds will be able to make a visit to the Abemama atoll some day and clarify these questions.

*********************

References:

[1] P. Child: Birds of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands colony. Atoll Research Bulletin 74:1-38. 1960

[2] A. B. Amerson Jr.: Ornithology of the Marshall and Gilbert Islands. Atoll Research Bulletin 127: 1-348. 1969

[3] Robert P. Owen: A checklist of the birds of Micronesia. Micronesica 13(1): 65-81. 1977

[4] Dirk H. R. Spennemann; Hemley Benjamin: Notes on the Avifauna of Ebon Atoll, Republic of the Marshall Islands. Historic Preservation Office 1992

*********************

edited: 30.07.2020

When you’re dealing with extirpated/extinct birds, you will sooner or later come across species that raise more questions than others.

Such a species is the Mangareva-yes-what-actually?:

“Lanius gambieranus Lesson, 1844, Écho du Monde Savant, p. 232 (cf. Ménegaux, p. 180). IlesGambier. Type perdu depuis longtemps.

Connue seulement par la description du spécimen qui était autrefois dans la collection du Docteur Abeillé de Bordeaux. Lesson précise qu’une peinture fut préparée par M. Charles Thélot de Rochefort, mais nous n’avons pas retrouvé cette peinture, ni d’ailleurs le spécimen.

[RÉPARTITION ET STATUT]. – Selon Lesson, le spécimen décrit provenait des îles Gambier. Ces îles furent visitées par plusieurs expéditions maritimes françaises avant 1840, et le spécimen fut probablement rapporté par le frère de Lesson, le Docteur Adolphe Lesson, qui voyagea durant quatre années dans les mers du Sud comme «Chirurgien» à bord d’un bateau. Le spécimen était autrefois dans la collection Lesson à Rochefort.

Les seules autres mentions de passereaux aux îles Gambier sont données par Garrett qui trouva des fauvettes durant la seconde moitié du xix* siècle (Wiglesworth, 1891b) et par Buck (1938) qui note KOMAKO – «Reed Warbler». Signalons aussi qu’une fauvette fut observée sur l’îlot Tepapuri en 1971 (Thibault, 1973b). Ce dernier oiseau, blanchâtre dessus et brun dessous, devait être un erratique de la forme habitant les atolls au nord des Gambier, A. caffer ravus. Deux spécimens M.N.H.N ont été considerés comme des oiseaux pouvant provenir des îles Gambier (Lacan et Mougin, 1974b), mais il s’agit vraisemblabIement d’une forme éteinte d’ A. luscinia provenant de Micronésie (Holyoak et Thibault, 1978b). L’expédition Whitney ne trouva pas de fauvette en visitant les îles Gambier, en dépit de nombreuses recherches en 1922 (Beck et Quayle, ms).

[DISCUSSION], – L’oiseau décrit par Lesson ne correspond à aucune forme de spécimens connus. Il est douteux qu’il s’agisse d’une pie-grièche (Laniidae), comme l’avait pensé Lesson. Il est également peu probable que se soit un siffleur (Pachycephala), comme certains auteurs l’ont suggéré (Lacan et Mougin, 1974b; Thibault, 1973b).

La taille, la forme et la coloration font plutôt penser à une fauvette, voisine des formes habitant les îles Cook. Cette hypothèse serait d’autant plus vraisemblable qu’il serait étonnant que des îles volcaniques de la taille des Gambier n’aient pas eu de fauvettes. Sans doute, Lesson avait déjà décrit en 1820 la Fauvette de Tahiti comme appartenant au genre Tatare, mais il n’est pas étonnant qu’il n’ait pas établi de relation entre cette fauvette et l’oiseau des Gambier, en raison de leurs différences morphologiques importantes.

De nombreuses interrogations subsistent au sujet de cet oiseau et il n’est pas évident qu’il ait été véritablement collecté aux Gambier, bien que les autres descriptions de Lesson ne présentent pas d erreurs de localité. “

translation:

“Lanius gambieranus Lesson, 1844, Écho du Monde Savant, p. 232 (cf. Ménegaux, p. 180). Gambier Islands. Type long lost.

Known only by the description of the specimen that was once in the collection of Doctor Abeillé de Bordeaux. Lesson specifies that a painting was prepared by Mr. Charles Thélot de Rochefort, but we have not found this painting, nor indeed the specimen.

[DIVISION AND STATUS]. – According to Lesson, the described specimen came from the Gambier Islands. These islands were visited by several French maritime expeditions before 1840, and the specimen was probably brought back by Lesson’s brother, Doctor Adolphe Lesson, who traveled for four years in the South Seas as a “surgeon” aboard a boat. The specimen was formerly in the Lesson collection in Rochefort.

The only other records of passerines in the Gambier Islands are given by Garrett who found warblers in the second half of the nineteenth century (Wiglesworth, 1891b) and by Buck (1938) who noted KOMAKO – “Reed Warbler”. It should also be noted that a warbler was observed on Tepapuri islet in 1971 (Thibault, 1973b). This last bird, whitish above and brown below [shouldn’t it be vice versa?], must have been an erratic of the form inhabiting the atolls north of the Gambiers, A. caffer ravus. Two M.N.H.N specimens have been considered as birds that may have originated from the Gambier Islands (Lacan and Mougin, 1974b), but they are probably an extinct form of A. luscinia from Micronesia (Holyoak and Thibault, 1978b). [they are now known to indeed be specimens of a species formerly inhabiting the island of Mangareva] The Whitney expedition did not find a warbler when visiting the Gambier Islands, despite extensive research in 1922 (Beck and Quayle, ms).

[DISCUSSION], – The bird described by Lesson does not correspond to any form of known specimens. It is doubtful that it is a shrike (Laniidae), as Lesson had thought. It is also unlikely to be a whistler (Pachycephala), as some authors have suggested (Lacan and Mougin, 1974b; Thibault, 1973b).

The size, shape and coloring are more like a warbler, similar to the forms found in the Cook Islands. This assumption would be all the more likely since it would be astonishing if volcanic islands the size of Gambier did not have warblers. No doubt Lesson had already described the Tahitian Warbler in 1820 as belonging to the genus Tatare, but it is not surprising that he did not establish a relationship between this warbler and the Gambier bird, because of their significant morphological differences.

Many questions remain about this bird and it is not obvious that it was really collected in Gambier, although the other descriptions of Lesson do not present errors of locality.” [3]

Today, most ornithologists think that the description fits best with the extinct Mangarevan Reed-Warbler, a bird that is known to have indeed existed. Yet, there are in fact two surviving specimens of this species, Acrocephalus astrolabii Holyoak & Thibault, which, however, are still often referred to as having been collected somewhere in Micronesia, an assumption that is now obsoleted. [4]

However, the reed-warbler was much larger than 14 cm, and it lacks the yellow underside that our enigmatic bird is said to have had; but let’s just take a look on the original description, it is in French and reads as follows:

„Cette pie-grièche est fort voisine du Lanius tabuensis de Latham. Comme elle, on la trouve dans le mer du Sud, et c’est aux îles Gambier qu’elle vit.

Cette espèce a les formes courtes et trapues. Elle mesure 14 centimètres. Ses ailes sont presque aussi longues que laqueue; son bec est peu crochu, bien que denté; il est noiràtre ainsi que les tarses; tout le plumage en dessus, les ailes et la queue sont d’un brun olivàtre uniforme; le devant du cou, à partir du menton jusqu’au haut de la poitrine, est olivàtre foncé; tout le dessous du corps, depuis le haut du thorax jusqu’aux couvertures inférieures, est du jaune le plus vif et le plus égal; les plumes tibiales sont brunes, mais cerclées d’une sorte de jarretiere jaune à d’articulation le dedans des ailes est varié de jaune et de blanc, ce qui forme un rebord étroit, blanc dessous du fouet de l’aile; la queue est légèrement échancrée, et le sommet des rectrices présente un point jaune.” [1]

Here is my translation:

“This shrike is very close to Lanius tabuensis [Aplonis tabuensis (Gmelin)] of Latham. Like this, it is found in the South Sea, and it lives in the Gambier Islands.

This species has a short, squat form. It measures 14 centimeters. Its wings are almost as long as the tail; the beak is slightly hooked, but dentate; it is black as well as the tarsi; all the plumage above, the wings and the tail are uniformly olive brown; the front of the neck, from the chin to the top of the breast, is dark olive; the whole lower part of the body, from the top of the thorax to the lower coverts, is the liveliest and most even yellow; the tibial feathers are brown, but circled in a sort of yellow, hinged garter, the underside of the wings is varied with yellow and white, forming a narrow, white rim beneath the whip of the wing; the tail is slightly forked, and the top of the rectrices are dotted yellow.”

You see, the species was described as a shrike (Laniidae) and as being very closely related to Lanius tabuensis.

Well, shrikes, of course, do not exist in Oceania at all, and Lanius tabuensis is called Aplonis tabuensis today and is a starling (Sturnidae), the South Sea Starling. You must know that in the 19th century still no one really had any idea of biogeography, and the same applies to the relationships between the different bird species.

Not a shrike, but what about a starling – Aplonis gambieranus?

Hm, according to the description rather not, the size (14 cm) seems a bit too small (my gut feeling), and the colors do not fit to any other Polynesian starling.

Not a starling, but what about a robin – Eopsaltria gambierana?

“EOPSALTRIA GAMBIERANA.

Lanius gambieranus, Less. Echo de M. S. 1844, p. 232.

Eopsaltria gambierana, Hartl. Wiegm. Arch. für Naturg. 1852, p. 133.

Low or Paumotu Islands (Gambier’s Islands or Mangarewa).” [2]

This genus does not occur in Polynesia, but the closely related genus Petroica does indeed (both genera belong to the family Petroicidae), however, both genera, in my eyes, can be excluded for biogeographic reasons.

Not a robin, but what about a whistler – Pachycephala gambierana?

The bird was for some time also thought to may have been a whistler and the genus Pachycephala indeed is occuring in Polynesia, yet only in the western part, namely in Fiji, Samoa and Tonga but not further east, so, no.

Not a whistler, but what about a monarch – Monarcha gambierana?